The Rise of the Liberation Movements

and the Peace Processes

1900

Jabidah 1968, Misuari, And the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF)

The 1972 Martial Law and the All Out War in Mindanao and Sulu

1976 Tripoli Agreement

Ustadz Salamat Hashim and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

President Marcos’ Reconstruction and Reforms

1984

The Pat a Pengampong ko Ranaw

1986 - President Corazon Aquino and the Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao

The Rise of the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG)

The 1996 Final Peace Agreement

2000

Estrada’s All Out War Against MILF in 2000

The 2008 Memorandum of Agreement and on Ancestral Domain

President Aquino’s Bangsamoro Basic Law and the Crises of Peace Talks

2015 Mamasapano Incident – BBL Died with SAF 44

President Duterte’s War and Peace Efforts

The Birth of Maute-ASG Alliance and the Marawi Siege

The 2018 Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (BARMM)

2019 - 2022

Passage of the BOL Prescribed Codes in the BARMM

2021

BARMM Marks Economic Growth and Shift from Agriculture to Service-Oriented Economy

2022

BBM Unity

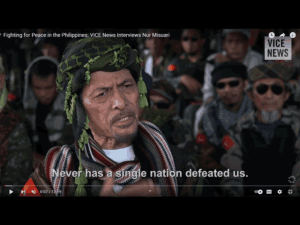

Jabidah 1968, Misuari, And the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF)

Jabidah 1968, Misuari, And the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF)

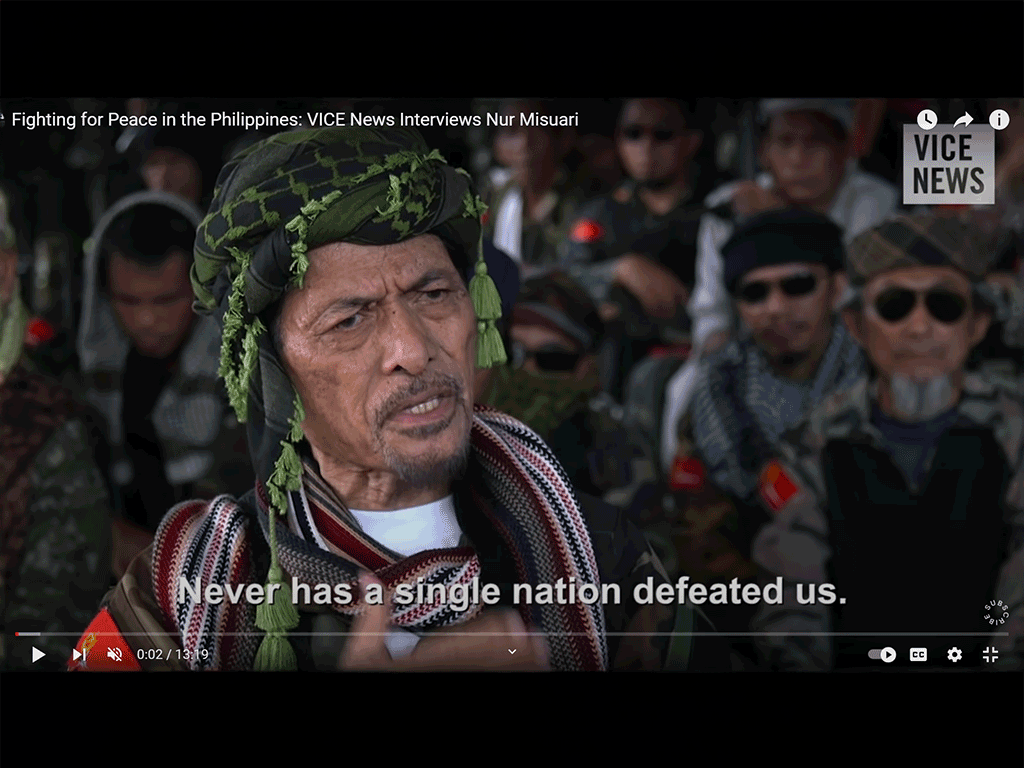

Nur Misuari was already teaching at the University of the Philippines in Diliman when he joined the protest in front of Malacañang Palace. When justice was not given to those Muslim trainees who have been massacred by the Philippine Army in Corregidor, Bataan on March 18, 1968, he left his teaching career for a military training in Malaysia and got elected chairman of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF).

Nur Misuari was born on March 3, 1939, in Tapul, Sulu. After finishing high school, he entered the University of the Philippines in Diliman in 1958 through the scholarship of the Commission on National Integration (CNI). At that time, political activism of the left was prominent in the campus. He studied political science and later law and associated with several political organizations. The first one was Bagong Asya which introduced world ideologies in the campus. Later, he became one of the founders of the Kabataang Makabayan whose chairman was Jose Maria (Joma) Sison, founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines. By the time the incident on March 18, 1968 happened, Nur Misuari was already teaching at the University of the Philippines Diliman.

The March 18 incident which became known as the Jabidah Massacre was a military secret operation called Merdeka whose aim was to allegedly take back Sabah from the Malaysian government. More than 200 Muslims from Sulu and Tawi-Tawi were recruited for a military training in Tawi-Tawi and were later transferred to Bataan. Those 23 who were massacred demanded to be sent home when all their promised allowances were delayed. Jibin Arola was wounded and managed to escape. He was saved by fishermen and was brought to the governor of Cavite who at that time was against the Marcos administration. The secret operation was then exposed by the governor’s ally, the late Senator Ninoy Aquino.

Nur Misuari, along with many young Muslim scholars, held protest outside the Malacañang Palace for several days. They were demanding justice, but the military involved were acquitted despite investigations. It was here that Misuari’s political career began. With the disintegration of the Mindanao Independence Movement (MIM) of Datu Udtug Matalam, the young Misuari left teaching, which was his first love, and joined the first batch of military training, “The 90”, arranged by the Malaysian government and the traditional leaders of Mindanao. When Martial Law was declared by President Marcos Sr., a well-organized Moro National Liberation (MNLF) with Misuari as chairman emerged as a single voice which unified the Muslim tribes and their aspirations under the name Bangsamoro, and began to challenge the government in a wide-scale military confrontation, with the battle cry “Victory or graveyard.”

https://defenders-philippine-sovereignty.blogspot.com/search/label/Operation%20Merdeka

https://chrisbonoan.blogspot.com/2015/06/jabidah.html

Sources:

Stern, Tom. 2012. An Authorized Bibliography of Nur Misuari. Anvil Publishing Inc., Manila.

Tan, Samuel K. 1977. The Filipino Muslim Armed Struggle, 1900-1972. Manila: Filipino Foundation Incorporated,

Majul, Cesar A. 1985.The Contemporary Muslim Movement in the Philippines. Berkeley: Mizan Press.

Read More

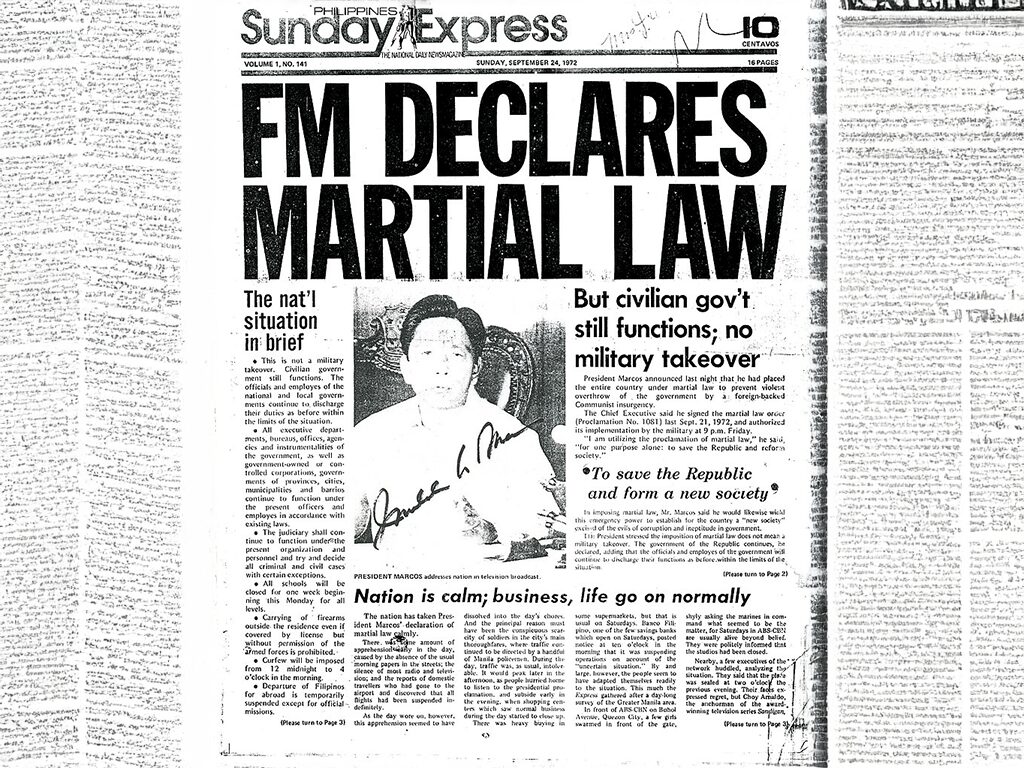

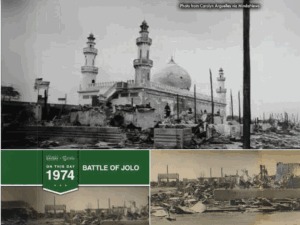

The 1972 Martial Law and the All Out War in Mindanao and Sulu

The 1972 Martial Law and the All Out War in Mindanao and Sulu

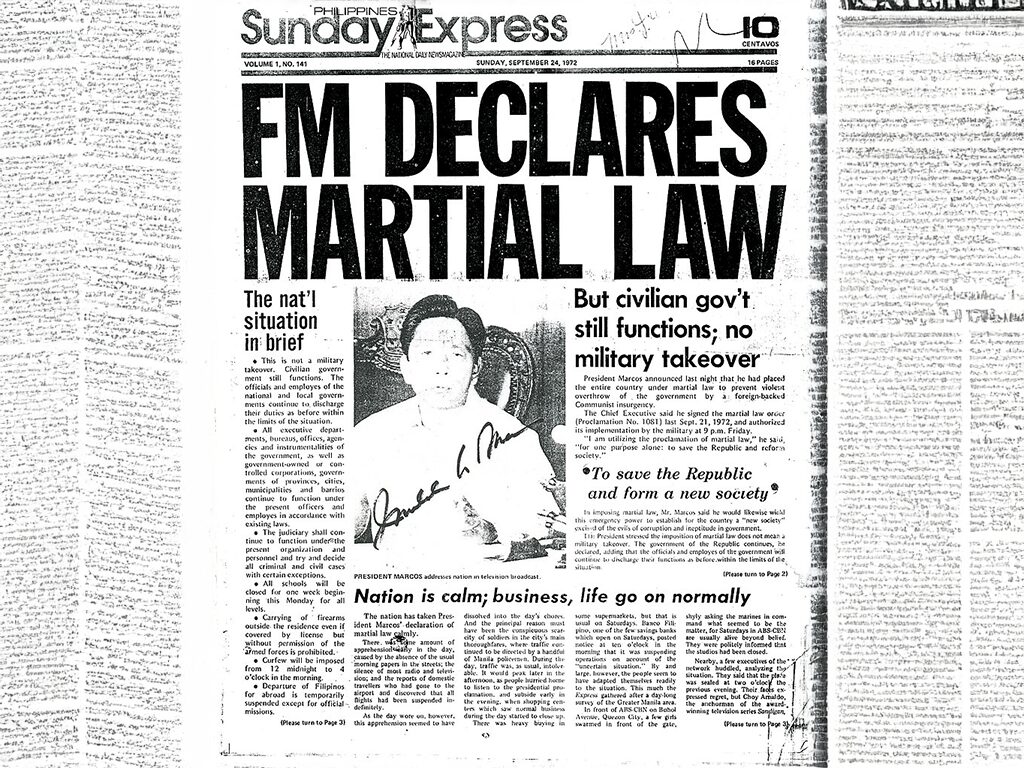

On September 21, 1972, President Ferdinand Marcos declared in the South. The Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) responded with armed resistance.

The declaration of Martial Law was immediately followed by an order to confiscate arms in Muslim Areas. This order led to the first military encounters between the MNLF and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). With their military trainings in Malaysia, the MNLF was confident in its ability to confront the AFP. And it had already been receiving arms and other resources from Libya whose President Muammar Gaddafi was convinced that Marcos was conducting genocidal campaign against the Muslims. During the early wars, reports of military victories were notably absent from newspapers, while reports of the increasing Muslim fighters with sophisticated weapons were spreading. President Marcos said, “In the late February to early March 1973, some 6,000 rebels overran much of the Cotabato Provinces. Before that, several thousand other rebels had occupied most of the Basilan Island of Zamboanga del Sur. In the province of Sulu, our troops were hanging on only to towns – the hinterland was lost to the rebels who outnumber them.” The war had cost the lives of about 120,000 people and displaced 300,000 more. On February 07, 1974, the Military had to burn almost the entire Jolo town to drive out MNLF fighters who were hiding in civilian houses. In September of the same year, about 1,500 Moro men and women were killed by military and paramilitary forces at the coastal community of Malisbong in Palimbang, Sultan Kudarat.

