Under the Republic

of the Philippines

1900

1946 Philippine Independence: A Separate People in a New Nation

New Administration, Same Old Policies

1948 Kamlun Uprising

The Bandung Conference in 1955

The 1961 Congress Bill for Sulu Independence

The 1968 Mindanao Independence Movement (MIM)

1946 Philippine Independence: A Separate People in a New Nation

1946 Philippine Independence: A Separate People in a New Nation

On July 04, 1946, the American government illegally annexed Sulu and Mindanao when it granted the Philippine independence despite the series of protests and warnings of many Muslim leaders. This illegal annexation became the root of the contemporary armed struggle that culminated in an armed conflict in 1972.

With their commitment to maintain the integrity of the Philippine state that had been ceded by Spain in 1898, the American government illegally annexed Sulu and Mindanao when they granted Philippine Independence on July 04, 1946. Despite protests against this inclusion and the warnings of future bloodshed by many Muslim leaders, American administrators could not also ignore the pressure of Manila Christian politicians who were against any plan of reducing the country. Besides, like the Spaniards and their Christianized natives, American administrators view Muslims as backward and unprogressive people who needed association with the more economically developed Christian-dominated Philippine state in order to share with them the benefits of the modern, more “civilized” world.

Thus, while the Christian Filipinos became independent, the Muslims saw another colonial rule, this time, the Manila Christian politicians. The freedom they fought to keep for centuries was handed over to their traditional enemies whose ways of thinking reflect much of their colonial masters. Indeed, those Manila Christian politicians just carried on foreign colonial policies and programs that were not only compatible and sensitive with the values and beliefs of the Muslims but alienated them in their own homeland.

Sources:

Gowing, Peter G. 1979. Muslim Filipino: Heritage and Horizon. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Gross, Max L. 2007. A Muslim Archipelago: Islam and Politics in Southeast Asia. Washington, DC: NDIC Press.

Majul, Cesar Adib. 1985. The Contemporary Muslim Movement in the Philippines. Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press.

Read More

New Administration, Same Old Policies

New Administration, Same Old Policies

One of the colonial policies that Christian Filipino politicians pursued was the sending of Christian settlers from Luzon and the Visayas which slowly marginalized the Muslims in Mindanao. This policy caused unrest and strife which later forced the Muslims to once again fight the Manila colonial government.

After Sulu and Mindanao were illegally annexed by the American government to the newly established Philippine state in 1946, the welfare of the Muslims was now in the hands of the Manila Christian politicians. While many Muslim leaders found some political positions both local and national in this new government, most Muslims did not share this sense of national unity.

The implementation of Western Christian-based national laws was often in conflict with their Adat (customary) and Islamic laws especially those pertaining to personal and family relations that the Muslims have been accustomed to. The public school system did not differ much from those of the American occupation and Commonwealth government. The same curriculum was implemented for all children regardless of religion and cultural differences. Christian Filipino educators still carried the idea of assimilating the Muslims into a larger national community while the Muslims have a different history and distinct culture. Thus, Muslim parents thought that this school curriculum was no different from that of the Americans which was to alienate their children from Islam.

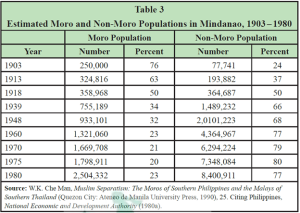

The continuous influx of Christian settlers slowly outnumbered the Muslims in Mindanao. In 1960, Muslim population was 1,321,060 while the Christians was already 4,364, 967 constituting 77% of the total population. “This led many Muslims to conclude that there was a deliberate government scheme either to disperse them or to ensure that they remain a permanent minority in their own territories. They noted with frustration, if not envy, that the areas where the Christians had settled now had better roads and more effective irrigation projects, civic centers, and schools in comparison with their own backward facilities. So, they believed that they were the victims of government discrimination and of neglect by their own leaders. In turn, Muslim leaders blamed all the ills on the so-called Christian government in Manila.”

Sources:

Majul, Cesar Adib. 1985. The Contemporary Muslim Movement in the Philippines. Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press.

Che Man, W K. 1990. Muslim Separatism: The Moros of Southern Philippines and the Malays of Southern Thailand. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Gutierrez, E and S Borras. 2004. The Moro Conflict: Landlessness and Misdirected State Policies. Washington DC: East-West Center.

