Maritime Trading

Age (Pre-Islamic)

BC

The Balobok Rock Shelter in Tawi-Tawi

The Obsidian Stone in Lanao

AD

800AD - 1365

Indian Link and Influences

1300

The 1365 Negarakertagama Manuscript

The Ancient Hindu Rulers of Sulu

The M'ranao Darangen

The Traditional Dances

The Maguindanao Pandita

1400

Poon Tao Kong in Sulu and Paduka Batara in China

The Kuntaw Martial Art

The Pagoda Style Mosques and the Chinese Contribution to the Spread of Islam

Traditional Dress Styles

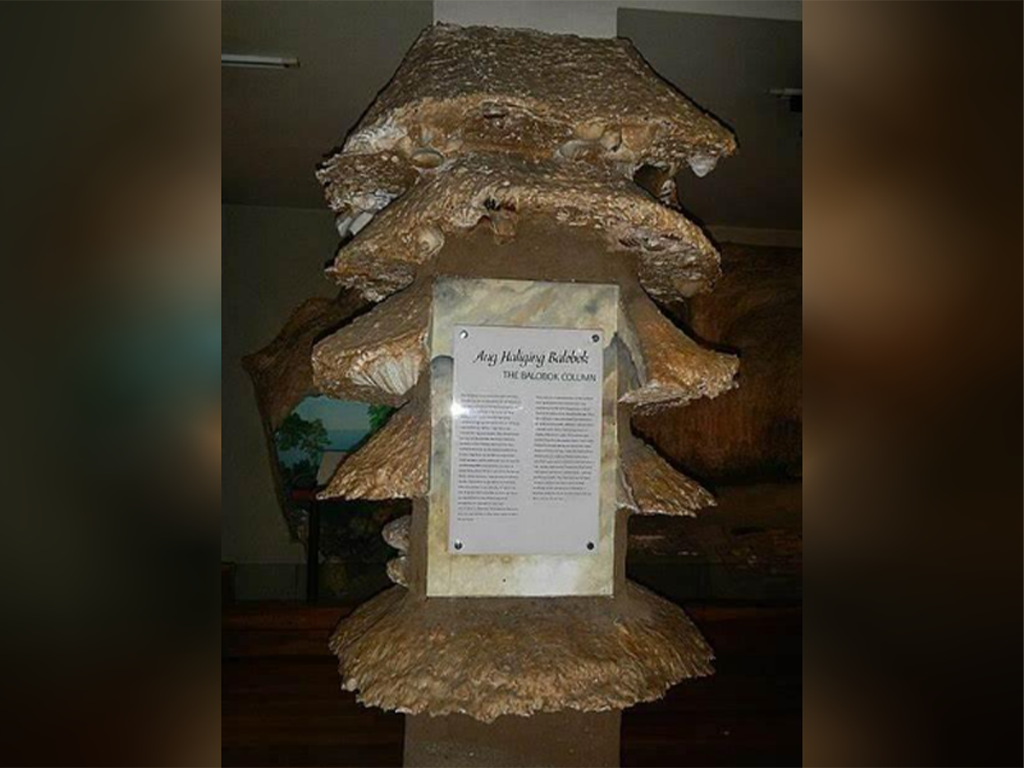

The Balobok Rock Shelter in Tawi-Tawi

The Balobok Rock Shelter in Tawi-Tawi

Balobok Archeological Site or Balobok Rock Shelter in Tawi-Tawi, a location of prehistoric habitation around 6810-3190 BCE (5760-5140 years ago), is considered as one of the earliest human settlement zones in Southeast Asia, yielding evidence of early human presence in the Sulu Archipelago.