From 1973-1975, President Marcos deployed 70-80% of the AFP to Mindanao and Sulu. The war, however, has put his administration in bad light and started to drain Philippine economy. Iran and Saudi Arabia’s reduction of oil exports to the Philippines slowed down the military’s air operation. Moreover, the government had depleted its military material and was forced to buy these from Taiwan. As supplies dwindled and the cost of war was rising exponentially, Marcos had no choice but to negotiate with the MNLF. Fearing to be isolated from the members of the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) which was pushing to end the war, the MNLF also agreed to sign the agreement with Libya as the mediator.

Sources:

Stern, Tom. 2012. An Authorized Bibliography of Nur Misuari. Anvil Publishing Inc., Manila.

Luga, Alan R. 2002. “Muslim Insurgency in Mindanao, Philippines.” A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of U.S. Command Army and General Staff College. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Castro, Delfin. 2005. A Mindanao Story: Troubled Decades in the Eye of the Storm. Manila: Delfin Castro.

Vitug, Marites D. and Glenda M. Gloria. 2000. Under the Crescent Moon: Rebellion in Mindanao. Ateneo Center for Social Policy and Public Affairs. Teachers’ Village, Quezon City: Katipunan, Quezon City and Institute for Popular Democracy. .

Abat, Fortunato U. 1999. The Day We Nearly Lost Mindanao: The CEM-CON Story, 3rd ed. Manila: FCA Publishers.

Palembang Massacre. https://vimeo.com/235016290

Read More

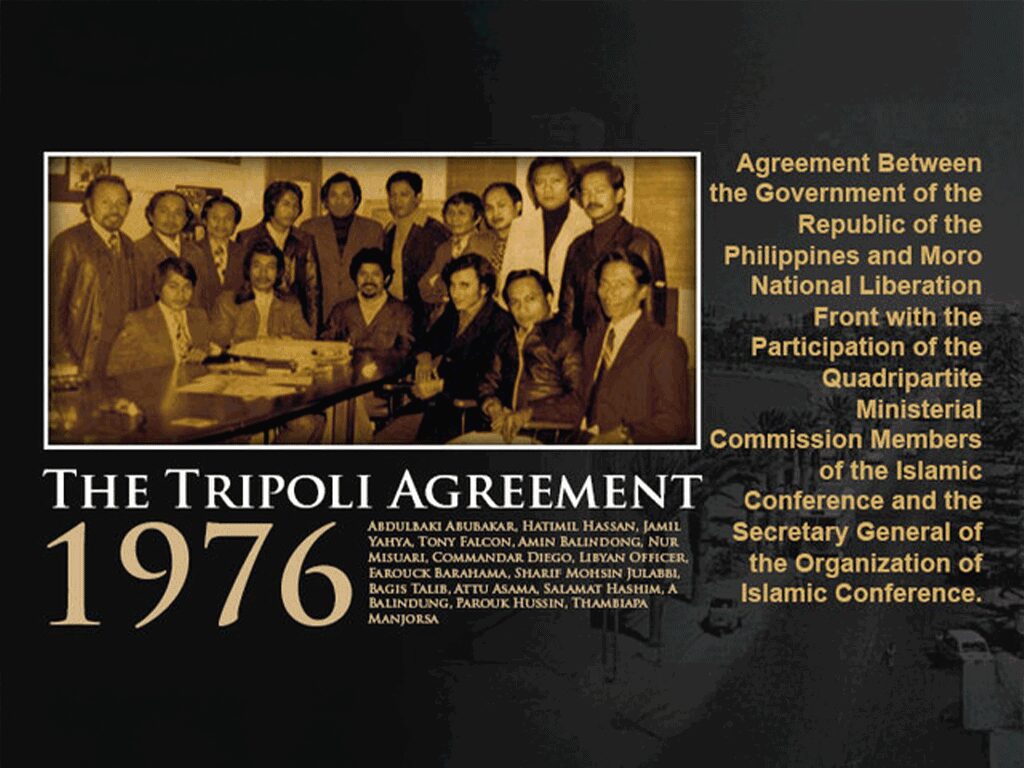

1976 Tripoli Agreement

1976 Tripoli Agreement

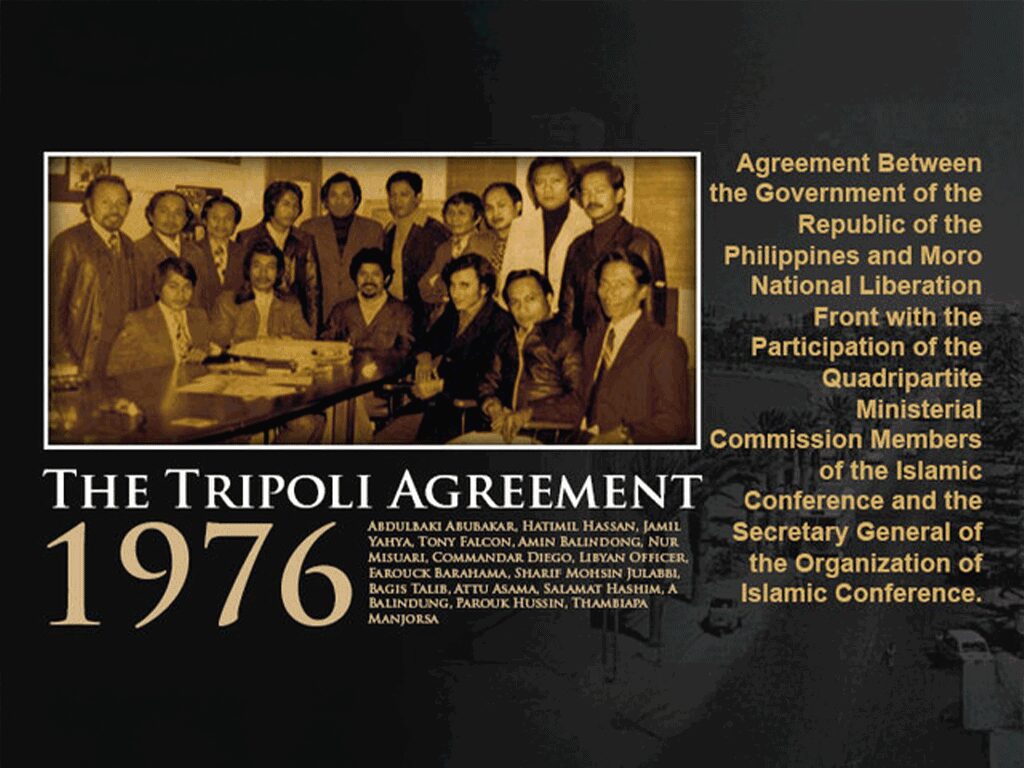

On December 23, 1976, the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) signed an agreement for autonomy in Tripoli, Libya. MNLF Vice Chairman for Foreign Relations, Ustadz Salamat Hashim left the organization and formed the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).

The Tripoli Agreement granted the MNLF autonomous regional administration over 13 provinces and 4 cities in Mindanao and Sulu that would have Islamic courts aside from the official judicial system, pursue its own economic and educational programs. One provision, however, became a source of conflict. Marcos insisted that Article 6 of the Agreement shall allow “(t)he Philippine government (to) undertake all necessary constitutional processes to implement the entire agreement.” MNLF leaders saw this as a scheme to minimize the regional organization’s territorial jurisdiction, knowing that in most of the provinces that were supposed to come under its control, non-Muslims would not support the autonomous government. Furthermore, Marcos unilaterally created two autonomous regions (9 and 12) instead of single autonomy. This resulted in the collapse of the Tripoli Agreement. Both the MNLF and the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) which granted MNLF observer status rejected this unilateral decision of splitting the autonomous region. MNLF also boycotted the plebiscite.

Unhappy with Chairman Misuari’s decision, ideology, and leadership style, Ustadz Salamat Hashim, who was then the Vice Chairman for Foreign Relations, left the organization.

Sources:

Stern, Tom. 2012. An Authorized Biography of Nur Misuari. Manila: Anvil Publishing Inc..

Iribani, Abraham. 2006.Give Peace a Chance: The Story of the GRP-MNLF Peace Talks. Mandaluyong City: Magbassa Kita Foundation,

Jubair, Salah. 1999. Bangsamoro: A Nation Under Endless Tyranny. Kuala Lumpur: IQ Marin.

Read More

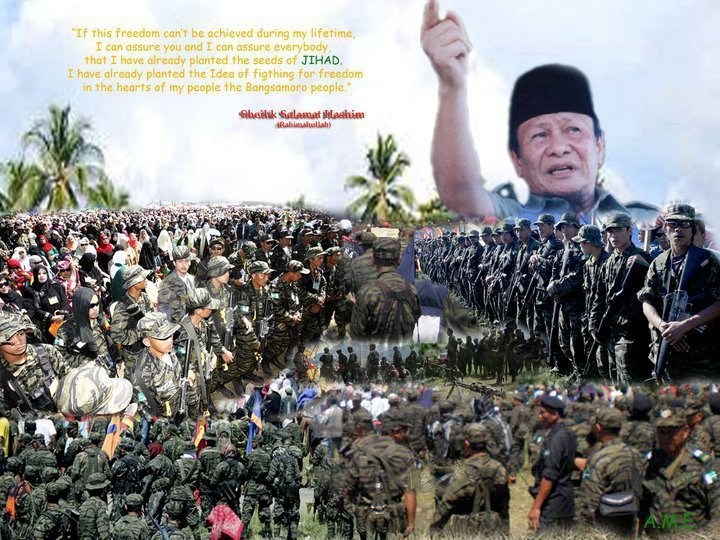

Ustadz Salamat Hashim and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

Ustadz Salamat Hashim and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

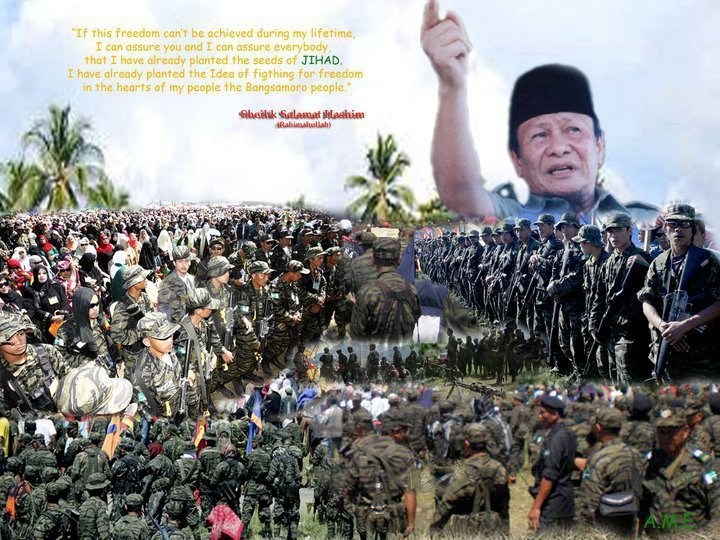

After leaving the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) during the 1976 Tripoli Agreement, Ustadz Salamat Hashim formed his Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF).

Ustadz Salamat Hashim was born on 7th July 1942 in the Municipality of Pagalungan, Maguindano. At the age of six he started formal education, finishing his elementary education in 1954 with honors and his secondary education in 1958 also with honors.

After graduating from high school, he joined a pilgrimage to Makkah (Mecca) and stayed for further study under the care of a Sheikh Jawawi. A year later, he went to Cairo to study at Al-Azhar University. He also joined a Sufi Tariqa (Islam’s spiritual order). After finishing his undergraduate in 1963, he enrolled in the same university for a master’s program specializing on the Aqidah and Philosophy. Salamat joined the Philippine Muslim Association and was elected president. Apart from this, he was also elected as secretary general of the Organization of Asian Students composed of members coming from various ASEAN countries. Later, he formed his own group composed of Muslim students coming from Southern Philippines whose aim was to organize and mobilize a Muslim revolution in the Philippines. After finishing his MA In 1969, Salamat enrolled in a PhD program in the same university, but never finished his dissertation as he went home to join the MNLF. He was appointed chairman of the Kutawato Revolutionary Committee and was elevated to the Central Committee where he became the MNLF’s Vice Chairman.