Read More

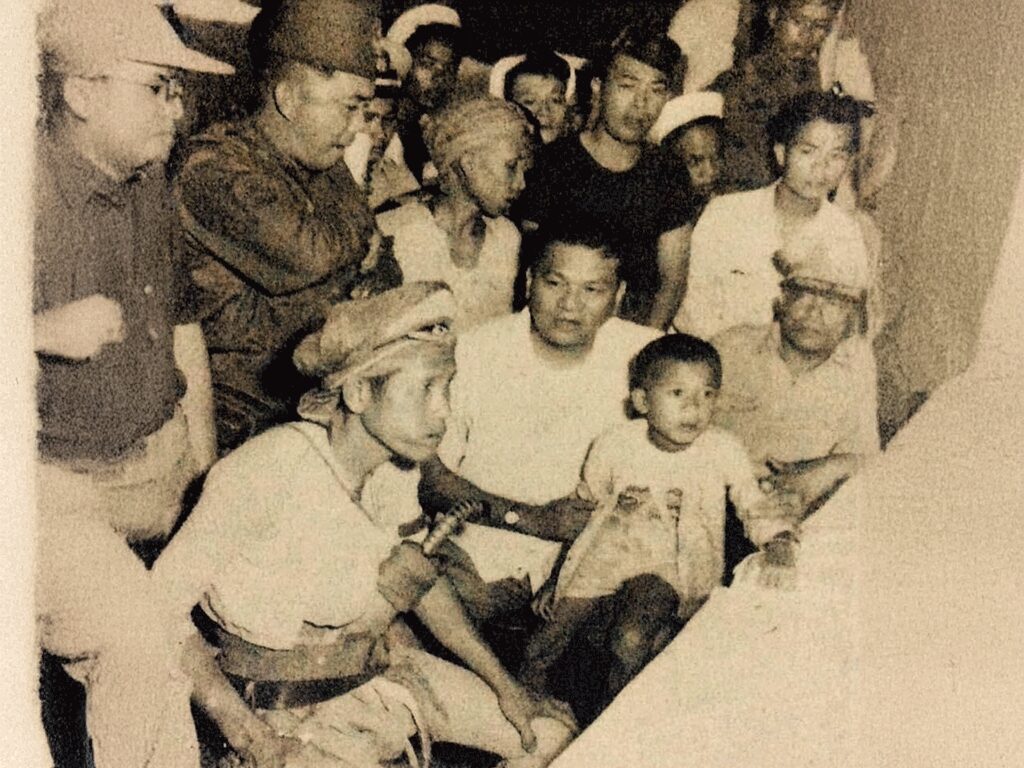

1948 Kamlun Uprising

1948 Kamlun Uprising

In 1948, Kamlun Haji led an uprising against the government due to the continuous marginalization of the Muslim population and the government’s land registration policy. His rebellion, which caused heavy casualties and economic bankruptcy on the side of the government, resulted in the creation of the Commission on National Integration (CNI) and the establishment of Mindanao State University (MSU) to provide better education for Muslims, as ways to accelerate their integration into the larger Philippine society.

