Encounters with Western

Colonial Powers

1400

1493

The Papal Bull

1500

1571

The Fall of Islamic Manila to Legazpi and the Birth of Moro Identity

1596

Figueroa Campaign Against Sulu and Maguindanao

1600

1600 - 1900

Sultanato ng Maguindanao at Pat a Pongampong ng Ranao

1603

Moro-Filipinos Alliance Against Spain

1617

Datu Aceh: The Famed Warrior

1619-1671

Sultan Kudarat (1619-1671): The Most Powerful Maguindanao Sultan

1627

Raja Bongsu: The Beginning of an Epic Battle

1637

Sultan Kudarat and the Battle of Ramitan

1638

The Epic Battle: Four-Month Siege of Jolo

1700

1735-1775

The Intriguing Story of Sulu Sultan ‘Azim ud-Din

1753

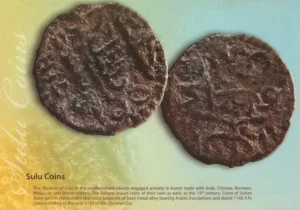

Sultan Mu‘izz ud-Din Sought Support from Chinese Emperor Against Spaniards

1791-1808

Further Expansion of Sulu Sultanate’s Dominion

1800

1850

Urbiztondo and the Friendship Treaty With Sulu

1876

The Fall of Jolo

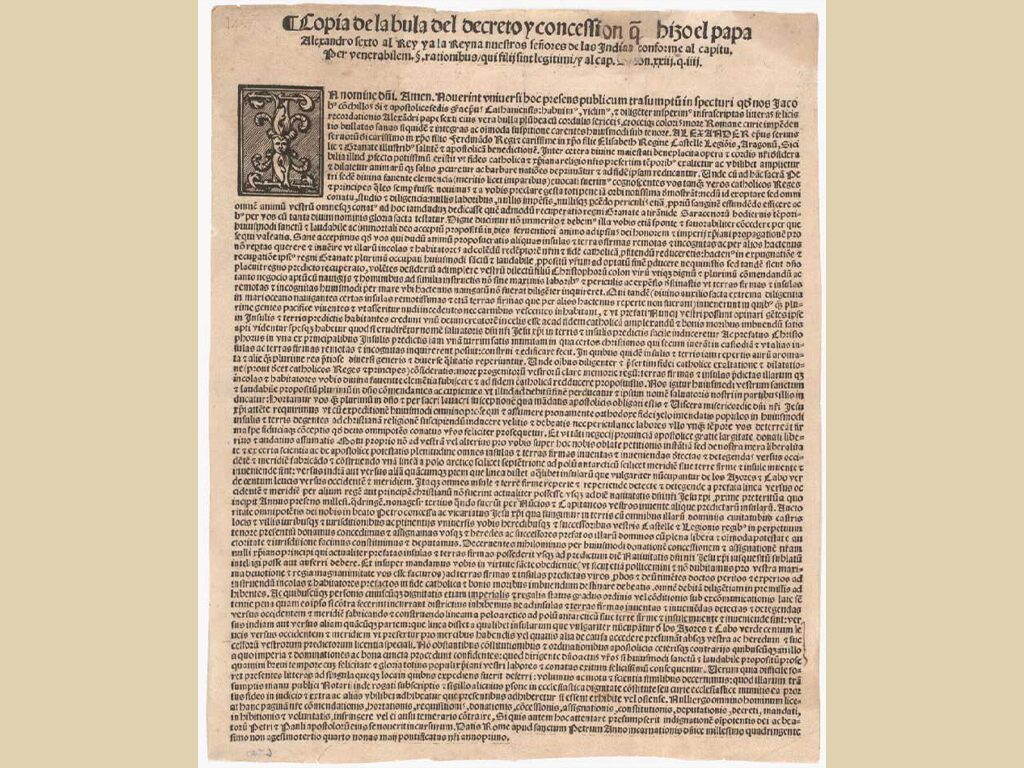

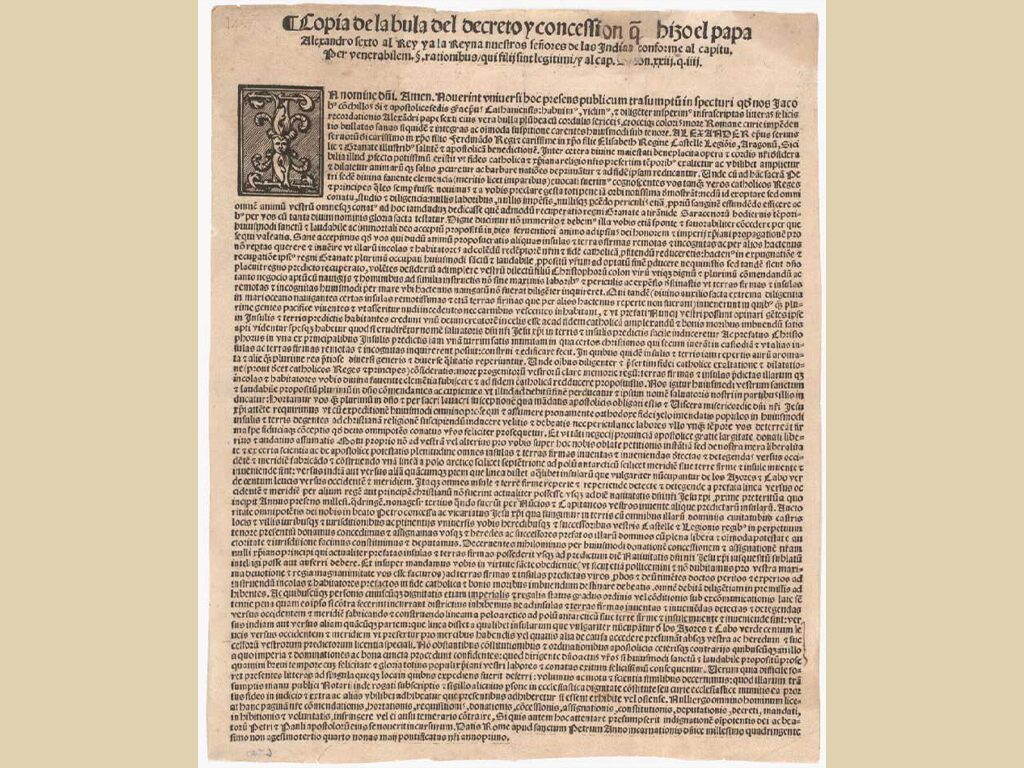

The Papal Bull

1493

The Papal Bull

The Papal Bull of 1493 issued by Pope Alexander VI was a document that authorized the Spanish government to colonize, enslave and spread Catholicism using force if necessary. It was here when the Philippines was subjugated and brought under Spanish Crown, while the Muslims in the south fought to remain free. Excerpt from the English Translation of the 1493 Papal Bull Wherefore, as becomes Catholic kings and princes, after earnest consideration of all matters, especially of the rise and spread of the Catholic faith, as was the fashion of your ancestors, kings of renowned memory, you have purposed with the... Read More