As an Alim (religious scholar), Ustadz Salamat anchored his political ideology on Tawhid (Divine Oneness) where Allah is the Supreme Ruler and Absolute Law Giver. He exhorted his followers to conduct all aspects of their lives including political, legal, economic, educational, and social systems under Allah’s Divine Law. The da’wah (propagation) sought to deepen Muslims’ understanding of Islam especially its moral conducts that were derived from the Qur’an and the examples of Prophet Muhammad. He argued that this could only fully happen under a sovereign Bangsamoro state. The Bangsamoro must therefore strive to have their independent state. Salamat’s model of independent Islamic government was federal where the Christians and Iidigenous people in Mindanao would have their own state. It further aimed to reform every home and the community in general into an Islamic home and Islamic community.

After leaving the MNLF, he organized his own group initially known as “The New Leadership.” He moved his new organization to Cairo, Egypt, and then to Lahore, Pakistan in 1980, where it engaged in diplomatic activities and formally established the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) in 1984.

Sources:

Lingga, Abhoud Syed Mansur. 1995. “The Political Thought of Salamat Hashim.” A Thesis Submitted to the Institute of Islamic Studies University of the Philippines Diliman.

Read More

President Marcos’ Reconstruction and Reforms

President Marcos’ Reconstruction and Reforms

While engaging the Moro National Liberation Front with a military campaign, President Marcos also initiated various programs and reforms to accommodate Muslim aspirations. One of these programs was the codification of Muslim Personal Laws where Muslims can adhere to their Islamic law on matters of marriage and other personal laws.

MNLF armed resistance forced President Marcos to re-evaluate Muslim grievances in the country. He realized that in order to reconstruct Philippine society, Muslim aspirations and expectations must be accommodated to make them feel as part of the larger Filipino society. Through Presidential Decree No. 264, he created the Philippine Amanah Bank with an initial capitalization of 50 Million pesos in 1973 to promote and accelerate the socioeconomic growth and development of Mindanao. He also established the Institute of Islamic Studies in the University of the Philippines Diliman in order to bridge religious and cultural gaps among Filipino Muslims and Christians.

The following year, President Marcos established the Southern Philippine Development Authorization (SPDA) to increase economic interaction between Moros and Christian Filipinos at regional borders. He also created the Presidential Task Force for the Reconstruction and Development of Mindanao to rehabilitate devastated areas. Finally in February 1977, President Marcos approved the Code of Muslim Personal Law that deals with Islamic provisions for marriage, divorce, and inheritance applicable to Muslims, and recognized all important Muslim holidays.

Toward the end of his regime, President Marcos continued to initiate programs addressing Muslim aspirations despite the collapse of the Tripoli Agreement and the 1977 ceasefire over disagreement on the extent of autonomy. In 1978, he created the Office of Muslim Affairs and Cultural Communities (OMACC) which catered to the needs of both Muslims and non-Muslims.

Then there was the Letter of Instruction dated 1984 addressed to the prime minister, members of the cabinet, and the Ministry of Education and Culture, in which President Marcos urged these offices to “optimize the development of human resources of the nation and to preserve and enhance the nation’s Islamic heritage.” In line with this letter, the agencies were directed to “formulate and adopt a program for the development of the madrasah schools, strengthen the development of programs in Islamic studies in state institutions of higher learning especially in Mindanao, including the accelerated strengthening of programs in Shariah law, and establish and strengthen programs in the teaching and learning of Arabic language.”

All these programs he initiated became the foundation of succeeding administrations’ policies and programs for the Muslims in the country.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar A. 1985. The Contemporary Muslim Movement in the Philippines. Berkeley: Mizan Press.

https://amanahbank.gov.ph/about-the-bank/history

http://www.chanrobles.com/legal3oma.htm

https://chanrobles.com/letterofinstructions/letterofinstructionsno1221.html

Read More

The Pat a Pengampong ko Ranaw

1984

The Pat a Pengampong ko Ranaw

Based on the narration of Dumarpa (1984), central to the traditional system of land ownership and possession among the Meranaw is the tradition of the Pat a Pengampong ko Ranao (the four principalities of the lake), namely, Unayan, Bayabao, Masiu and Balo-i. The four pengampongs represent the largest socio-juridical and territorial entity in Meranaw society the tradition of which Meranaw remembrances recite in every important gathering. Ideally, a pongampong is subdivided into suku (district), which in turn is partitioned into several inged (towns), which are in turn classified as pegawidan (supported)/superordinate) and pegawid (supporter/subordinate). The inged is made up of... Read More

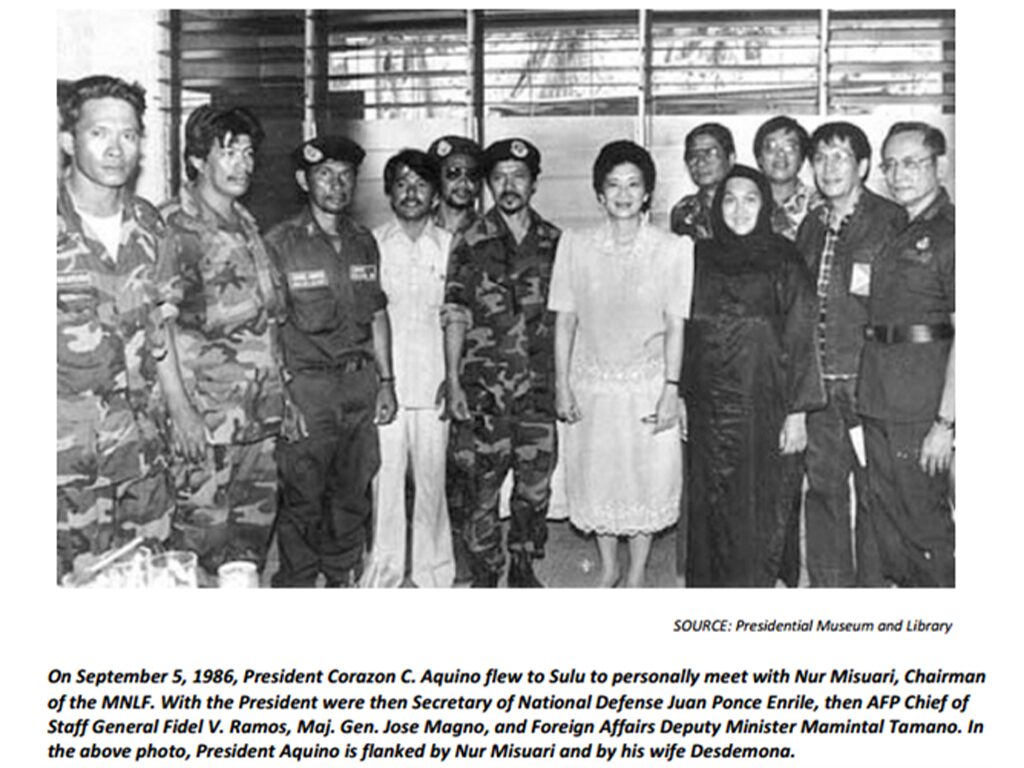

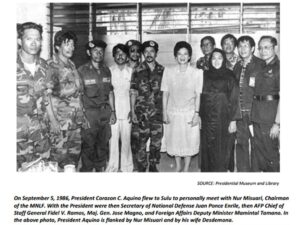

1986 - President Corazon Aquino and the Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao

1986 - President Corazon Aquino and the Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao

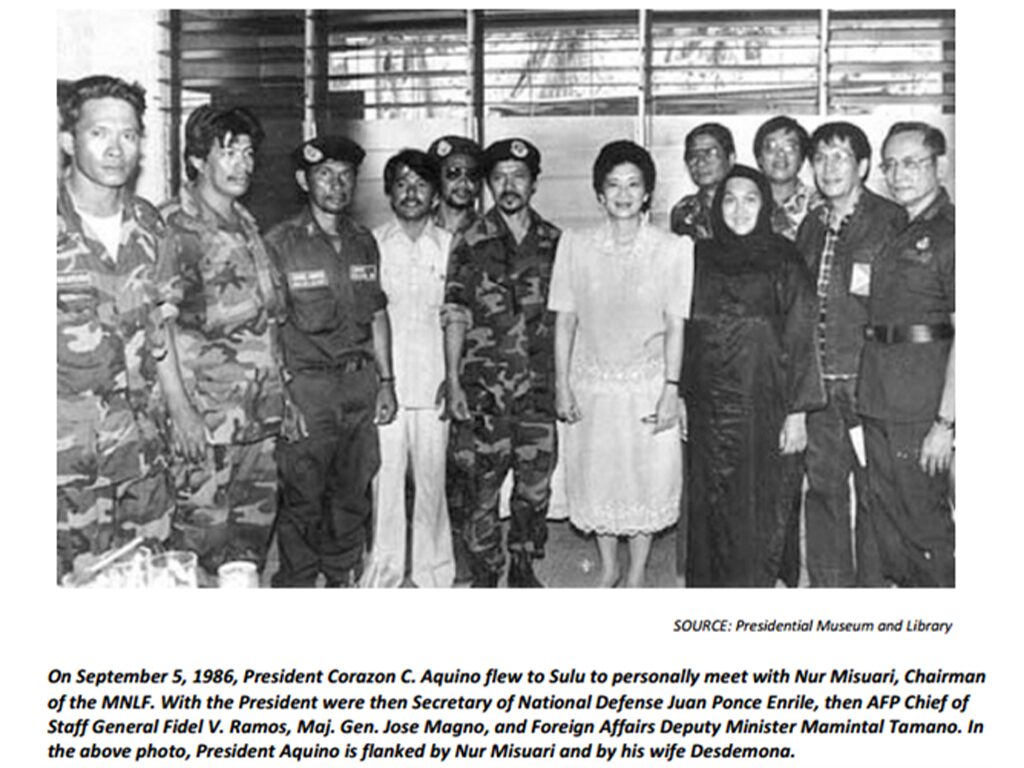

On February 25, 1986, Corazon Aquino was installed president through a People Power Revolution that ousted President Ferdinand Marcos Sr. Renewal of peace negotiation with the MNLF was one of her priorities as a fulfilment of their agreement with Chairman Misuari abroad. In September 1986, she went to Sulu to discuss the agreement with Misuari. The negotiation, however, failed on the same constitutional process which led to the rise of the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG). Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) was created.

Less than a month after President Marcos fled the country, the MILF held a press conference and a three-day prayer in Cotabato that was attended by tens of thousands of their members and supporters. It called for the new Aquino government to renew peace negotiations and to implement the Tripoli Agreement. President Aquino, however, went instead to Jolo to meet Chairman Misuari for peace negotiations. This she did despite the objections of her cabinet members. She wanted to fulfil her late husband’s (Senator Ninoy Aquino) promise to Chairman Misuari as he sought his support for the struggle against Marcos while the former was abroad. The MNLF also supported Mrs. Aquino’s candidacy for president during the snap election in February 1986.

Chairman Misuari accepted President Aquino’s offer of autonomy rather than secession but on single autonomy instead of two, which President Marcos Sr. earlier created. The same constitutional process, however, led to the collapse of the peace talks. While Chairman Misuari insisted on the implementation of the Tripoli Agreement without plebiscite, the government instead created an Organic Act for the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), that, in accordance with the new 1987 constitution, calls for a plebiscite in 13 provinces and 9 cities whether to join the ARMM or not, as stipulated in the Tripoli Agreement. Only 4 provinces (Tawi-Tawi, Sulu, Maguindanao, and Lanao del Sur) voted yes. Under Article 2, Section 22 of the 1987 Philippines Constitution “the State recognizes and promotes the rights of indigenous cultural communities within the framework of national unity and development.” Further constitutional provision for Islamic education is effectively guaranteed under Article 14, Section 2.4, which states that “the State shall encourage non-formal, informal and indigenous learning systems as well as self-learning, independent and out of school study programs and particularly those that respond to community needs” […]; and Section 17: “Further, the State shall recognize, respect and protect the rights of indigenous cultural communities to preserve and develop their cultures, traditions and institutions. It shall consider their rights in the formulation of national plans and policies.” These provisions provided windows for government assistance to Islamic education in the succeeding years.

The MNLF boycotted the plebiscite for the second time and rejected the ARMM. But despite the failure of the peace talks, the government had earlier succeeded in getting the MNLF to sign an indefinite ceasefire which caused further split within the MNLF. The MILF also launched a five-day assault on January 1987 as a protest for their exclusion. It was also during this period when the Abu Sayyaf Group was born.

Sources:

Iribani, Abraham. 2006. Give Peace a Chance: The Story of the GRP-MNLF Peace Talks. Mandaluyong City: Magbassa Kita Foundation.

Majul, Cesar A. 1985. The Contemporary Muslim Movement in the Philippines. Berkeley: Mizan Press.

Vitug, Marites D. and Glenda M. Gloria. 2000. Under the Crescent Moon: Rebellion in Mindanao. Ateneo Center for Social Policy and Public Affairs. Teachers’ Village, Quezon City: Katipunan, Quezon City and Institute for Popular Democracy.