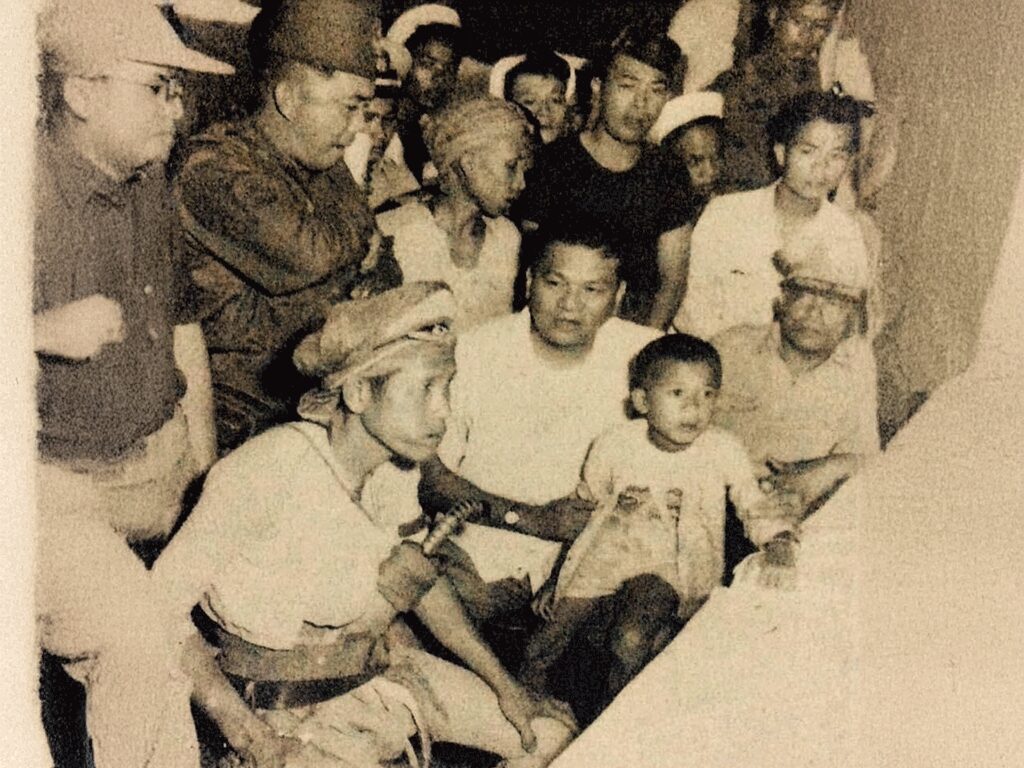

Kamlun Haji was a famous local hero among the Tausug in Sulu who fought against the Japanese during Japan’s invasion from 1941-1945. Fueled by agrarian intrigues, socioeconomic issues, political threats, and the growing marginalization of the Muslim population by the Philippine government that favored and extended more benefits to Christians, Kamlun revolted against the government and this lasted eight years. Despite his forces being relatively small, Kamlun’s impact was profound because it dismembered the famous Nenita (Korean War veteran) Unit. His uprising became the second largest threat to the Philippines next to the Hukbalahap, which compelled Ramon Magsaysay, who was then the defense secretary, to negotiate his surrender.

Despite four years of extensive government campaigns involving 5,000 ground troops and substantial financial costs of around 185 million pesos, the government never captured him. In the end, Kamlun’s advancing age led him to finally surrender in 1955, marking the conclusion of one of the most formidable rebellions in Philippine history. He was imprisoned in Muntinlupa only to be given pardon by President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. in 1968 through the mediation of Nur Misuari who became later on the chairman of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF). Kamlun’s life was portrayed by Ramon Revilla in the film Kamlun in 1981.

Kamlun’s uprising prompted the government to create a congressional committee in 1954 to study and make recommendations on the Mindanao and Sulu problems. The committee headed by a Muslim congressman (later senator), Domocao Alonto, brought out the issue of land disputes, stated that Muslims did not feel part of the nation, and made various recommendations. However, only the creation of the Commission on National Integration (CNI) was fully carried out. And despite its many purposes, such as the acceleration of the Muslims’ progress in terms of the political and economic systems, and their integration into the social system of the country, the commission instead focused on the granting of scholarships to Muslims and other cultural minority groups.

In September 1961, the Mindanao State University in Marawi was also established, whose one of the functions is “to help accelerate the program of the integration among the peoples of Southern Philippines, particularly the Muslims and other cultural minorities.” Still, education and integration remain to be the priority solution of the government in addressing the Muslims’ concerns, a solution that did not prove to be appropriate in the succeeding years.

Sources:

Tan, Samuel K. 2007. “Unity and Disunity in the Muslim Struggle.” UP Diliman Asian Studies Journal. Page 4. 92. VOLUME 43:1. https://www.asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-11-3-1973/tan-unity%20disunity%20muslim%20struggle.pdf

Stern, Tom. 2012. An Authorized Bibliography of Nur Misuari. Anvil Publishing Inc., Manila.

Mawallil, Amir. 2916, “What makes a hero?” ABS-CBN News. August 29, 2016. https://news.abs-cbn.com/opinions/08/29/16/opinion-what-makes-a-hero

“TANKS HUNT FOR FILIPINO; Kamlon, Notorious Bandit, Is Target of All-out Campaign”. The New York Times. 15 July 1952.