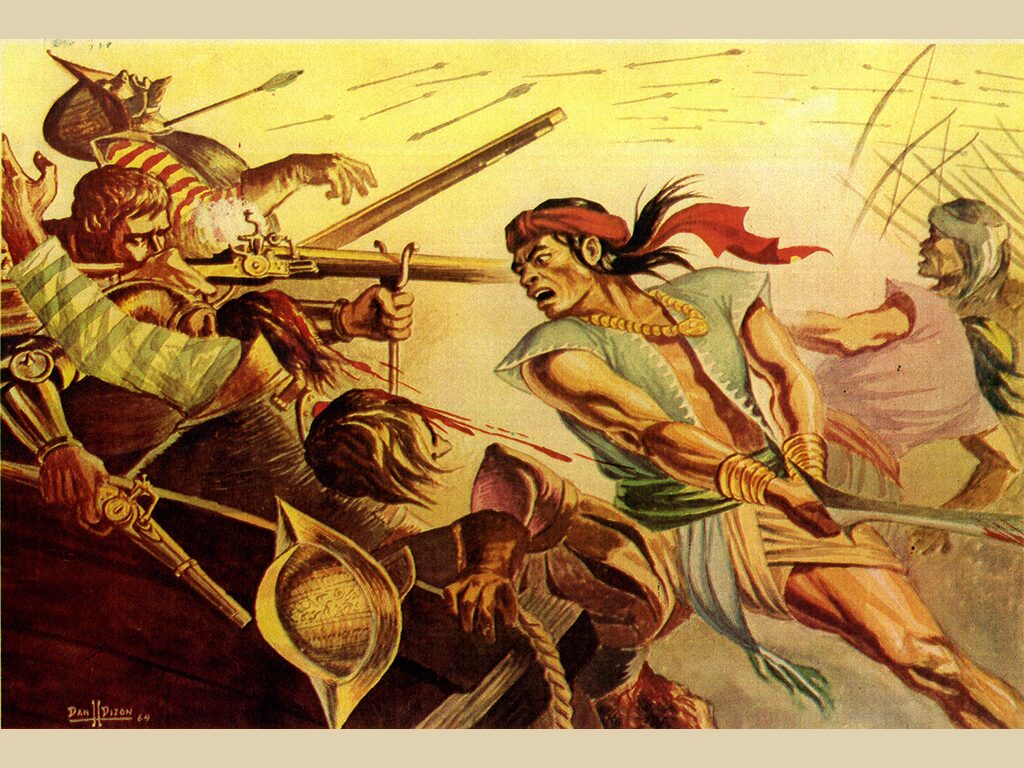

The Fall of Islamic Manila to Legazpi and the Birth of Moro Identity

1571

The Fall of Islamic Manila to Legazpi and the Birth of Moro Identity

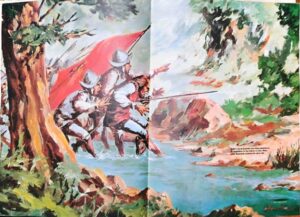

Crossing the Pacific into the Philippines, the Spaniards once again encountered Muslims in Manila whom they called Moros, a name derived from Moors, their traditional enemies in Spain. Despite having a different history and with no previous antagonistic relationship between the Muslims and Catholics, Spaniards looked at the war against the Moros as a continuation of the reconquest. With the help of the Christianized natives from the Visayas, two major armed resistances fell and Catholicism rapidly spread to almost the entire Luzon and Visayas areas.

The first Spanish expedition sent to the Far East was led by a Portuguese, Ferdinand Magellan, who arrived in the Visayas area in 1521. Although he successfully converted the natives to Catholicism, he was killed in Mactan by Lapu-Lapu’s men who were believed to be Muslims.

After Magellan, King Charles sent three more expeditions; in 1525, 1526, and 1527 but all ended in failure. Frustrated and bankrupt, he agreed to sign the Treaty of Zaragosa with Portugal in 1529 which defined the areas of influence of both countries in Asia. A demarcation line at 297.5 leagues east of the Moluccas was drawn. All lands west of the line including Moluccas and the Philippines belonged to Portugal. To the east were for Spain.

Despite the treaty, in 1542, King Charles I sent an expedition headed by Lopez de Villalobos to establish a permanent settlement in the Philippines. After a year, the expedition arrived in the island of Sarangani, south of Mindanao. But hunger and stiff hostilities of the Muslims forced Villalobos to abandon the expedition. On their way to Moluccas where they were imprisoned by the Portuguese, they passed by Samar-Leyte. Bernard de la Torre, one of the crews, named the island Las Islas Filipinas or the Philippine Islands in honor of the Spanish crowned prince, Prince Philip II. The name was later applied to the entire archipelago and was anglicized by the Americans to its present name, Philippines.