The existence of the Balobok Rock Shelter in Bongao, Tawi-Tawi, Philippines, was reported in 1966. Following this discovery, excavation was initiated in late 1966 up to 1969, and a re-excavation in 1992 and 2007. Here, archeologists found polished shell adzes made from Tridacna gigas, flaked tools, polished stones, earthenware sherds with lime-impressed designs, and bone tools, demonstrating humans’ ability to create and use tools during that era. The recovery of these materials suggests that the site played a significant role in early people’s movements into the Southwest Pacific and the Pacific World.

Due to its historical relevance, Bangsamoro lawmakers lodged a bill declaring the Balobok Cave in Bongao, Tawi-Tawi, a heritage zone through the Bangsamoro Transition Authority Bill No. 197, also known as the “Balobok Cave Preservation Act of 2020.” With this, the Bangsamoro Commission for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (BCPCH) and the Environment Ministry would be responsible for administering the protection, development, and promotion of the Balobok Cave.

Sources:

Cayon, Manuel. 2023. ” Bangsamoro Parliament bill declares Balobok Cave in Bongao, Tawi-Tawi a heritage site – Radio Philippines Network. https://rpnradio.com/bangsamoro-parliament-bill-declares-balobok-cave-in-bongao-tawi-tawi-a-heritage-site/ businessmirror.com.ph. https://businessmirror.com.ph/2023/01/06/bangsamoro-parliament-bill-declares-balobok-cave-in-bongao-tawi-tawi-a-heritage-site/.

HistoryLearning.com. 2024. History Learning Balobok Archeological Site. https://historylearning.com/history-of-the-philippines/pre-history/balobok-archaeological-site/.

National Museum of the Philippines. 2022. Balobok Rockshelter. https://www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph/2022/06/28/balobok-rockshelter/

Read More

The Obsidian Stone in Lanao

The Obsidian Stone in Lanao

Obsidian, used as stone tools during the Terminal Pleistocene in Ille Cave (Palawan) and Bubog I (Ilin Island, Mindoro) discovered in Lanao del Sur, highlights the advanced maritime trade and mobility of the “Celebes Seafaring People” around 6000-5000 BP.

The obsidian found in Lanao del Sur is evidence of the active trade and mobility of ancient peoples, known as the “Celebes Seafaring People,” around the Celebes region circa 6000-5000 BP. These people had advanced boat-building and navigational skills, facilitating a vast maritime trading network. Chemical analysis indicates that obsidian in Lanao del Sur originated from Bukidnon, supporting the hypothesis of a maritime network that existed during the Neolithic Period. This period (6000-4000 BP) saw significant movement, agriculture, and pottery introduction, suggesting a shared cultural affiliation among Southeast Asia’s island communities. The “Celebes Seafaring People” hypothesis aligns with historical theories by Francisco Combes and Fay-Cooper Cole about migration patterns from Indonesia to Mindanao, suggesting a complex maritime exchange and migration network that needs further investigation.

Source:

Neri, Lee Anthony M, Juvanni A Caballero, Rona Catherin R Repancol, Ruben Claro A Reyes, and Jay Rone F Acasio. 2023. The Archaeology of Lanao del Sur: Probing the M’ranao-Chinese Relations Before 1898. Quezon City: University of the Philippines School of Archeology.