Read More

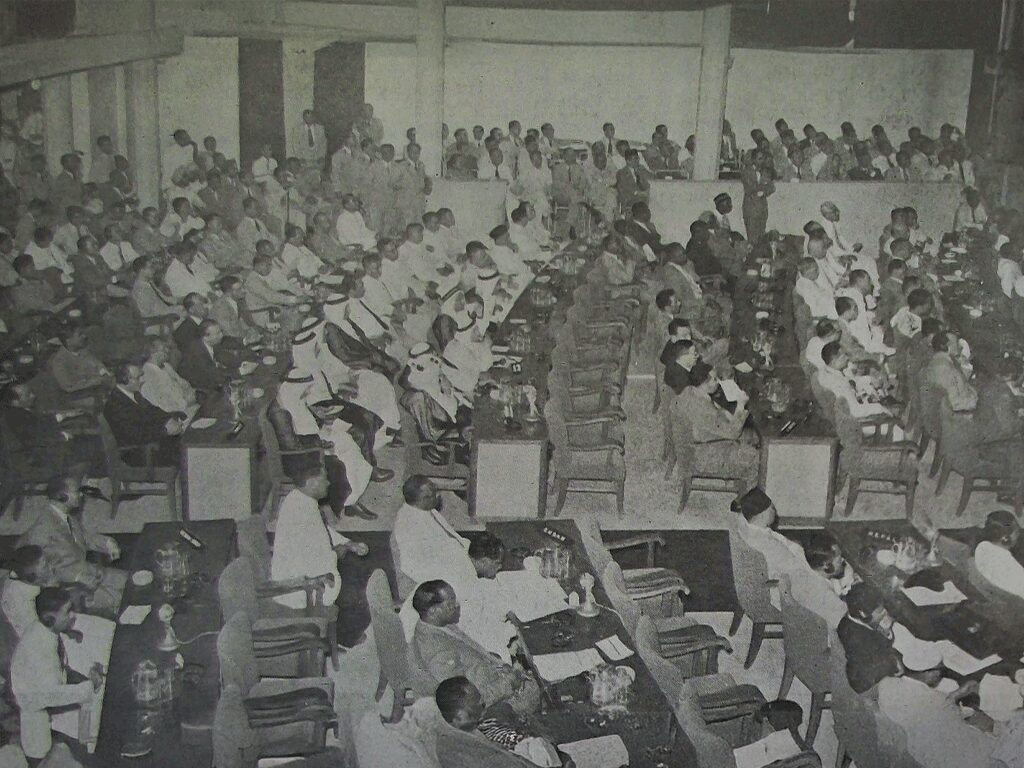

The Bandung Conference in 1955

Bandung Conference in 1955

The 1955 Bandung Conference attended by late Senator Domocao Alonto from Lanao reconnected Muslims in the Philippines with the global Muslim ummah (community). It gave birth to Islam’s revival in Mindanao and Sulu and inspired the sense of nationalism of Muslim scholars who studied Islam in Egypt. Ustadz Salamat Hashim and Ustadz Abdulbaki Abubakar, were among those scholars.