In 1556, Philip II ascended to the throne and made it an official policy to colonize the Philippines. On April 27, 1565, Spanish expedition under Miguel Lopez de Legazpi arrived in Panay. In five years, Legazpi has subjugated Panay and areas near Cebu, and destroyed the Muslim fortified outpost in Mindoro. Bearing the hatred for their Muslim enemies in Spain and the same people who stood as the main obstacle to their economic ambition in the Philippines, King Phillip II affirmed this policy in his written instruction to Miguel Lopez de Legazpi in 1566, which partly reads, “We give you permission to make such Moros slaves and to seize their property.” After acquiring the help of Visayan natives, Legazpi sent Martin de Goiti with 120 Spanish soldiers and hundreds of Visayan natives in early May of 1570 to deal with Raja Sulayman in Manila.

After the siege of Manila, Goiti returned to Panay with some booties. A year later, on May 03, 1571, Spaniards led by Legazpi himself, with 250 harquebusiers and 600 Visayan natives, returned to finally take Manila permanently for their economic ambition in the country. But another organized resistance was launched by a young Macabebe chief from Pampanga, Tariq Sulayman. His death, however, led to the defeat of his entire 2,000 warriors.

With the defeat of Raja Sulayman and the young Macabebe chief, all resistance to Spanish rule in Luzon and Visayas, including the aborted Magat Salamat conspiracy in Tondo in 1578, were suppressed by the Spaniards. In a span of eleven years, almost the entire Luzon and Visayas were reduced into vassalage to the Spanish crown and subjected to Spanish control. But the Moros in Sulu and Mindanao whom the Spaniards called Moros, remained free, and the Spaniards would have yet to deal with them.

Legazpi’s meeting with Muslims in Manila and the entire Spanish military campaign in Sulu and Mindanao was described by a Spanish author in 1884:

“When they landed in Manila, soldiers of Legazpi found on the same site of the present Fort Santiago, key to the capital of Manila, a powerful Muslim principality under Raja Matanda… who… reigned in company with a nephew, Raja Suliman, the one who favored the policy of war… Under the walls of this port, a historical event, little appreciated but which influenced our conquest, took place. It was there for the first time since the conquest of Granada that the Spaniards once more stood face to face with the standards of the Prophet, both meeting after circling the globe from opposite directions. As was inevitable, they met at the walls under artillery fire; and they continue to do so in Jolo, fighting a battle that began on the borders of Guadalete. And as if nothing should detract from that continuity, Legazpi called them Moros, a name they keep up to this time and which, regardless of having in common with the Mauritanians, signifies a community of religion shared with the Spanish Arabs.”

Sources:

Jubair, Salah. 1999. Bangsamoro: A Nation Under Endless Tyranny. Kuala Lumpur: IQ Marin.

Alfonso, Ian Christopher B. 2016. The Nameless Hero. Pampanga: Holy Angels University Press.

Majul, Cesar A. 1999. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Wadi, Julkipli M.2009. Rajah Sulayman, Spain and the transformation of the Islamic Manila. Quezon City: RAIS Publication.

Read More

Figueroa Campaign Against Sulu and Maguindanao

1596

Figueroa Campaign Against Sulu and Maguindanao

After the fall of Manila and the establishment of a Spanish colony in Luzon, the Spanish conquistador Don Ésteban Rodriguez de Figueroa embarked on a campaign to conquer the Muslims of Sulu and Maguindanao from April 1-25, 1596. While he succeeded in extracting tribute from the Sulu sultan, he was killed in Maguindanao.