Read More

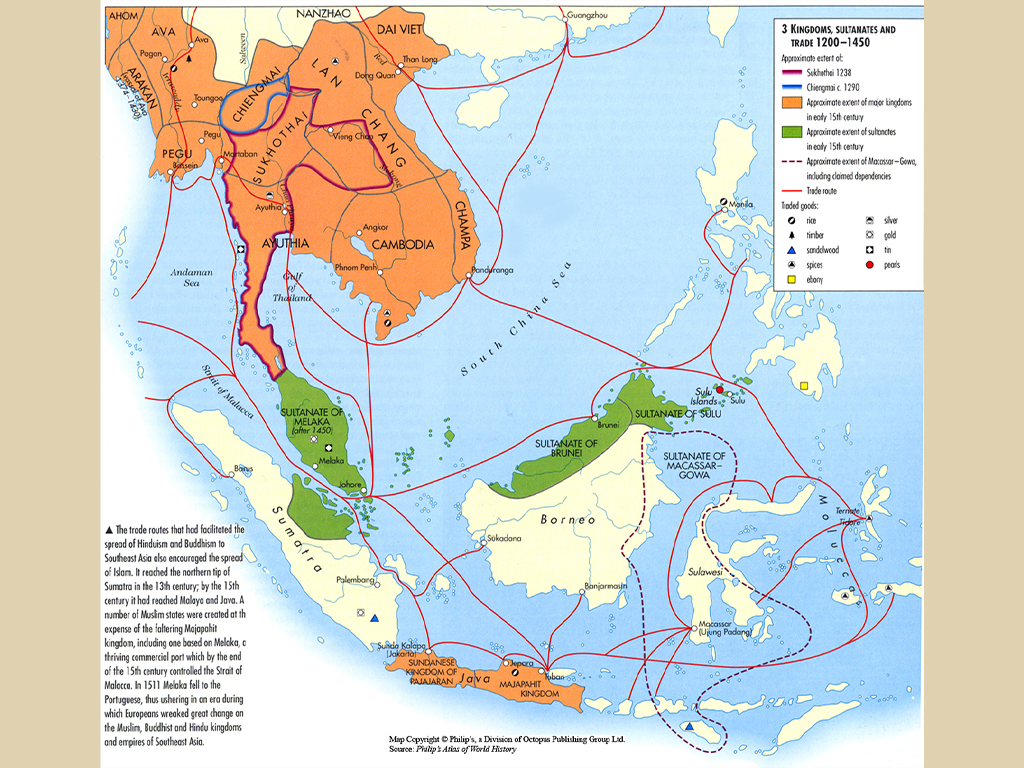

Indian Link and Influences

800AD - 1365

Indian Link and Influences

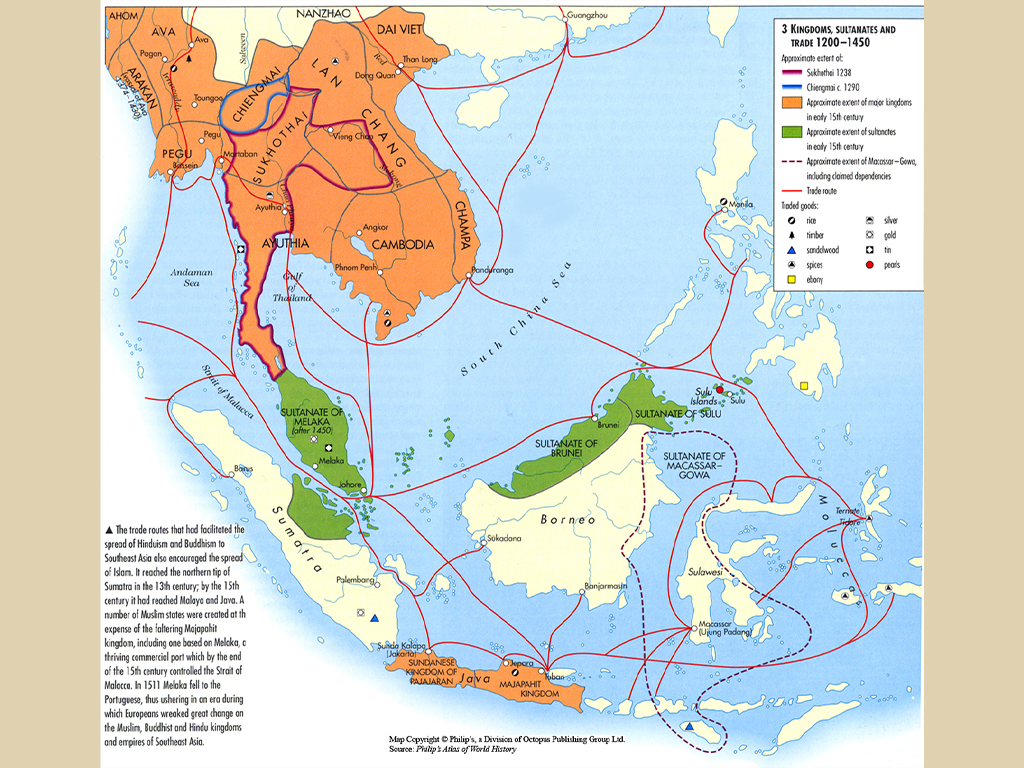

Before Islam arrived, Sulu and Mindanao were actively involved in the international sea trade, which facilitated the entry of Indian and Chinese traders and sages, who brought with them their culture, system of government, and religious ideas.

“The first Indian immigrants into the region seem to have been chiefly of the old Vedic faith, mixed with primitive nature and sun worship, although Buddhistic ideas became dominant in the early centuries of the Christian era. Indian traders and colonizers of these types seem to have entered the Philippines through Eastern and Northern Borneo. They continued to drift from about the twelfth and thirteenth century. The second wave of Indian influences with Brahmanic character entered the Philippines at the height of the Madjapahit Empire in the fourteenth century.”

Sources:

Beyer, Henry Otley. 1948. “Early History of Philippine Relations with Foreign Countries, Especially China,” Historical Introduction to E. Arsenio Manuel, Chinese Elements in the Tagalog Language. Manila: Filipiniana Publications.

Read More

The 1365 Negarakertagama Manuscript

The 1365 Negarakertagama Manuscript

The 1365 Negarakretagama Manuscript listed Sulu as part of the Madjapahit spheres of influence. From Sulu, Indians managed to penetrate mainland Mindanao.

The Negarakertagama is an Old Javanese eulogy written by a Buddhist monk, Empu Prapanca, around 1350-1389 for Hayam Wuruk, a Javanese king of the Majapahit. The manuscript talks about the history of the Hindu Empire, Majapahit (1293-1527 AD), and its dominion where Sulu was included. Based in Sumatra, the empire was founded by Kerjarajasa Jayawarddhana, locally known as Raden Wijawa, in 1293. Its peak of influence was reached during the reign of Hayam Wuruk.