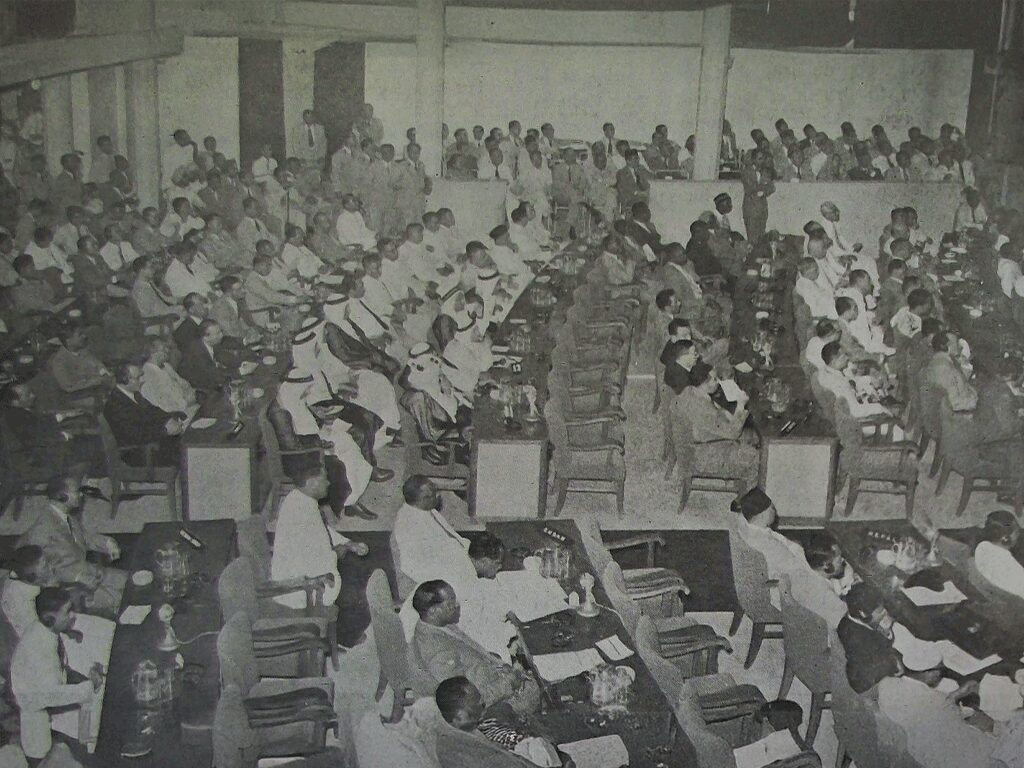

On April 24, 1955, a conference, which was attended by 29 countries from Asia and Africa, was held in Bandung, Indonesia. This conference was a response to the growing influence of communism in Asia and Western imperialism in Africa. It aimed at forging a new international order that was neither communist nor capitalist.

The late Senator Domocao Alonto managed to express the plight of the Muslims in the Philippines which most of the delegates were not aware. As a result, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser offered scholarships for Muslims in the Philippines to study in his country. The conference was followed by the visit of the Egyptian Minister of Awqaf (Endowments) Sheikh Ahmad Hassan el-Bakhouri to Mindanao. Islamic conferences in Lanao and Sulu were also organized. By 1958, the first batch of scholars arrived in Cairo, Egypt.

At that time, Cairo was the center of political activism in the Middle East. The Pan-Islamic movement of Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser which sought to unify the Arab world was very prominent during that time. This condition shaped many foreign students to become leaders of resistance movements in their respective countries. This includes Ustadz Salamat Hashim from Maguindanao and Ustadz Abdulbaki Abubakar from Sulu. Ustadz Salamat became vice chairman of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and later founder of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), while Ustadz Abubakar was appointed Foreign Affairs secretary general.

Sources:

Lucman, Dato Norodin Alonto. 2000. Moro Archives: A History of Armed Conflict in Mindanao and East Asia. Quezon City: FLC Press, Inc.

Tan See Seng and Amitav Acharya. 2008. Bandung Revisited: The Legacy of the 1955 Asian-African Conference for International Order. Singapore: NUS Press.