Before conquering the Muslims in Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago, Spaniards first attacked Brunei thinking that defeating Brunei would weaken Sulu and Mindanao and eliminate their commercial rival in the Philippines. Brunei royalty was intimately connected to the Muslim rulers in Manila and Sulu and Bornean traders were business partners of the Muslims in the country. This motive was underscored in the letter sent by Spanish officials in Cebu to Spain, thus:

“We beseech his majesty, and your highness in his royal name, that, inasmuch as the said Moros and others take all the gold, pearls, jewels precious stones and other things of which we have no information-thus injuring the natives, both by giving us no opportunity to plant our holy faith among them, and by taking the said gold, they should, if they continue the said trade, lose their property and be made slaves, for they preach the doctrine of Mahomet.”

With the permission of the Spanish King, Spaniards attacked and defeated Brunei in 1578. Governor Francis de Sande then instructed Captain Esteban Rodriguez de Figueroa to go to Sulu to demand tribute and proceed to Maguindanao to reduce their leaders into vassalage, stop admitting Muslim preachers, and convert to Christianity. Captain Roriguez’s victory over Sulu raja in two minor engagements resulted in the payment of some amount by the Sulu sultan which was considered a tribute by the Spaniards. But the Spaniards were not lucky in Maguindanao.

In 1591, the Spanish authorities in Manila fomented a plan to colonize the rulers of Maguindanao. Governor-General Francisco de Sande entered into an agreement with Don Èsteban Rodriguez de Figueroa to launch an expedition in Mindanao and establish a colony at his own expense. In return, Figueroa was to be designated as governor of Mindanao for life and the position shall be inherited by his heirs.

On April 1, 1596, Figueroa was able to mobilize fifty vessels comprising of 214 Spaniards and 1,500 native allies. After traveling for about three weeks, the expeditionary forces arrived in the mouth of Pulangi and the Maguindanaon rulers withdrew to the interior avoiding a direct confrontation. Upon their arrival, the Spaniards established a fort in Tampakan between Maguindanao and Buayan.

On April 25, five days after his arrival, while on his way to Buayan to conquer Rajah Silongan, he was ambushed by Datu Ubal, a relative of Silongan. Datu Ubal landed a decisive blow against him on the head and as a result, he died a few hours later.

With the death of Figueroa, Juan de Xara took over the fort and its operations. The following year, Juan Ronquillo would be sent to Mindanao to manage the affairs of the camp and direct the operations under the auspices of the Spanish authorities in Manila. While Ronquillo was able to defend the camp after a series of skirmishes between the Spaniards and the Moros, he would be forced to abandon the fort on account of difficulties in communications, inadequate supplies, and losses in terms of manpower. The Spaniards would later on decide to establish another fort in La Caldera, a few miles from Zamboanga.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar Adib. 1999. Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Press.

Mastura, Datu Michael O. 2022. Rulers of Magindanao in Modern History, 1515-1903: Continuity and Change in a Traditional Realm in the Southern Philippines. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

de Morga, Antonio. 1890. Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, annotated by Jose Rizal. Paris: Libreria de Garnier Hermanos.

Read More

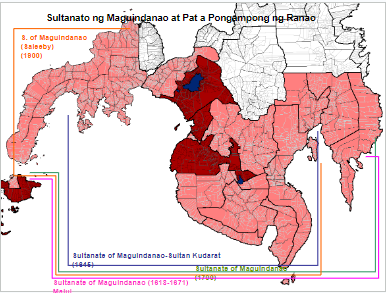

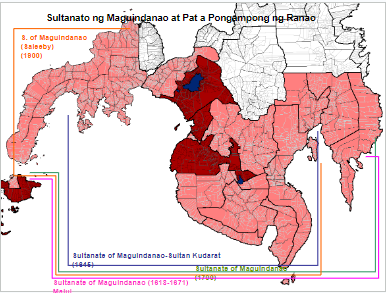

Sultanato ng Maguindanao at Pat a Pongampong ng Ranao

1600 - 1900

Sultanato ng Maguindanao at Pat a Pongampong ng Ranao

“In the fullness of its glory, the sultan of Maguindanao ruled over the whole southern coast of Mindanao from Point Tugubum (Tagum?), east of Mati, to Zamboanga, and beyond this latter point to the outskirts of Dapitan. All the pagan tribes living around the Gulf of Davao and in the Sarangani country, and all the Subanos west of Tukuran and Dapitan submitted to his power and paid him tribute. In the Upper Rio Grande Valley the power of the rajas of Bwayan was felt and respected as far as the watershed of the Cagayan Valley on the north and the... Read More