The 1987 Constitution. https://lawphil.net/consti/cons1987.html

Read More

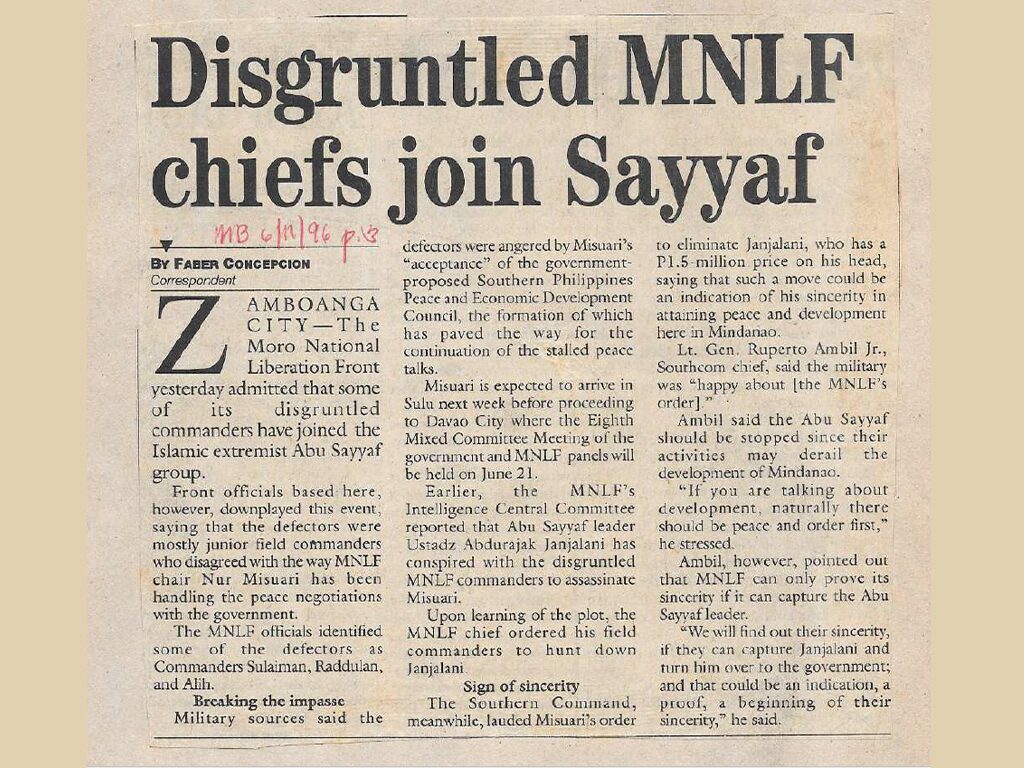

The Rise of the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG)

The Rise of the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG)

Unhappy with the failure of the peace talks and how MNLF and MILF leaders compromised the call for independence, Ustadz Abdurajak Janjalani and other young MNLF leaders established the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) and waged Jihad against the government.

Born and raised in Basilan to a Tausug father and a Christian mother from Iloilo, Ustadz Abdurajak Janjalani was a charismatic religious preacher. Without finishing his high school in Claret, a Christian school in Isabela, Basilan, Janjalani went to study Islamic Law at Umm Al-Qurah University in Makkah in 1981. Three years after, he came back and started preaching Islam and reform in Basilan. He urged school administrators not to prohibit Muslim women students from wearing hijab (head cover) and not to require them to wear shorts during P.E. classes. In 1987, he entered Da’wa Islamiyyah (Islamic Propagation) in Tripoli, Libya, which was the main base of the MNLF abroad.

From his longing to build an Islamic City at Kapayawan in Isabela, Basilan, Ustadz Janjalani openly preached Jihad. He called for the reform of the MNLF and MILF conduct. In 1990, he released a manifesto primarily addressed to the MNLF, asking the organization not to compromise with the government, pursue the struggle until Islamic state is established, and not to let the Philippine constitution be above the glorious Qur’an. He went around the provinces in the south to preach and also to get the opinion of many leading Ulama and MNLF senior leaders on what to do with the current failing struggle. He delivered sermons in a mosque in Zamboanga and gave lectures at the Western Mindanao State University (WMSU) where he recruited many student leaders and activists in the early ’90s.

In August 1991, a big ship, M/V Doulos, a trans-shipping line owned by a Christian charity organization docked in Zamboanga City carrying Christian missionaries who brought with them literature for sale. The missionary group was on an evangelical tour. Accordingly, in a convocation in Western Mindanao State University before faculty and students, both Christians and Muslims, the missionaries spoke against Islam and called Allah as false God, Muhammad a liar, and the Qur’an a man-made book. Some Muslim students who heard the insult informed Ustadz Janjalani about the supposed blasphemy did by the said missionary group. When there was no action taken by the Muslims, Ustadz Janjalani and his followers bombed the boat, killing two missionaries and wounding thirty-eight others. It was during this time wh

en the name Abu Sayyaf was publicly used by Ustadz Janjalani. He and his group went underground and staged Islamic Jihad against the government. He was joined by some MNLF local leaders, such as Raddulan Sahiron from Sulu. On April 04, 1995, they and some MNLF commanders attacked and burned down the town of Ipil in Zamboanga Sibugay leaving 53 dead and 43 injured.

The threat of Islamic radicalism by the Abu Sayyaf prompted both the MNLF and the government under President Ramos Administration to revive the 1976 Tripoli Agreement.

Sources:

Tan, Samuel K. 2010. Muslims South and Beyond. Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Press.

Absari, Darwin J. “The Bangsamoro Armed Struggle: Dynamics of Split and the Rise of Islamic Radicalism.” Unpublished article funded by the International Alert – Philippines.

Wadi, Julkipli. Trans. 1998. “The Abu Sayyaf: Radical Ideas of Abdurajak Janjalani Abubakar.” Translated into English. Research Study submitted to the Center for Integrative Development Studies, University of the Philippines.

Vitug, Marites D. and Glenda M. Gloria. 2000. Under the Crescent Moon: Rebellion in Mindanao. Ateneo Center for Social Policy and Public Affairs. Teachers’ Village, Quezon City: Katipunan, Quezon City and Institute for Popular Democracy.

Banlaoi, Rommel C. 2019. AL-HARAKATUL AL-ISLAMIYYAH: Essays on the Abu Sayyaf Group Terrorism in the Philippines from Al-Qaeda to ISIS. 4th Edition. Manila: Philippine Institute for Peace, Violence and Terrorism Research.

Read More

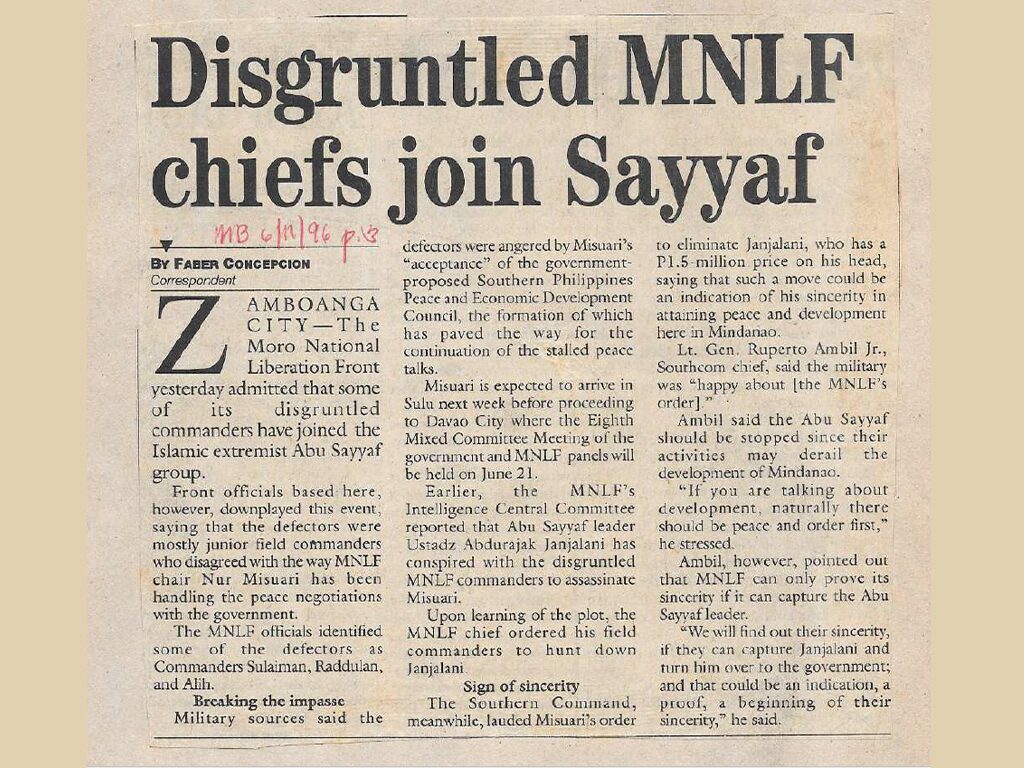

The 1996 Final Peace Agreement

The 1996 Final Peace Agreement

On September 02, 1996, President Fidel Ramos and MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari signed the Final Peace Agreement which sought to fully implement the Tripoli Agreement. During this period, Chairman Misuari was elected as ARMM governor and appointed head of the Southern Philippines Council for Peace and Development (SPCPD). Thousands of MNLF fighters were integrated to both the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine National Police. However, the peace agreement ended because of a renewed war in Sulu and Zamboanga. Chairman Misuari fled to Malaysia only to be arrested by the Malaysian authority in November 2001. President Ramos’s peace...

After the failed talks with President Aquino, MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari was already losing grip on the MNLF. President Fidel Ramos, on the other hand, wanted to be remembered as peacemaker. Being a retired military man, he knew very well the Muslims’ armed resistance, dynamics within the Bangsamoro fronts as well as the history of peace negotiations. Even before the 1996 Final Peace Agreement was signed, he had already Chairman Misuari accept the offer of governorship of ARMM despite the opposition of many MNLF senior leaders and some foreign Muslim diplomats. He also appointed Chairman Misuari as head of the Southern Philippines Council for Peace and Development (SPCPD), an administrative alternative to the provisional government that would ”improve the living conditions, promote peace, and develop the region in the Southern Philippines.” This “package deal” as Chairman Misuari asserted, has exposed him to failure and criticism. Indeed, the positions of ARMM governorship and the chairmanship of Southern Philippine Council for Peace Development (SPCPD) offered to him by President Ramos were not fruitful as it was expected to be.

Chairman Misuari accused the government of not fully implementing the agreement, while the government accused him of corruption and mismanagement. It was also during this time that the Muslims’ high regard of him dramatically declined as many MNLF combatants did not benefit from the peace dividends, while many have been integrated into the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) and the Philippine National Police (PNP) as part of the agreement. This period also triggered another split of most of his remaining faithful top leaders. They were to become known as the Executive 15 (EC15). One of the EC15, his chief of Foreign Affairs, Doctor Parouk Hussin, succeeded him as ARMM governor.

Meanwhile, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) began to emerge as another formidable force. Just a month after the signing of the 1996 Final Peace Agreement, the MILF launched series of attacks in Basilan, Zamboanga del Norte, and North Cotabato.

President Ramos initiated separate negotiations with the MILF. From 1996 to 2000, the government and the MILF entered into a total of 39 agreements. But no resolution was reached despite MILF’s acknowledgement of a political solution that does not necessarily mean independence for the Muslims. And all these agreements were wasted when President Ramos’s successor declared an all-out war.

Sources:

Jubair, Salah. 2007. The Long Road to Peace: Inside the GRP-MILF Peace Process. Davao City: Institute of Bangsamoro Studies.

Santos, Soliman. 2005. Dynamics and Directions of the Peace Negotiations Between the Philippine Government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. Davao City: Alternate Forum for Research in Mindanao.