Read More

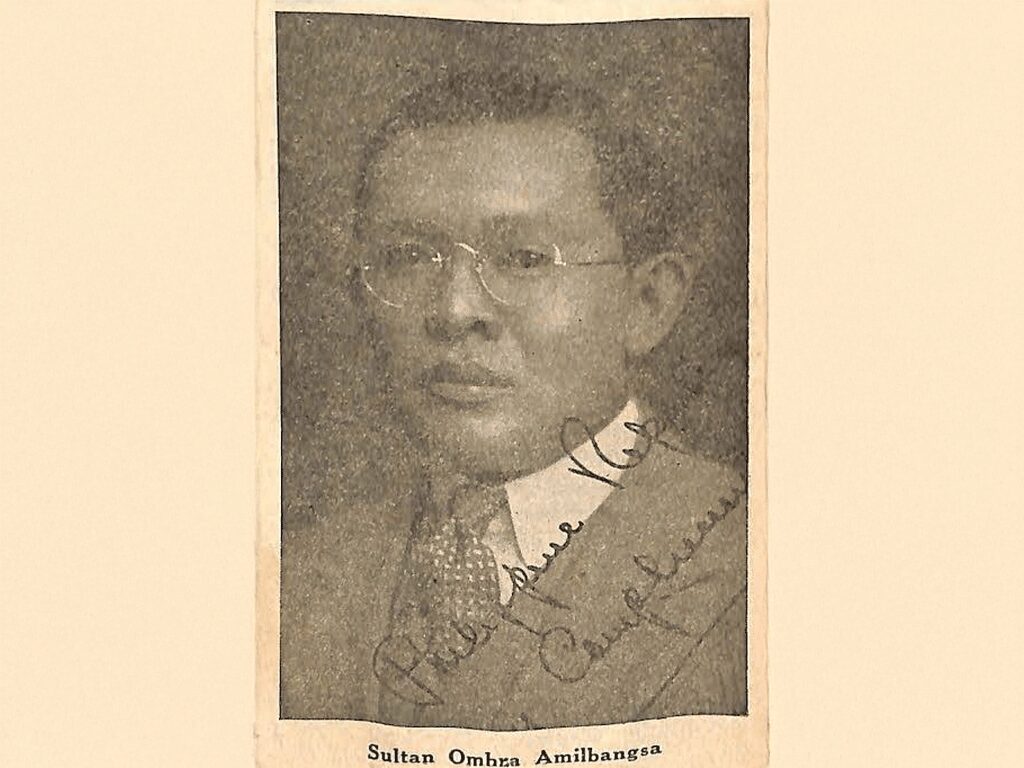

The 1961 Congress Bill for Sulu Independence

The 1961 Congress Bill for Sulu Independence

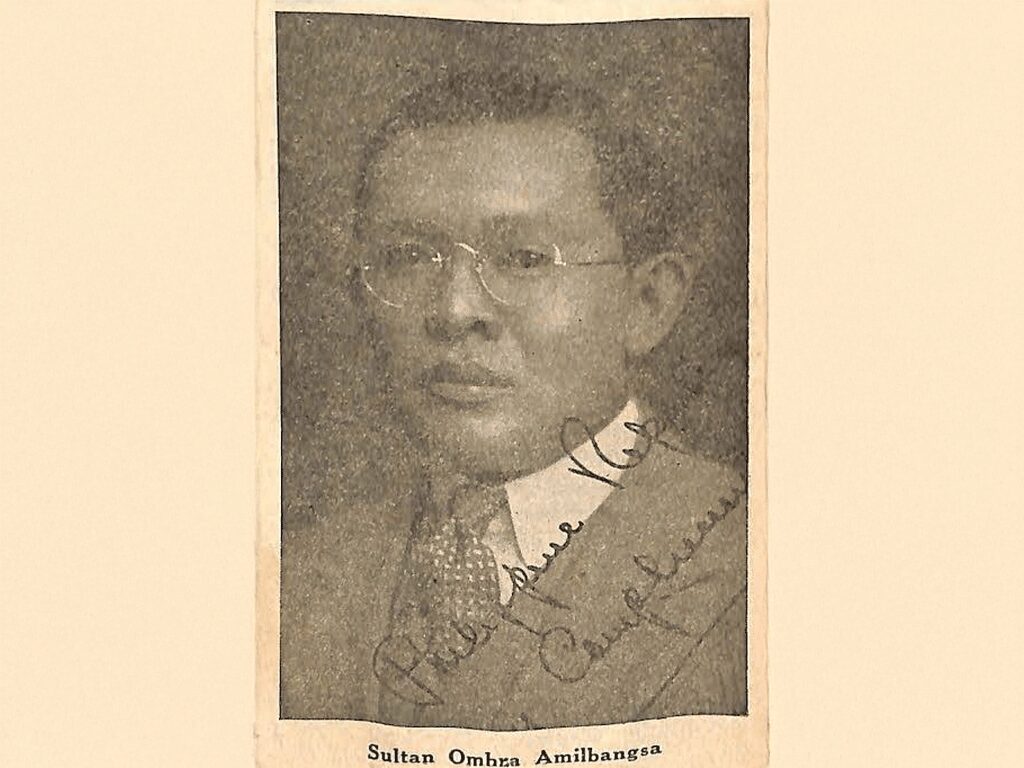

In 1961, Sulu Congressman Datu Ombra Amilbangsa introduced House Bill 5862 calling for the granting of Sulu Independence. The bill fell on deaf ears in the House of Congress.

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2693760987616990&set=a.2346452985681127

Datu Ombra Amilbangsa was married to Dayang-Dayang Hadji Piandao, the niece of Sulu Sultan Hadji Jamalul Kiram. He was a member of the Philippine National Assembly from 1935 to 1938 representing Sulu and was later appointed governor of Sulu by President Manuel L. Quezon. Then from 1941 to 1946, he was Sulu’s lone congressman in the Philippine Commonwealth’s House of Representatives; and the Philippine House of Representatives from 1946 to 1961.

Following the revolt of Kamlun Haji, he filed a bill in the House of Congress that sought independence for Sulu Province. Although the media publicized the bill and drew comments from historians and those interested in Muslim affairs, nothing came out of it in Congress.

Sources: Majul, Cesar Adib. 1985. The Contemporary Muslim Movement in the Philippines. Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press.