Negarakertaga was named The Memory of the World by UNESCO in May 2008 and registered as a World Heritage in 2013.

Sources:

Prapanca, Mpu. 2017. Negarakertagama Kawi: In Kawi Script. USA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Read More

The Ancient Hindu Rulers of Sulu

The Ancient Hindu Rulers of Sulu

The first book on the History of Sulu written by a Lebanese American scholar Najeeb Saleeby whom the American government commissioned to study the Muslims in Sulu and Mindanao says that the names of Sulu’s ancient rulers, Jaimun Kulisa (God of Vedic Pantheon) and Indira (Goddess of Rain) Suga, were of Sanskrit origin.

At the height of the Srivijaya Empire in the ninth century, with Banjarmasin as its seat of power, they sent a colony to Sulu to drive out the Orang Dampuans (Champs) so they could control the pearl industry. To gain the trust of the Tausugs, they offered their princess to the local chief for marriage. The rajas (pre-Islamic rulers of Sulu) descended from this marriage alliance. According to the Sama people in this area, there was also a kingdom on a hill located on the eastern plains of Bud Tua in Dungan in Tawi-Tawi. Before the end of the tenth century, Buddhist Banjars introduced kingdoms under rajaship and datuship in Sulu and the Philippines.

Srivijaya was a Buddhist thalassocrat empire based in Sumatra that reigned from the seventh to the eleventh century.

Sources:

Ututalum, Sururul-Ain and Abdul-Karim Hedjazi. 2002. The Rise and Fall of the Sulu Islamic Empire (1675-1919). USA: Professional Press.