Vitug, Marites D. and Glenda M. Gloria. 2000. Under the Crescent Moon: Rebellion in Mindanao. Ateneo Center for Social Policy and Public Affairs. Teachers’ Village, Quezon City: Katipunan, Quezon City and Institute for Popular Democracy.

https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2001/11/30/141875/145war-not-yet-over146

https://edition.cnn.com/2001/WORLD/asiapcf/southeast/11/26/phil.hostage/

Read More

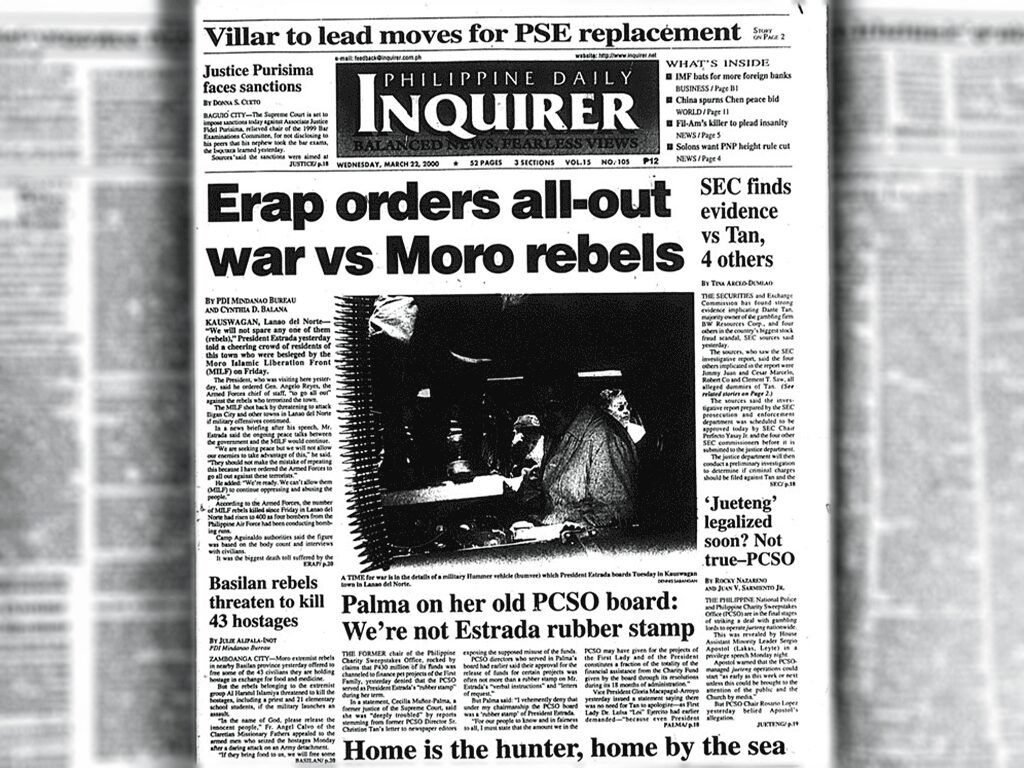

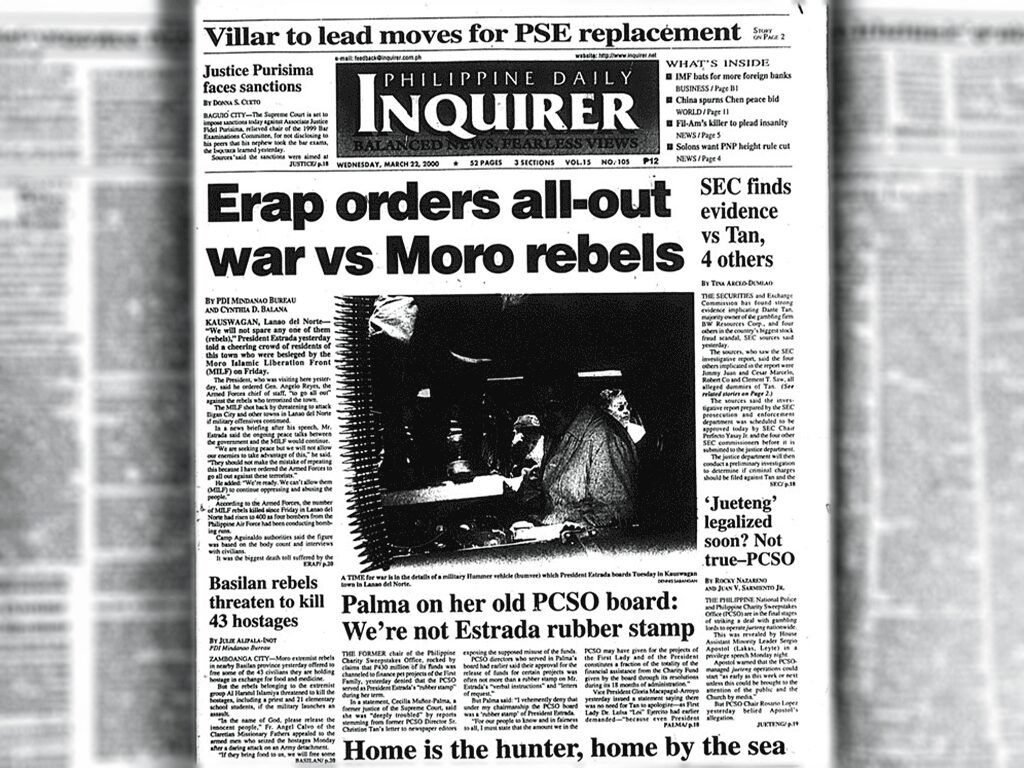

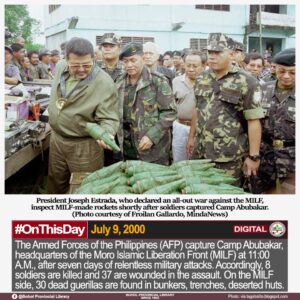

Estrada’s All Out War Against MILF in 2000

Estrada’s All Out War Against MILF in 2000

On March 21, 2000, President Joseph “Erap” Estrada declared an all-out war against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). A more than three-month bloody encounter ended with the fall of Camp Abubakar to the military but did not put an end to the MILF’s secession movement. And the Abu Sayyaf Group was still on a rampage.

The cycle of truce and war led President Joseph “Erap” Estrada to mistrust the Muslims despite the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) support for his bid for presidency. Attempts to bring the MILF to a negotiating table failed. President Estrada gave the MILF an ultimatum to back down while the MILF insisted on their demand for a substate. On March 21, 2000, after the MILF invaded the town of Kauswagan, Lanao del Norte, President Estrada ordered an all-out war against the MILF. The war lasted

more than three months. On July 9, 2000, after seven days of relentless military attacks, MILF Chairman Ustadz Salamat left Camp Abubakar to reposition in other camps.

The all-out war which cost the government more than a billion pesos and displaced thousands of civilians did not, however, put an end to the MILF secession movement.

Meanwhile, the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) remained a serious threat to the government’s peace efforts in Basilan and Sulu.

After the death of the ASG’s founder Ustadz Abdurajak Janjalani in a police encounter in Basilan in 1998, his Islamic jihad died with him, and the group he left split into many factions. Many original members left and lay low, while some resorted to banditry and kidnapping. In the succeeding years, kidnap for ransom became the main activity of the ASG. From 2000-2001, the ASG has conducted 140 kidnap-for-ransom activities (KRA), the famous of which is the Sipadan kidnapping of 21 tourists in 2000. This idea of KRA however was introduced by the Philippine National Police’s (PNP) deep penetrating agent Edwin Angeles, a half-Muslim and a half-Christian whom the PNP planted to infiltrate the ASG.

Sources:

Vitug, Marites D. and Glenda M. Gloria. 2000. Under the Crescent Moon: Rebellion in Mindanao. Ateneo Center for Social Policy and Public Affairs. Teachers’ Village, Quezon City: Katipunan, Quezon City and Institute for Popular Democracy.

Banlaoi, Rommel C. 2019. AL-HARAKATUL AL-ISLAMIYYAH: Essays on the Abu Sayyaf Group Terrorism in the Philippines from Al-Qaeda to ISIS. 4th Edition. Manila: Philippine Institute for Peace, Violence and Terrorism Research.

https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/668386/estrada-stands-by-all-out-war-strategy-vs-milf#ixzz8iClHC1nE

Read More

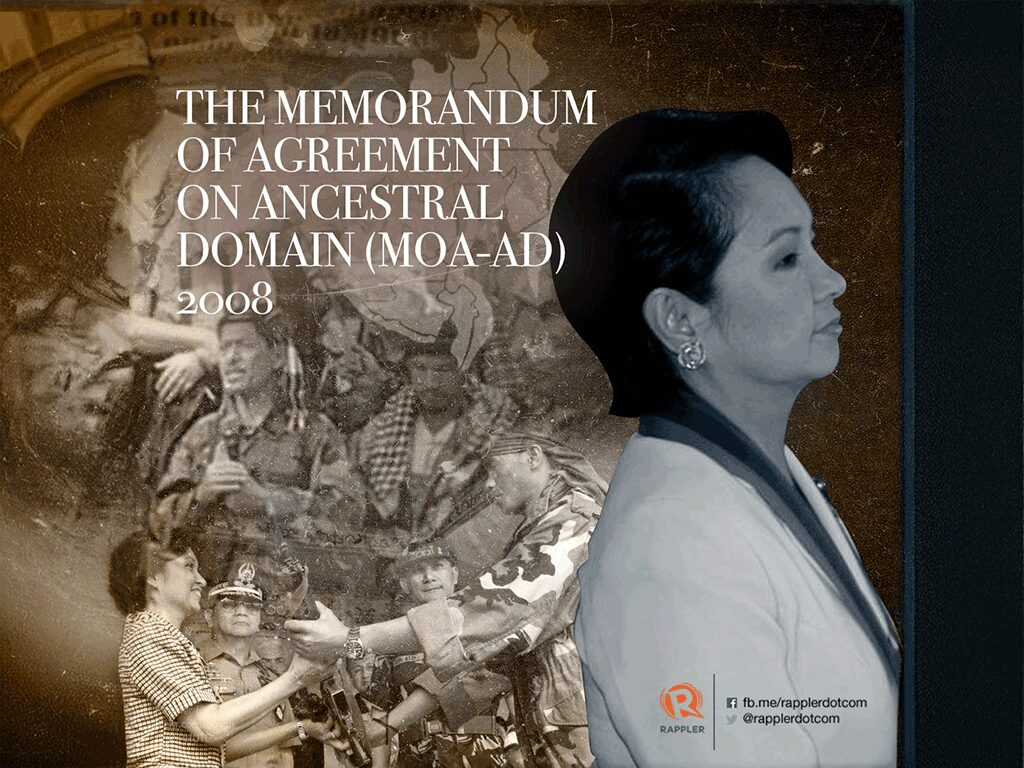

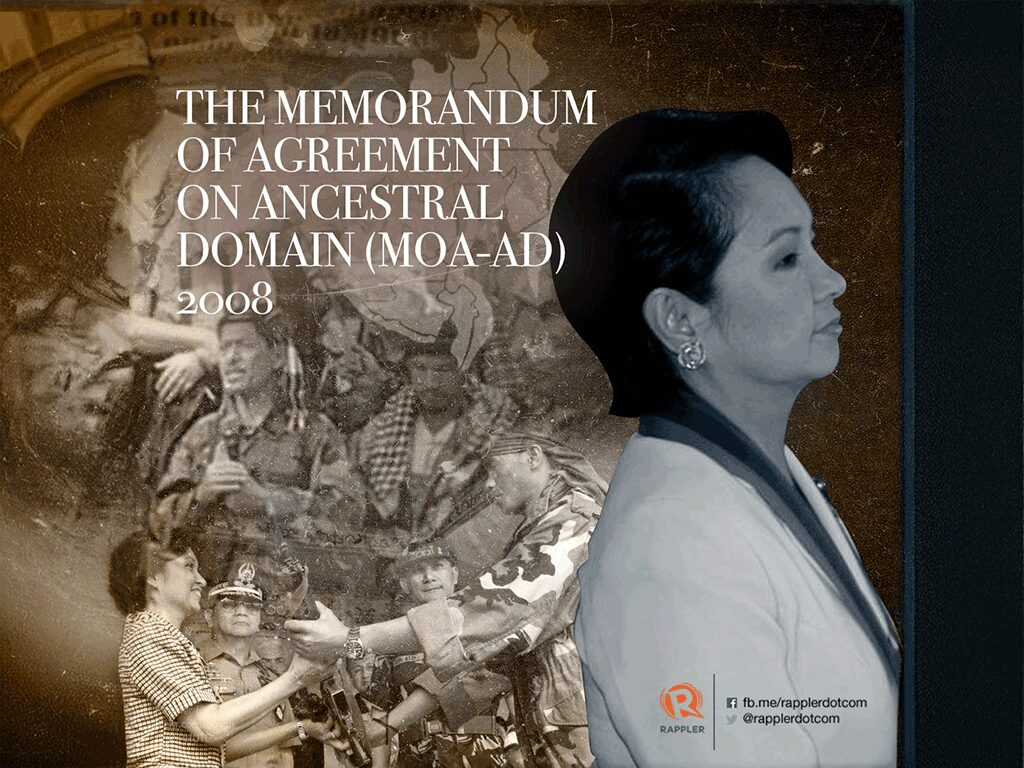

The 2008 Memorandum of Agreement and on Ancestral Domain

The 2008 Memorandum of Agreement and on Ancestral Domain

After being sworn in as president in January 2001, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo launched an all-out peace with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). But the Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD) which she signed in 2008 was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. Umbra Kato broke away and formed the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari was about to end his term as ARMM Governor, and the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) was still on its Kidnap for Ransom Activities.

Gloria Macapagal Arroyo was vice president when an all-out war was declared by President Erap Estrada in March 2000. In less than a year, President Estrada was ousted by the Second People Power Revolution which installed Arroyo as president in January 2001. Reversing her predecessor’s policy, she launched an all-out peace with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). In June of the same year, the government and the MILF signed an agreement in Tripoli, Libya. The agreement focused on Security, Rehabilitation, and Ancestral Domain.