The Sulu Cultural and Historical Society Facebook Page. https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=2693760987616990&set=a.2346452985681127

Read More

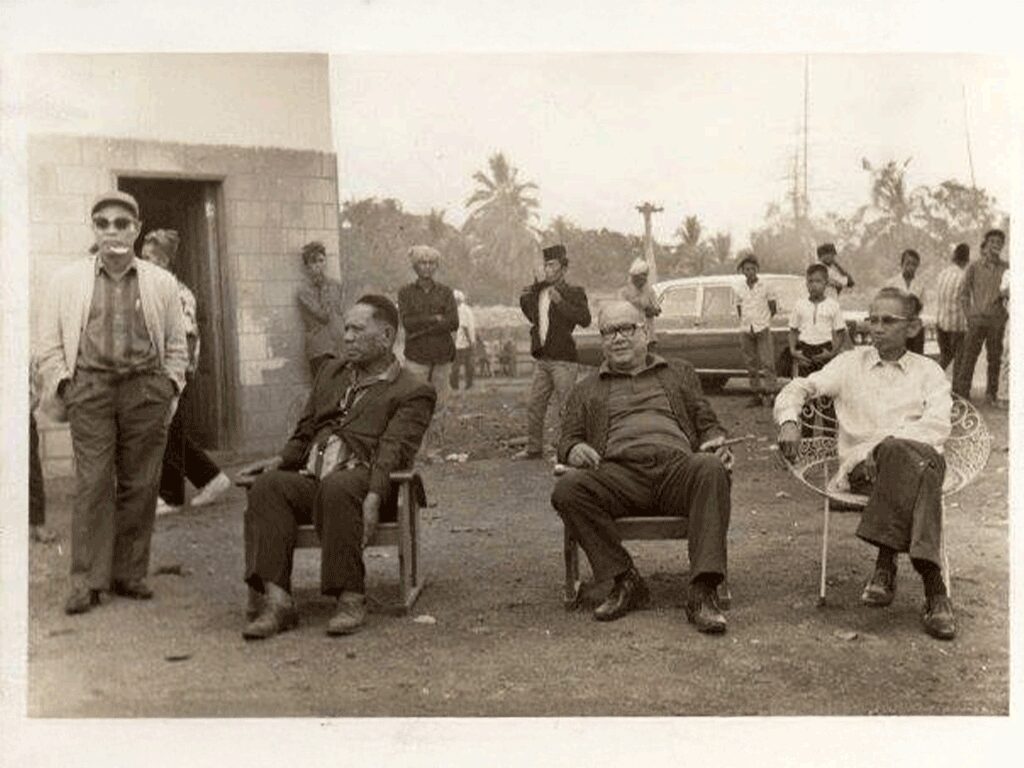

The 1968 Mindanao Independence Movement (MIM)

The 1968 Mindanao Independence Movement (MIM)