Kurais II, Muhammad. The History of Tawi-Tawi and Its People. 1979. Tawi-Tawi: Mindanao State University Sulu-College of Technology and Oceanography.

Hunt, J. 1967. Some Particulars Relating to Sulo in the Archipelago of Felicia. In Notices, of the Indian Archipelago and Adjacent Countries, edited by J. H. Moor. London: Cass Publishers.

Read More

The M'ranao Darangen

The M'ranao Darangen

Darangen is an ancient epic song of the Maranaos that reveals the traditional knowledge of Lanao during the pre-Islamic era.

With a total of 72,000 lines in 17 cycles, the Darangen celebrates episodes of M’ranao history, customary law, social and ethical behavior standards, aesthetic beauty, the tribulations of mythical heroes, and many other themes.

In 2005, the National Commission for Culture and the Arts declared it a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity,” They were inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity 2008.

The tales of Maharadia Lawana and Prince Bantugan, as depicted in the famous Singkil dance, are localized versions of the Ramayana, a popular epic of India. Similar Indian influence can also be found in the Maguindanao folktale Indapatra, Solayman, and the Sagayan Dance.

Sources:

Saber, Mamitua . 1961. Darangen: The Epic of the Maranaws. Philippine Sociological Review, January-April, Vol. 9, No. 1/2 (January- April 1961), pp. 42-46 Published by: Philippine Sociological Society. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43498156

Francisco, Juan. 1977. “Indian Imprint” in Filipino Heritage, vol.3. Quezon City: Lahing Pilipino Publishing Inc. p.576-79.

https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/darangen-epic-of-the-maranao-people-of-lake-lanao-00159

Read More

The Traditional Dances

The Traditional Dances

Pangalay and Igal of the Tausug and Sama, Singkil of the M’ranao, and Sagayan of the Maguindanao are celebrated traditional dances of Indian influence via the Malay world.

The Pangalay dance of the Tausug, which is called Igal among the Sama of Tawi-Tawi, is meditation in motion. The various and endless movements of the hands derived from the stillness of the mind reflect how God created the world of nature in various forms. Singkil of the M’ranao and Sagayan of Maguindanaon are royal dances derived from an episode of the Darangen epic of Bantugan, a M’ranao prince. Singkil was listed as one of the Bayanihan’s Signature Dances of the Philippines. Sagayan dance among the Maguindanaon is also performed to welcome good fortune and drive away bad spirits.

Sources:

Namiki, Kanami. 2011. “Hybridity and National Identity: Different Perspectives of Two National Folk Dance Companies in the Philippines.” Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspective on Asia. Vol. 47. https://www.asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-47-2011/namiki.pdf

Kasim, Osmeña M. (2021. “Appreciation Level on Maguindanaon Dances and their Cultural Presentation.” International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR) Volume 59, No 1, pp 188-201.