Meanwhile, Chairman Misuari’s previous request to President Estrada to extend the term of the SPCPD for another three years and postpone the referendum on expanding the ARMM for three years was denied. This resulted in the attack of the military infantry brigade headquarters in Indanan, Sulu, by some of his loyalist members on November 19, 2001. Chairman Misuari fled to Malaysia but was arrested by the Malaysian Authority and deported back to the Philippines. A week after, his other loyal members in Cabantangan office, an area allocated to the MNLF in Zamboanga, refused to vacate the complex and fought the military. Air strikes forced them to leave, taking more than a hundred civilian hostages.

Previously, on June 02, 2001, the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) led by Abu Sabaya and Khadafi Janjalani entered the town of Lamitan in Basilan with their twenty hostages including three American nationals which they kidnapped in Dos Palmas Resort in Palawan on May 27, 2001. But despite being surrounded by the military inside St. Peter’s Church and the Jose Torres Memorial Hospital, they managed to escape along with their hostages.

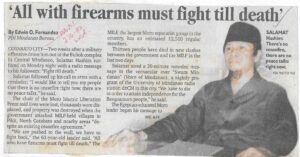

Peace talks with the MILF were also suspended for a year when the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) launched an operation to capture MILF’s new headquarters in Buliok in the town of Pikit in Cotabato province in 2002. MILF Chairman Ustadz Salamat Hashim declared Jihad (Holy War) and called every Muslim with a firearm to fight to the death. The same year, President Arroyo launched a major battle against the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) in Sulu and Basilan that killed Abu Sabaya, the ASG Basilan faction leader.

It was only in 2008 when President Arroyo announced the Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD) with the MILF that aims to establish a substate called Bangsamoro Juridical Entity (BJE). However, the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional. As a result, Ombra Katu, along with his troops, broke away from the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), formed his Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), and continued the war for independence. Also in Lanao, Abdullah Macapaar known as Kumander Bravo, commander of northwestern Mindanao, led an attack on Lanao del Norte’s town of Kauswagan. During this time, Ustadz Salamat already passed away. He died of heart ailment and acute ulcer in 2003, and he was succeeded by Vice Chairman for Military Affairs Ahod ‘Murad’ Ebrahim.

Nevertheless, President Arroyo’s term ended with the expansion of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), which resulted in the inclusion of Basilan and the Islamic City of Marawi. Eid al-Fitr (end of Ramadan) and Eid’l Adha (Feast of Sacrifice) were declared national holidays. It was also during her presidency that President Marcos Sr.’s program on mainstreaming Madrasah Education was realized through the Department of Education (DepEd). Arabic Language and Islamic Values (ALIVE) started to be taught in public schools within ARMM so that Muslim students will no longer go to private Madrasah (Islamic schools) during the weekend to learn Islam. Private Madrasah can also avail of accreditation to get financial assistance, and their graduates can pursue higher learning in public schools. In 2010, she abolished the Office of Muslim Affairs (OMA) and replaced it with the National Commission on Muslim Filipinos (NCMF) with more expanded programs such as the promotion and development of the Philippine Halal Industry to cater to the growing needs of all Muslims in the country.

Sources:

Manila Bulletin, June 22, 2002. News Clippings of the UP Diliman Institute of Islamic Studies.

Philippine Daily Inquirer, June 29, 2002. News Clippings of the UP Diliman Institute of Islamic Studies.

Philippine Daily Inquirer, February 23, 2003. News Clippings of the UP Diliman Institute of Islamic Studies.

https://peace.gov.ph/timeline/peace-process-milf/

https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2001/02/23/89858/arroyo-signs-new-armm-organic-act

https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2002/11/14/183916/145eid-al-fitr146-now-national-holiday

https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/100801/ameril-umra-kato-dead-muslim-leader

Read More

President Aquino’s Bangsamoro Basic Law and the Crises of Peace Talks

President Aquino’s Bangsamoro Basic Law and the Crises of Peace Talks

In August 2011, President Benigno ‘Pnoy’ Aquino Jr. flew to Japan to meet Ustadz Salamat Hashim’s successor, Ahod Ebrahim to renew the peace negotiations with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). The result was the 2012 Framework Agreement of the Bangsamoro (FAB), 2014 Comprehensive Agreement of the Bangsamoro (CAB), and the 2015 Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL). These serious efforts to bring lasting peace in Mindanao, however, were challenged by a series of major crisis, the 2013 Sabah Standoff and Zamboanga Siege, and the 2015 Mamasapano incident that finally halted the peace agreement in the House of Congress.

President Benigno Aquino Jr., the son of the late Senator Benigno Aquino Sr. and President Corazon Aquino, was pushed to run for the presidency in the 2010 elections after his mother died in 2019. He won. In August 2011, he left for Japan unannounced to meet Ustadz Salamat Hashim’s successor, Ahod ‘Murad’ Ebrahim, to fast-track the peace negotiations with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). A year later, both parties signed the Framework Agreement of the Bangsamoro (FAB) on October 18, 2012, which seeks to establish a Bangsamoro entity that would eventually replace the existing Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) that according to President Aquino, was a failed experiment. A Transition Commission was created to draft the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL). The agreement includes, among others, the normalization program that would eventually decommission MILF’s forces. the creation of Bangsamoro Police Force and also creation of a Transitional Justice to address the legitimate grievances of the Bangsamoro people, correct historical injustices, and address human rights violations.

In his commitment to peace, President Aquino Jr. brushed aside the urge from some policy makers to declare an all-out war against the MILF following the death of 19 soldiers in an encounter in Basilan. FAB was followed by the Comprehensive Agreement of the Bangsamoro (CAB) in March 2012. The CAB was the consolidation of numerous accords and agreements between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) that will pave the way for establishing the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). The House of Congress was expected to pass the BBL in 2015.

The success in the continuing peace talks was, however, disrupted when 80-100 Royal Forces of Sulu Sultan led by Datu Agbimuddin Kiram went to Lahad Datu, North Borneo, to assert Sulu’s Territorial of North Borneo, in February 2013. This resulted in the bilateral crisis between the Philippines and Malaysia which was serving as the third party in the peace negotiations with the MILF. MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari openly supported the so-called invasion and demanded representation in the ongoing peace negotiations. Both Chairman Misuari and Sulu Sultan were left out in the ongoing peace negotiations with the MILF. The crisis lasted two months with Datu Agbimuddin fighting against massive military assaults launched by the Malaysian government despite the appeal for a dialogue by President Aquino.

In August of the same year, while in Sulu, MNLF Chairman Misuari declared independence of the Bangsamoro Republik with him as the commander. This was followed by a siege in Zamboanga City in September by the MNLF Sulu State Revolutionary Command (SSRC) led by Ustadz Habir Malik. This immediately turned into a national security crisis that lasted twenty-eight days resulting in the displacement of 82,000 residents and the destruction of almost 1,000 buildings.

The biggest tragedy that led to the death of the BBL in congress was the Mamasapano incident in January 2015. But Ferdinand Martin Romualdez, who was then representative of Leyte believed the proposed BBL was already doomed even before Congress amended it because it contained several unconstitutional provisions. He said the Mamasapano clash may have been “providential” as the 44 SAF troopers’ deaths served as a “wake up call” for the government that time is not yet ripe for the proposed BBL’s passage.

At any rate, President Aquino’s administration left a legacy of Integrated History Act, a bill that was passed into law mandating the integration of Filipino-Muslim and indigenous people’s history, culture, and identity in the study of Philippine history in both basic and higher education. This is a bill previously filed by Lanao del Sur Congressman Pagalian M. Balindong. The first mosque in Simunul, Tawi-Tawi, was also declared as National History Landmark. These and other previous positive developments contributed to the bridging of religious and cultural gaps among Filipino Christians and Muslims in the country.

Sources:

Sakili, Abraham P. 2012. The Bangsamoro Framework Agreement and the Mindanao Problem: Foregrounding Historical and Cultural Facts and Concepts for Social Justice and Peace in the Southern Philippines. Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspective in Aisa. Volume 48 Numbers 1 & 2.

Heydarian, Richard Javad. 2015. Report on The Quest for Peace: The Aquino Administration’s Peace Negotiations with the MILF and CPP-NPA-NDF. Norwegian Peace Building Resource Centre.

https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/189990/6a4a521651243abd9d63bafa322d7da9.pdf

https://www.scribd.com/document/137673080/Framework-Agreement-on-the-Bangsamoro

https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/36947/aquino-milf-chief-talk-peace-in-tokyo

https://peace.gov.ph/timeline/peace-process-milf/

https://globalnation.inquirer.net/64577/heirs-of-sultan-of-sulu-pursue-sabah-claim-on-their-own

https://www.philstar.com/nation/2013/08/15/1094161/nur-declares-independence-bangsamoro-republik

https://www.rappler.com/philippines/mindanao/zamboanga-city-remembers-2013-siege/

https://issuances-library.senate.gov.ph/subject/integrated-history-act-of-2016

https://jur.ph/law/summary/sheikh-karimul-makhdum-mosque-as-national-historical-landmark

Read More

2015 Mamasapano Incident – BBL Died with SAF 44

2015 Mamasapano Incident – BBL Died with SAF 44

44 members of the Philippine National Police (PNP) Special Action Force (SAF) died in an encounter with the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF) in Mamasapano in January 2015. The incident which the media dramatized as massacre prompted the House of Congress to halt the MILF-GRP peace process. This incident led to the rise of the Maute Brothers.

Early morning of January 25, 2015, the Special Action Force (SAF) of the Philippine National Police (PNP) entered the Mamasapano area in Maguindanao to arrest Zulkifli Abdhir known as Marwan who had been hiding in Mindanao with Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF).

Marwan was a bomb maker and the most wanted terrorist in the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) with a 5 million US Dollar bounty on his head. He was suspected of leading the Kumpulan Mujahidin Malaysia (KMM), which was part of the central command of the Jemaah Islamiyah (JI), and of involvement in the 2002 Bali bombings in 2002.

The arrest mission called Operation Exodus resulted in an encounter with the BIFF that killed 44 members of the SAF. Mainstream media dramatized the incident as a massacre, but the findings of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) says that it was a misencounter since both the BIFF and SAF did not intend to fight. The House of Congress on February 02, 2015, went on to halt the passage of the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) that jeopardized the GRP-MILF peace process. this led to the rise of the Maute Brothers.

Two years later, on January 01, 2017, President Rodrigo Duterte in his speech at Malacañang Palace addressed to the families of the Fallen SAF 44 exposed the CIA involvement in the operation. He further said that the arrest mission without coordinating with the MILF was a violation of the MILF-GRP peace agreement since there was an existing ceasefire agreement signed in Basilan on November 10, 2008, which created the Coordinating Committee on the Cessation of Hostilities (CCCH) and Ad Hoc Joint Action Group (AHJAG).

Sources:

https://discover.hubpages.com/politics/SAF-44-Mamasapano-Clash-in-the-Philippines

https://manilastandard.net/?p=169810

https://peace.gov.ph/2022/11/govt-milf-sign-ceasefire-agreement-in-basilan/

Read More

President Duterte’s War and Peace Efforts

President Duterte’s War and Peace Efforts

Knowing well the complexities of the Muslims’ armed struggle and the dynamics within the Bangsamoro armed groups, President Rodrigo Duterte laid down a more inclusive peace deal with both the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). But he has yet to confront the consequences of the failure of previous peace talks, the Abu Sayyaf and Maute Groups.Before he became president, Rodrigo Duterte has been mayor of Davao City in Mindanao for quite long. His acquaintance with many Muslim leaders including MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari and MILF Chairman Ahod Ebrahim made him familiar with the long history of the Muslims’ armed resistance and the dynamics within the Bangsamoro armed groups.

https://peace.gov.ph/timeline/peace-process-milf/

Immediately after his victory as president in the May 2016 elections, President Duterte sought to meet the MILF leaders including former MNLF Vice Chairman of the Central Committee Abulkhayr Alonto in his home city in Davao. Two months after, he approved a roadmap on the Bangsamoro peace process involving the implementation and consolidation of all signed peace agreements and pertinent legislation which was part of his six-point peace and development agenda. Then on November 07, 2016, he signed Executive Order (EO) No. 8 reconstituting the Bangsamoro Transition Commission (BTC). This EO sought to establish a broader BTC, which would be responsible for drafting a law that would lay the legal groundwork for the future

Bangsamoro government in Mindanao. The EO also aimed to ensure that all stakeholders, including local government units (LGUs), women, youth, and other sectoral groups, were involved in the law’s creation, addressing concerns about the exclusion of certain groups during the drafting of the previous BBL. Additionally, the expanded BTC members from 15 to 21 included representatives from the MNLF breakaway group led by Muslimin Sema, who were allocated three seats on the commission by the government. This was a few days after the president had granted MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari temporary freedom from the case of his alleged involvement in the 2013 Zamboanga Siege. A separate talk with MNLF Chairman Misuari in his hometown where President Duterte housed him was also pursued.