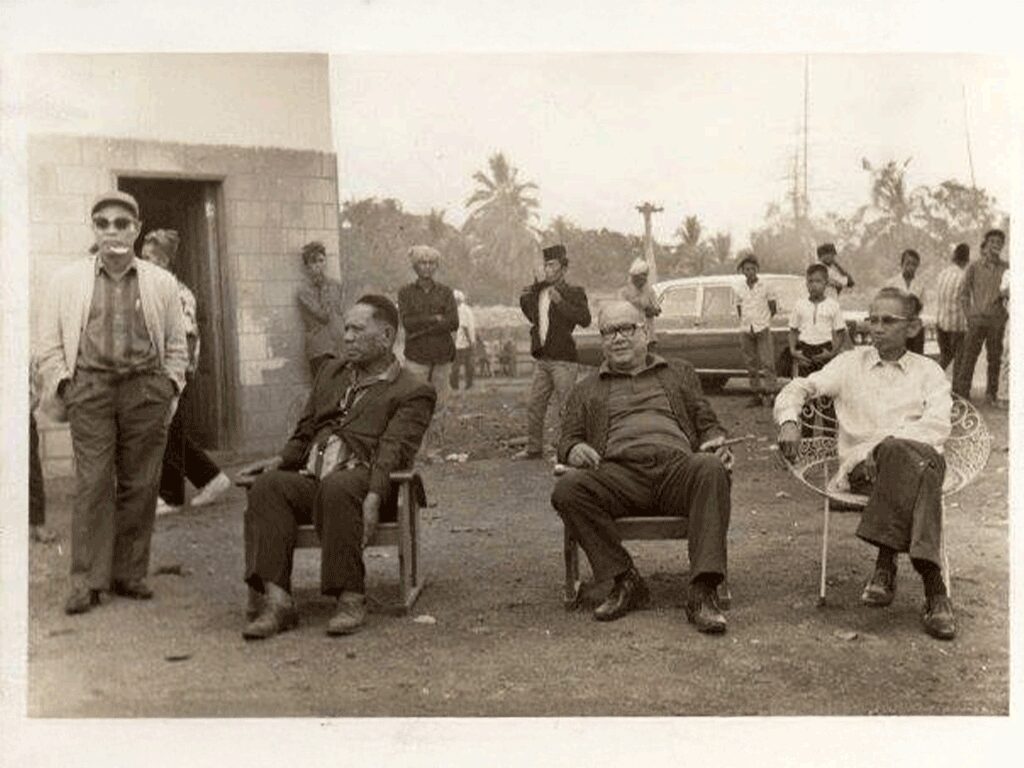

Following the March 18, 1968 Jabidah Massacre in Bataan of Muslims who were training to invade Sabah, Malaysia, former Cotabato Governor Datu Udtug Matalam, on May 01, 1968, announced the establishment of the Muslim Independence Movement (MIM). Although short-lived, the movement revived memories of Muslim freedom and independence. It also compelled ambitious Christian politicians and businessmen in Mindanao to form their armed bands to protect themselves.

https://www.facebook.com/1408575796122947/photos/a.1446416879005505/1460768380903688/?type=3

Muslim-Christian relationship in Mindanao started to become tense when the government’s liberalization of land ownership restrictions, combined with monopolistic laws on commodity export, allowed several politically linked Christian families to accumulate vast plantation holdings. Aside from losing their lands to Christian settlers, the Muslims began to be deprived of employment and economic opportunities.

These tensions were accelerated by an incident in Corregidor, Bataan, on March 18, 1968, when 23 Muslims from Sulu who demanded to go home because of their delayed allowances were executed by elements of the Philippine Army who recruited them for military training to allegedly take back Sabah, Malaysia. Driven by this incident, his loss in the political arena, and the continuous marginalization of the Muslims in Mindanao, Datu Udtug Matalam established the Muslim Independence Movement on May 01, 1968. He later changed it to Mindanao Independence Movement to include the Christian settlers since Datu Udtug was a former governor of Cotabato and a proponent of Muslim-Christian harmony in Mindanao. However, the MIM was disbanded when Datu Udtug was appointed by President Marcos Sr. as presidential adviser for Muslim Affairs when they met in Cebu in October 1968.

Despite its brief existence, MIM has attracted many admirers and revived the Muslims’ memory of their past freedom and independence. Anticipating troubles ahead, ambitious Christian politicians and businessmen brought in trained and armed people and began to form a group called Ilaga that would terrorize Muslim communities. In June 1971, they massacred more than 70 Muslims, including women and children, inside the mosque in Manili village, North Cotabato.

The criminal activities of the Ilaga were often tolerated by the Philippine Constabulary (PC). A manifesto to end killings of Muslims in Mindanao which was produced from a meeting of Muslim politicians, businessmen, young scholars, and many others in Manila was not taken seriously by the government. Traditional Muslim politicians in Lanao and Maguindanao formed the Blackshirts and Baracudas to counteract the activities of the Ilaga. Although there was no organized armed resistance against the government during this period, tensions in Mindanao were already escalating. Meanwhile, Nur Misuari and other young scholars were already in Malaysia for their military training.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar Adib. 1985. The Contemporary Muslim Movement in the Philippines. Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press.

Che Man, W K. 1990. Muslim Separatism: The Moros of Southern Philippines and the Malays of Southern Thailand. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Gutierrez, E and S Borras. 2004. The Moro Conflict: Landlessness and Misdirected State Policies. Washington DC: East-West Center.

Glang, Alunan C. 1971. Muslim Secession or Integration? Manila: Cardinal Book Store.

Luga, Alan R. 2002. “Muslim Insurgency in Mindanao, Philippines.” A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of U.S. Command Army and General Staff College. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Brown, Graham. 2015. The Long and Winding Road: The Peace Process in Mindanao, Philippines. IBIS Discussion Paper No. 6. Institute for British-Irish Studies University College Dublin.

Read More