Read More

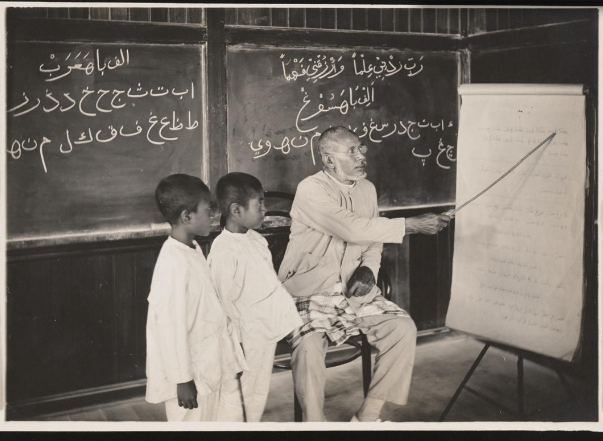

The Maguindanao Pandita

The Maguindanao Pandita

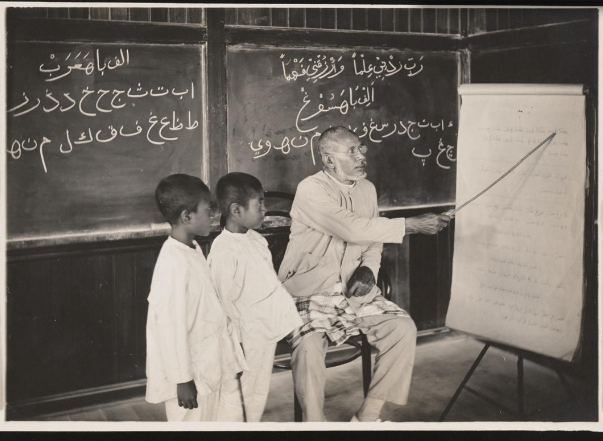

Pandita, a Sanskrit-based word referring to a learned man, especially among the Maguindanaon, was the most important figure in Philippine Muslim Society.

Indian sages introduced a universalistic tradition that elevated the religious understanding of the natives and prepared them for the arrival of Islam. Some religious words like agama (religion), puasa (abstinence), narka (hell), surga’ (heaven), pahala (reward), bartapa/balatupa (seclusion in the mountain), and many others which are of Sanskrit origin are being used by all Muslims in Mindanao and Sulu until today.

Panditas who were learned in religion and spirituality, were responsible for preserving Islam until the American occupation. American authorities reported that pandita schools operating in Mindanao were a major hindrance to the introduction of Western secular education. The panditas were also military opponents of Western colonial rule since the Spanish period. They not only encouraged the natives to wage jihad against the conquerors but also participated in the military defense of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago.

Sources:

Absari, Darwin J. PagTuhan: The Tausug Spiritual Tradition. 2021. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Baldoza, Jonathan Victor. The Panditas of the Philippines, 17th – Early 20th Centuries. Archipel [Online], 103 | 2022, Online since 30 August 2022, accessed on 12 September 2022. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/archipel/2969

Gowing, Peter Gordon. 1983. Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Milligan, Jeffrey Ayala. 2020. Islamic Identity, Postcoloniality, and Educational Policy: Schooling and Ethno-Religious Conflict in the Southern Philippines. Singapore: Springer Nature.

Read More

Poon Tao Kong in Sulu and Paduka Batara in China

Poon Tao Kong in Sulu and Paduka Batara in China

Two important historical landmarks that keep the Sulu and Mindanao link with China alive. The tomb of Poon Tao Kong in Sulu and the shrine of Sulu ruler Paduka Batara in China

In 1405, Chinese Emperor Yongle dispatched his Muslim Admiral Cheng Ho to ‘Western Ocean’ (the Pacific and Indian Oceans) to establish diplomatic ties and promote Chinese culture and trade with other countries. From 1405-1433, Admiral Cheng Ho led seven expeditions that reached as far as Africa and Southeast Asia. Sometime in 1410, one of Cheng Ho’s high-ranking officers, Admiral Pei Pei Hsien visited and stayed for two years in Sulu where he eventually died. The Tausug call him Poon Tao Kong (the Honorable Fountainhead) for constructing an artesian well in Maubuh which became the source of water of the people in the area. His grave in Indanan, three kilometers south of Jolo town is being protected by the people until the present.

The visit of Admiral Pei Pei Hsien inspired the three rulers, Paduka Batara, Kamaluddin, and Paduka Brabu to pay tribute to China in 1417. On their way home, Paduka Batara got sick and eventually died. He was buried in Dezhou, Shandong province of China. Emperor Yongle instructed his artisans and sculptors to construct his shrine. His two sons, Wenhala and Andulu who stayed there, got married and became naturalized. Their descendants are now scattered all over China. In 1987, a film ‘Hari sa Hari, Lahi sa Lahi’ depicting this journey was directed and released by famous Filipino and Chinese filmmakers.