Meanwhile, he deployed at least 7,000 troops to launch a massive military campaign against the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) in Sulu a week after a bomb exploded on September 02, 2016, that killed 14 people and injured more than 60 in a night market in Davao City. But while he was able to neutralize the ASG in Sulu, a new group, The Maute-ASG Basilan Alliance Group, attacked Marawi City in May 2017 which compelled him to declare Martial Law in Mindanao.

Sources:

https://peace.gov.ph/2016/11/pres-duterte-to-sign-eo-btc/

https://peace.gov.ph/2016/11/eo-activates-enhanced-btc-seeks-inclusivity-bangsamoro-peace-process/

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/9/10/philippines-duterte-warns-more-bombings-likely

https://edition.cnn.com/2017/05/23/asia/philippines-mindanao-clashes-martial-law/index.html

Read More

The Birth of Maute-ASG Alliance and the Marawi Siege

The Birth of Maute-ASG Alliance and the Marawi Siege

The death of the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) in the House of Congress in February 2015 caused widespread frustration within the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). It was at this point that the Maute brothers started to openly criticize the government and pushed for an Independent Islamic State. Their combined forces with Isnilon Hapilon, Abu Sayyaf Group leader in Basilan, finally attacked Marawi City in May 2017 that destroyed almost the entire city.

https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2017/11/philippines-battle-of-marawi-leaves-trail-of-death-and-destruction/

Like the Abu Sayyaf, Omar and Abdullah Maute, known as the Maute Brothers, were born out of the compromised struggle and failure of peace negotiations between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). When the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) was halted in the House of Congress in February 2015, Many MILF leaders and members were frustrated. One of them was Engr. Cayamura, father of the Maute Brothers, Omar and Abdullah.

Engr. Cayamura was a visionary and reformist. Before his sons attacked Marawi City, he was the president of Insan Islamic Assembly (ISA), a local Islamic organization founded in the 70s. When many secular organizations such as fraternities were established in MSU’s main campus in Marawi, ISA recruited many M’ranao students. Engr. Cayamura wanted to save students from those secular organizations by promoting Islamic values to young Muslims. This reform he wanted to do was carried on by his sons when they came back from abroad.

Omar who wanted to become a peacemaker when he graduated from high school from Dansalan College (the only Christian college in Marawi) came home with radical Islamic ideology. He studied Islamic theology in Egypt while his brother Abdullah in Jordan. It was not certain whether their schooling abroad was part of their father’s plan of reforming their areas. It was not also certain where abroad Omar became radical. His classmates in Egypt recalled no signs of radical thoughts when he was there. But his Indonesian father-in-law accordingly sent him home after learning that he was teaching Islamic radical ideas in his school in Indonesia where he let Omar teach.

When the Maute brothers came home, they started to organize and introduce reform in Marawi by imposing the wearing of hijab (head cover) for Muslim women including those students in MSU Marawi. They prohibited karaoke, the selling of liquor, and started killing drug dealers.

When the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) was killed in the House of Congress in 2015, the Maute Brothers openly pushed for the Islamic State previously advocated by Ustadz Janjalani. In 2016, the same year Hapilon attacked the military in Tipo-Tipo, Basilan, they attacked the military in Butig. It was here that they became known.

Isnilon Hapilon was a student of the founder of the Abu Sayyaf Group, Ustadz Abdujarak Janjalani. After the death of Khadafy and Aldam Tilao (Abu Sabaya) in 2002, he took care of the Abu Sayyaf Basilan faction. To revive the Islamic ideology that his mentor, Ustadz Abdurajak has advocated, in 2014, he swore allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the ISIS leader in 2014. While he was able to get the recognition of the ISIS when he was designated Amir (leader) of Southeast Asia, he failed to get the support of the local people due to the questionable credibility and authenticity of the ISIS call for the Islamic Caliphate. It was in Marawi City where he found a strong ally. A heavy military campaign response against his attack in 2016 forced him to escape to Marawi City where he joined the Maute Brothers. In May 2017, their combined forces attacked Marawi City.

In a video uploaded on YouTube during the war, Abdullah called all M’ranaos to fight with them because he said, the death of BBL in Congress shows how the government continuously betrayed the Muslims and that they should wage Jihad to establish an independent Islamic State. Omar and Isnilon, along with many of their followers, were killed in the war that lasted nearly six months displacing 98 percent of the total population of the city that was almost destroyed.

Sources:

Absari, Darwin J. The Bangsamoro Armed Struggle: Dynamics of Split and the Rise of Islamic Radicalism. Unpublished article.

https://www.unhcr.org/ph/marawi-crisis

Read More

The 2018 Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (BARMM)

The Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL) and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (BARMM)

On July 26, 2018, just three days after he delivered his third State of the Nation Address (SONA), President Duterte signed the Bangsamoro Organic Law. The long history of peace negotiations with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) finally came to fruition. The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) was established with the MILF Chairman Ahod “Murad” Ebrahim as its interim chief minister.

The Marawi siege that occurred in May 2017 did not stop President Duterte in pursuing peace in Mindanao. Barely two months after, the first draft of the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL) was submitted to him on July 17, 2017.

After the first public consultation in Mindanao from May 30-31, 2018, led by Senators Zubiri, Angara, Ejercito, and Hontiveros in Cotabato, the House of Representatives unanimously passed the BBL on its third and final reading. This bill, which aims to replace the ARMM, was certified as urgent by President Rodrigo Duterte and passed with 227 votes in favor, 11 against, and 2 abstentions. The final version of the BBL, which was renamed the Organic Law for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, or the Bangsamoro Organic Law (BOL), also known as Republic Act No. 11054 was approved by the 29-member bicameral committee on July 18, 2018, after six days of late-night discussions and multiple challenges. On July 23, 2018, the House of Representatives and the Senate ratified the proposed Bangsamoro Organic Law. Finally, on July 27, 2018, President Rodrigo Duterte signed Republic Act No. 11054, known as the Bangsamoro Organic Law, three days after delivering his third State of the Nation Address and following the law’s ratification by both the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Challenge to peace, however, continued when Jolo Cathedral was bombed by an alleged foreign terrorist. At least 20 people, military and civilians, were killed and 111 injured. The bombing took place a few days after the plebiscite for the BBL that would create the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (BBL). Sulu also voted to be excluded from the said BARMM. Still, this incident did not hamper President Duterte’s commitment to peace. Finally, on March 09, 2019, the Bangsamoro Transition Authority that would govern the BARMM was inaugurated with MILF chairman as the interim chief minister. Kumander Bravo was also appointed BTA member. the BTA is composed of 80 members, 41 will be appointed by MILF while the remaining 39 will come from the government side.

The BARMM consists of 5 provinces, 3 cities, 116 municipalities, 2,590 barangays, and 1 special geographic area (SGA) with assured funding of an annual block grant which is 5% share of the national internal revenue or some 59 billion pesos. Before his term ended, President Duterte approved the extension of the BTA until 2025.

Sources:

https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/995859/house-approves-bbl-on-third-and-final-reading

https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1036976

https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1011517/bicam-approves-bangsamoro-organic-law

https://legacy.senate.gov.ph/press_release/2018/0724_prib4.asp

https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1014757/duterte-signs-bangsamoro-organic-law

https://peace.gov.ph/2018/07/prrd-signs-bangsamoro-organic-law/

https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1078076/jolo-sulu-blast-bombing-death-toll-injured-news

https://www.rappler.com/philippines/208331-document-bangsamoro-organic-law/

Read More

Passage of the BOL Prescribed Codes in the BARMM

2019 - 2022

Passage of the BOL Prescribed Codes in the BARMM

With the establishment of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) Parliament continuously strives to enact key legislations to lay the groundworks of governance in the BARMM as indicated in Republic Act 11054 or the Bangsamoro Organic Law.

At present, the BTA Parliament for its first set of parliament members from 2019-2022 and the second set of BTA members (2022-2025) were able to enact five priority codes: the Bangsamoro Administrative Code on October 28, 2020; the Bangsamoro Civil Service Code on February 24, 2021; the Bangsamoro Education Code on May 18, 2021; the Bangsamoro Electoral Code on March 9, 2023; and the Bangsamoro Local Governance Code on September 28, 2023.

The Bangsamoro Administrative Code defines the structural, functional, and procedural principles and rules of governance of the BARMM. As a newly established system from the defunct Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, the creation and reorganization of various institutions are put in place to complement the existing demands and future needs of the Bangsamoro people through a well-functioning bureaucracy. The Administrative Code also harmonizes relationships between and among created ministries, agencies, and offices while maintaining strong coordination with relevant national agencies in pursuit of their respective mandates and functions.

The Civil Service Code governs the conduct of civil servants, prescribes qualifications for nonelective positions, adopts an independent and credible merit and fitness system, protects civil service eligibles in various government positions, including government-owned and controlled corporations with original charters in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, and provides rules on disciplinary authority over the Bangsamoro government’s officials and employees.

The Education Code embodies the BARMM’s commitment to inclusive, relevant, and quality education with the principles of moral governance at its core. The Bangsamoro Education Code is seen to improve internal processing systems to promote acceptable governance practices, transparency, and accountability. It shall establish, manage, and support a complete and integrated system of quality education, which shall be a subsystem of the national education system. This includes the special eligibility for madrasah teachers, a tribal university system for the higher educational needs of the indigenous peoples, and peace education as a core component of the Bangsamoro education system.

In pursuit of the right to self-governance, the Electoral Code prescribes the structural, functional, and procedural principles in the conduct of elections, plebiscites, initiatives, referenda, recall proceedings, and encourages the formation of genuinely principled political parties in the BARMM. It consists of introductory provisions, the Bangsamoro Electoral Office under the supervision of the Commission on Elections (COMELEC), regional political parties in the Bangsamoro based on the parliamentary system of governance, elective positions in the parliament, elections upon dissolution of the parliament, the voters, election administration, election offenses, legal fees, transitory provisions, and final provisions.

The Local Governance Code enumerates powers to be devolved to the different levels of local governments, clearly defining the delineation of responsibilities between and among them including equitable revenue sharing, democratization, and empowerment of local communities. It also ensures that the constituents know what services and facilities are on the list and/or can be demanded from their local government. The Code grants authority to LGUs, placing them on par with other local governments in the country in terms of providing relevant services to their constituents. Regional ministries and offices will reorganize and restructure themselves to supplement local government services.

Aside from the priority Codes, the Bangsamoro Parliament was able to enact landmark legislations in the six-year period including the creation of the eight municipalities under the Special Geographic Area, the Bangsamoro Holidays Act, the transfer of the seat of governance from Cotabato City to Parang, Maguindanao del Norte, the establishment of the Bangsamoro Science High School System in the region, and redistricting of parliamentary seats in preparation for the first-ever parliamentary elections on 2025.

Sources:

https://www.rappler.com/philippines/bangsamoro-parliament-passes-administrative-code/

https://rasmitmug.com/ebooks/BCSC-4.pdf

https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1122161

https://www.rappler.com/philippines/mindanao/barmm-parliament-approves-electoral-code-march-8-2023/

https://bangsamoro.gov.ph/news/latest-news/barmm-education-code-signed-into-law/

https://parliament.bangsamoro.gov.ph/2023/09/28/bangsamoro-parliament-oks-local-governance-code/

https://parliament.bangsamoro.gov.ph/2023/03/09/barmm-approves-bangsamoro-electoral-code/

Read More

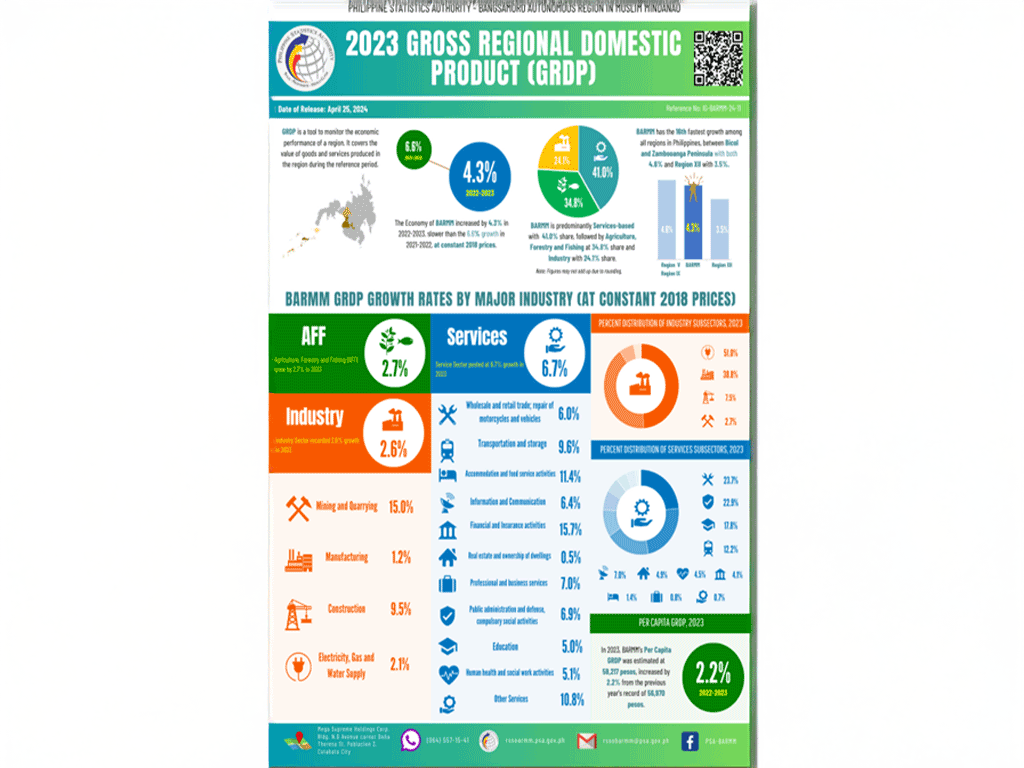

BARMM Marks Economic Growth and Shift from Agriculture to Service-Oriented Economy