This tribute mission brought Mindanao and Sulu to an intimate and intensive trade with China. In December of the same year, Chinese Emperor Yongle dispatched High Commissioner Chang Ch’ien to the Philippines to bring Kumalalang, Mindanao, into line. In 1420, King Kanlai Ipentun of Kumalalang, Mindanao, paid tribute to China. More and more Chinese came to the Sulu Archipelago and Mindanao to live with the natives and found a second home there. At challenging times, Sulu and Mindanao became their refuge. For example, in 1758, thousands of Chinese fled to Sulu to escape persecution by the Spaniards. Dulawan in Maguindanao was the center of trade from which they penetrated Lanao’s heartland. Chinese artifacts recently found in Lanao suggest their presence in the area.

Chinese long stays in the Sulu Archipelago and Mindanao also resulted in cultural and philosophical exchanges. Many of their legacies, such as dress style, martial arts, culinary habits, and wedding and burial rights, continue to survive among the Muslims in Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago.

Sources:

Scott, William Henry. 1989. Filipinos in China before 1500. China Studies Program. Manila: De La Salle University.

Tan Ta Sen. 2009. Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies Publishing.

Absari, Darwin J. 2023. Sulu-China History from Pre-Islamic to Spanish Era. Chinese Study Journal Vol. 17, p.227-242. https://www.chinesestudiesjournal.org/volumes/volume-17-2023/sulu-china-history-from-pre-islamic-to-spanish-era

Chu, Richard T. (Ed). 2015. More Tsinoy Than We Admit: Chinese-Filipino Interactions Over the Centuries. Quezon City: Vival Foundation.

Read More

The Kuntaw Martial Art

The Kuntaw Martial Art

Kuntaw is a celebrated martial art practiced by Muslims across the Sulu archipelago and Mindanao.

One of the enduring legacies of Chinese in the Sulu archipelago and Mindanao is the Kuntaw martial art. The word kuntaw is derived from Chinese words Kung (skill) of Kung Fu and Tao (the Way) of Taoism. It is a localized version of the Chinese martial art Tai Chi.

Source:

Absari, Darwin J. 2021. PagTuhan: The Tausug Spiritual Tradition. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Read More

The Pagoda Style Mosques and the Chinese Contribution to the Spread of Islam

The Pagoda Style Mosques and the Chinese Contribution to the Spread of Islam

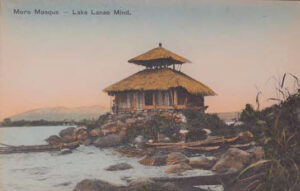

Chinese influence is also visible in the old pagoda-style mosques in Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago.

Chinese has also participated in the spread of Islam to Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago. In Sulu, a certain Makhdum Aminulla, who possibly arrived after Karimul Makhdum, is said to have been accompanied by a Chinese Muslim Huy-Huy (Hue). The design of the original pillars in Tubig Indangan, Simunul in Tawi-Tawi is believed to have been carved by a Chinese Muslim. The design of old mosques in Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago as well as those of other countries in Southeast Asia is inspired by the Chinese pagoda.

Sources:

Majul, César Adib. 1999. Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Ta Sen, Tan. 2009. Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Read More

Traditional Dress Styles

Traditional Dress Styles

The Chinese has also influenced the traditional dress styles of the Muslims in Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago.

Another Chinese influence among the Muslims in the Philippines is their traditional dress style especially the preference for yellow color for the royalty dress of the Tausug, Maguindanaon, and M’ranao. Chinese remains famous in many of the traditional dresses of Muslims. In Sulu, the word Dasu Lannang (Chinese silk) is still used today.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar Adib. 1977. “Celestial Traders in Sulu.” In The Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation, vol.3, edited by Alfredo R. Roces, 592. Manila: Lahing Pilipino Publication.

Absari, Darwin J. “Lannang Sug: The Long History of Chinese in Sulu.” Research funded by the Ateneo Confucius Institute. Forthcoming.

Read More