2021

BARMM Marks Economic Growth and Shift from Agriculture to Service-Oriented Economy

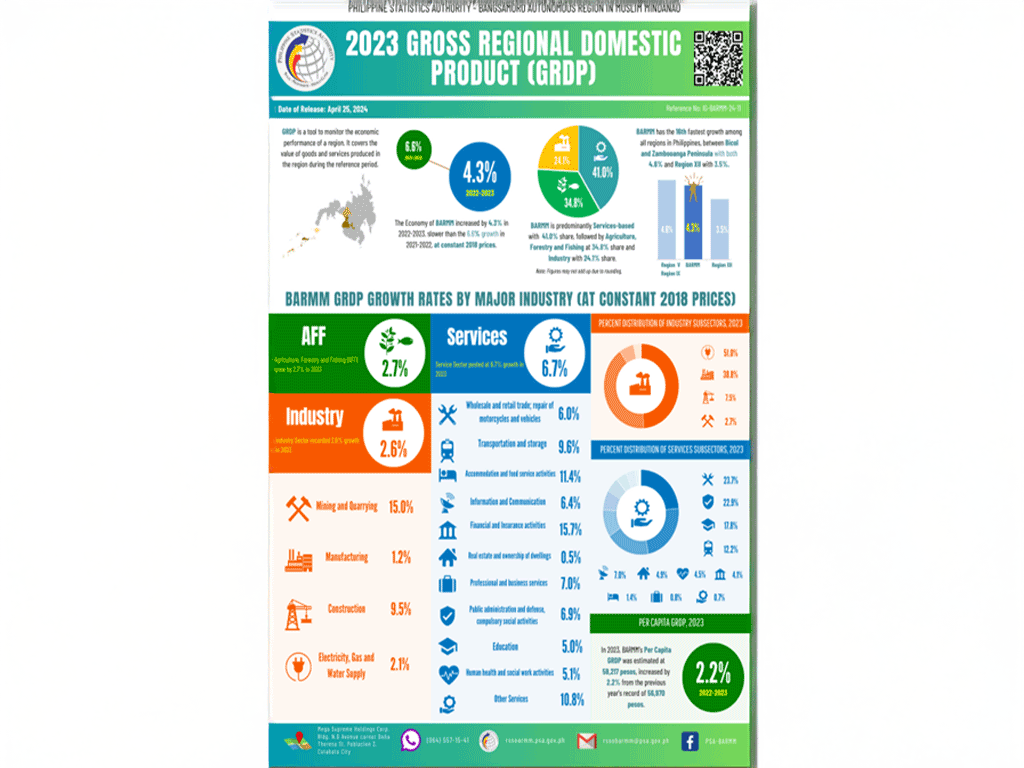

Based on statistical data, remarkable economic growth has been foreseen by the Philippine Statistics Authority, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, and the National Economic Development Authority from 2021 to date for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.

According to the forecast generated by the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) in 2016, the creation of the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region has socioeconomic implications for the region and the entire Mindanao area. With the expected improvement in peace and security, there will be an increase in economic activities and exploration of the untapped potentials of the region. Hence, NEDA suggested that the establishment of the BARMM would lead to the following directions: it will likely increase economic output, employment, and investments, thereby increasing the region’s and Mindanao’s overall contribution to the national output and development; as the security condition normalizes and economic activity resumes with vigor in the region, the intra- and interregional trade between and among the Mindanao regions, and with other regions in the country will be enhanced, in addition to foreign investors foreseen to inject fresh capital in the region; and, the sustained policies for peace and the continuing and committed investments in social, physical, economic, and cultural infrastructure will likely correct socioeconomic disparities in the region and the rest of Mindanao, raise human development, and reduce multidimensional poverty.

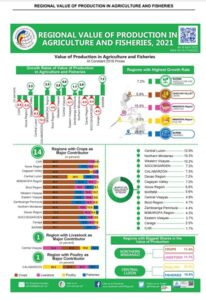

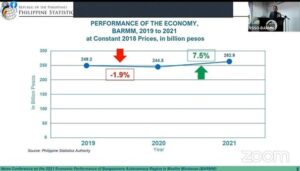

Roughly five years after the NEDA forecast had been published, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) reported that BARMM exhibited the second highest economic growth all over the country with 7.5 % economic growth from a negative 1.9% in 2019-2020. Industries that registered significant growth were: Human Health and Social Work Activities (22.2%), Mining and Quarrying (20.2%), Accommodation and Food Service Activities (17.9%), Construction (12.2%), and Financial and insurance activities (10.6%). All other industries also registered a positive growth. This was further supplemented by a growth rate of 7.2% in 2021, the highest growth in terms of agricultural and fisheries production among all the regions. This has been attributed to the growth in the fisheries sector’s production with a 22.8% rate, combined with agriculture.

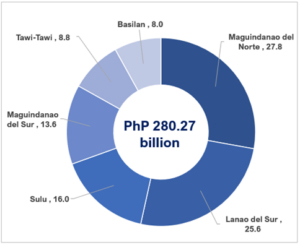

PSA Regional Director Engr. Akan Tula reported that from 2022, BARMM’s economy grew at 6.6% rate, slightly lower from 7.5% of 2021, but had increased in terms of per capita GRDP/GRDE to 4.5% from the previous year. Out of PhP 280.27 billion Gross Regional Domestic Product, Maguindanao del Norte leads the highest share to the GRDP with 27.8%, followed by Lanao del Sur with 25.6%, Sulu with 16%, Maguindanao del Sur with 13.6%, Tawi-Tawi with 8.8%, and Basilan with 8%. It has been reported by PSA that Agriculture, Hunting, Forestry, and Fisheries boomed to 3.5%, Industries spurred growth with 6.1%, and the Services Sector with 9.8% increase.

In 2023, BARMM recorded a 4.3% increase from that of 2022 or an equivalent of 11.9 billion increase in the region’s estimated Gross Domestic Product. Although lower than the previously recorded growth rate of 6.6% in 2022, the PSA believes that the 2023 growth rate is a strong indication of a resilient economy building in the region. On top of these developments is the indication of the transformation of the region’s economy. From being a largely agriculture and fisheries-based economy, BARMM has shifted into services, accounting for 2.7% of the 4.3% growth rate or P119.9 billion, subsequently followed by agriculture and industry with 1% or P101.8 billion each.

Sources:

Bangsamoro Government. 2024. BARMM’s 2023 economic performance surges by 4.3% in 2023–PSA. https://bangsamoro.gov.ph/news/latest-news/barmms-2023-economic-performance-surges-by-4-3-in-2023-psa/

Bangsamoro Government 2023. BARMM sets a record with the 10th fastest economic growth among all PH regions. https://bangsamoro.gov.ph/news/latest-news/barmm-sets-record-with-10th-fastest-economic-growth-among-all-ph-regions/

Bangsamoro Government. 2022. BARMM’s economy rises by 7.5% in 2021, sets record as 2nd fastest-growing region in PH. https://bangsamoro.gov.ph/news/latest-news/barmms-economy-rises-by-7-5-in-2021-sets-record-as-2nd-fastest-growing-region-in-ph/

Bangsamoro Planning and Development Authority. 2022. BARMM’s economic performance increases by 7.5% in 2021. https://bpda.bangsamoro.gov.ph/%f0%9d%90%81%f0%9d%90%80%f0%9d%90%91%f0%9d%90%8c%f0%9d%90%8c%f0%9d%90%ac-%f0%9d%90%9e%f0%9d%90%9c%f0%9d%90%a8%f0%9d%90%a7%f0%9d%90%a8%f0%9d%90%a6%f0%9d%90%a2%f0%9d%90%9c-%f0%9d%90%a9/

Bangsamoro Planning and Development Authority. 2023. BARMM’s economic performance grows by 6.6% in 2022. https://bpda.bangsamoro.gov.ph/%F0%9D%90%81%F0%9D%90%80%F0%9D%90%91%F0%9D%90%8C%F0%9D%90%8C%F0%9D%90%AC-%F0%9D%90%9E%F0%9D%90%9C%F0%9D%90%A8%F0%9D%90%A7%F0%9D%90%A8%F0%9D%90%A6%F0%9D%90%A2%F0%9D%90%9C-%F0%9D%90%A9-2/

National Economic Development Authority. 2016. Potential impacts of the creation of Bangsamoro on Mindanao regions. https://neda.gov.ph/potential-impacts-creation-bangsamoro-mindanao-regions/

Philippine Statistics Authority. BARMM Registered the Highest Growth in the Value of Production in Agriculture and Fisheries at 7.2 percent in 2021. https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/ppa-main/regional/node/167335

Philippine Statistics Authority. 2022. Maguindanao del Norte and Lanao del Sur Account for 53.4 Percent of the Economy of Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) in 2022. https://www.psa.gov.ph/content/maguindanao-del-norte-and-lanao-del-sur-account-534-percent-economy-bangsamoro-autonomous

Philippine Statistics Authority, 2022. Regional Value of Production in Agriculture and Fisheries, 2019-2021. Macroeconomic Accounts Service & Agricultural Accounts Division. https://psa.gov.ph/system/files/aad/Full%2520Report%252C%2520Regional%2520Value%2520of%2520Production%2520in%2520Agriculture%2520and%2520Fisheries%252C%25202019%2520to%25202021_0.pdf

Regional Statistics Service Office – BARMM. 2024. 2023 Gross Regional Domestic Product. https://rssobarmm.psa.gov.ph/system/files/infographics/IG-BARMM-24-11%202023%20GRDP.pdf

Read More

BBM Unity

2022

BBM Unity

President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s call for national unity led the two major Bangsamoro fronts, the MILF and MNLF to finally unite and work for MILF’s Moral Governance in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (BARMM).

“Unity,” this was the call of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. during the campaign period for the May 2022 elections. Despite MILF’s support for his opponent, former Vice President Leni Robredo, President Marcos Jr. supported the BARMM more inclusively by appointing the son and daughter of MNLF Chairman Nur Misuari. Another two sons of MNLF leaders belonging to the Executive 15 (EC15), another breakaway group, Muslimin Sema and Yusop Jikiri, became members of the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA) This initiative was welcomed by MILF Chairman Ahod ‘Murad’ Ebrahim. On September 15, 2022, MNLF Chairman Misuari and MILF Chairman Ebrahim were joined on stage by President Marcos Jr. during the opening ceremony of the BTA in Cotabato City.

The first attempt to unite both the MNLF and MILF was initiated by the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) from the time MILF founder Ustadz Salamat left the organization. It was repeated during the time of President Corazon Aquino and continued until the Ramos Administration. MNLF Chairman Misuari visited Ustadz Salamat in Camp Abubakar in 1997. The visit was accordingly to invite the Ustadz to rejoin the MNLF in the implementation of the final peace agreement. But MILF Chairman Ustadz Salamat decided to observe the situation first. Meanwhile, the Executive Fifteen (EC15), another MNLF faction mostly composed of senior leaders, held a unity talk with the MILF in Malaysia in August 2001.

It was only during the time of President Marcos Jr. that unity among the Bangsamoro fronts was achieved. However, on September 09, 2024, the Supreme Court approved Sulu’s previous petition to be excluded from the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). Nevertheless, the unity among the Moro fronts remained intact despite Sulu exit from the BARMM and the split between President Marcos Jr. and his Vice President Sarah Duterte. He also signed the law creating three additional Shari’a Judicial Districts and 12 Shari’a circuit courts nationwide.

Another milestone for Muslims’ history was when President Marcos Jr. signed Administrative Order No. 10 on Nov. 7, 2023, creating the steering committee tasked to facilitate the planning and implementation of programs, projects, and activities for the 650th-anniversary celebration of Philippine Muslim History and Heritage. This and the Integrated History Act will facilitate the bridging of religious and cultural gaps between the Muslims and their Christian brethren towards a harmonious relationship that is necessary to build a unified and strong nation where the Muslims can actively participate.

Sources:

https://ptvnews.ph/marcos-joins-misuari-ebrahim-during-bta-parliament-inauguration/

https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1213315

https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1973079/law-creating-more-sharia-court-judicial-districts

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TvOUfL-8ZDE

Read More