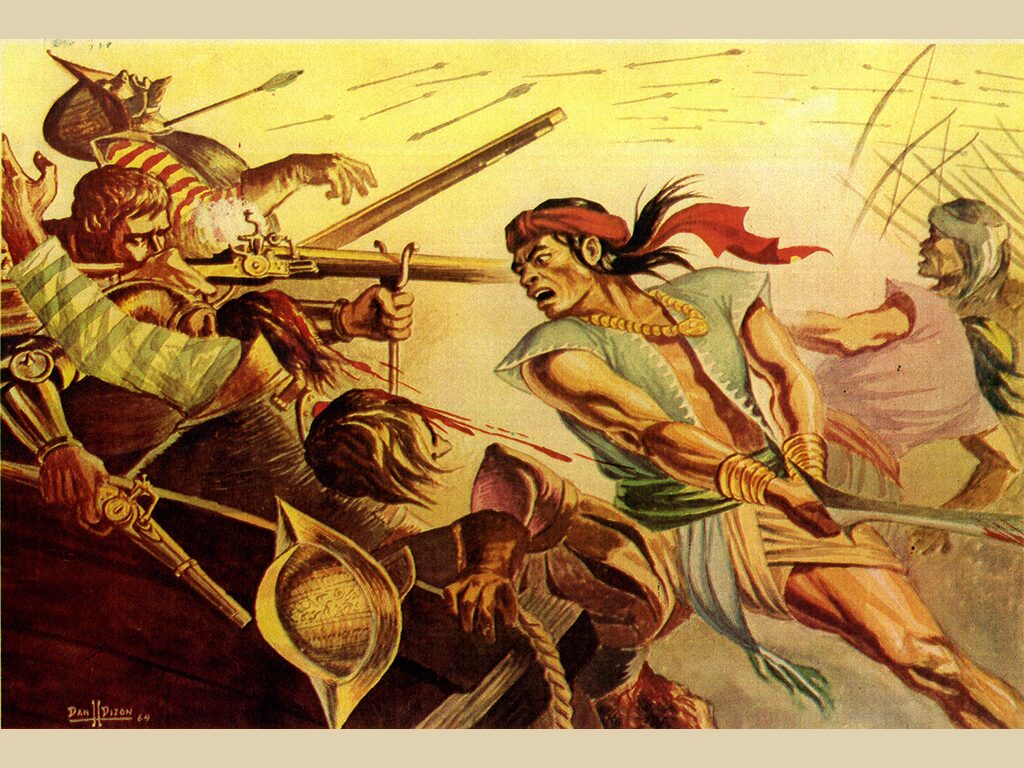

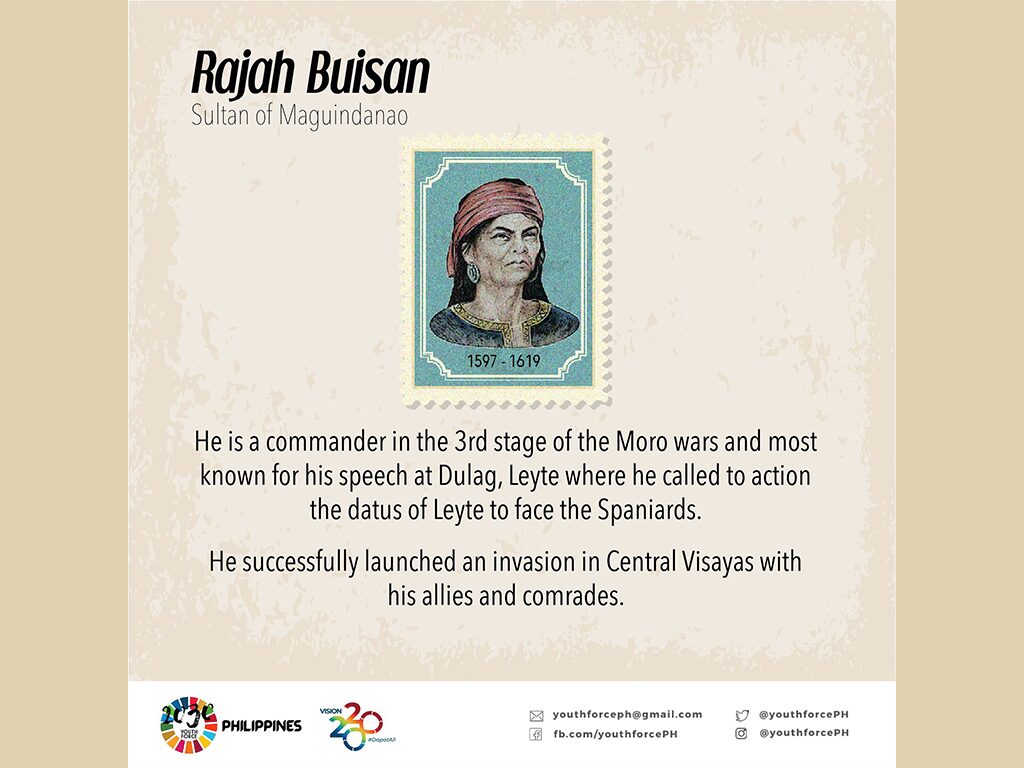

Moro-Filipinos Alliance Against Spain

1603

Moro-Filipinos Alliance Against Spain

On October 29, 1603, Raja Buisan of Maguindanao forged alliance with leaders of Dulag, Leyte, to throw off the Spaniards in the country. However, the alliance did not last when the Spaniards defeated the Ternate, Maguindanao’s strong ally.

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=2433473653421589&id=804364539665850&set=a.804853572950280&locale=bg_BG

With the support from Sangil and Ternate, Raja Buisan of Maguindanao, attacked the town of Dulag in Leyte on October 29, 1603. With him were more than fifty war vessels and about a thousand men. He burned the church and the town, took a few hundred captives, and amassed a large booty. After leaving word that he wanted to talk with the datus of Leyte upon his return to Dulag in a a span of one week, he sailed away to destroy other nearby ports and put their churches to the torch. His attack was so devastating that it made difficult for the Spanish garrison in the Visayas and Calamianes to cope with the situation. Even non-Muslims in Mindanao took advantage of the situation by raiding islands in eastern Visayas.

When he returned to Dulag, the Leyte datus were waiting for him. He gave back what he took from them and convinced them to make an alliance against the Spaniards. “The Spaniards,” he said, “were only a handful, nor were they as invincible as they made themselves out to be. Let the people of Leyte be resolute; let them prepare to rise as one man.” The meeting ended with a blood compact to formalize their alliance.

Spain’s response was to create dissension by concluding an agreement with his rival Raja Sirungan of Buayan on September 06, 1605, recognizing him as the paramount chief of Maguindanao in return for his allegiance to Spain. Raja Sirungan also had to stop all incursions into Spanish territories. This agreement was also to prevent possible attacks of the Muslims on Christian settlements as Spanish governor Pedro Bravo de Acuña was granted permission to fight the Dutch and conquer Moluccas in 1604.

Spanish Victory in Moluccas and Ternate compelled both Raja Buisan and Raja Sirungan to write the Spanish governor on July 22, 1604, to ask forgiveness for their previous alliance with Ternate and appealed to Spain not to retaliate.

Source:

Majul, Cesar A. 1999. Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Read More

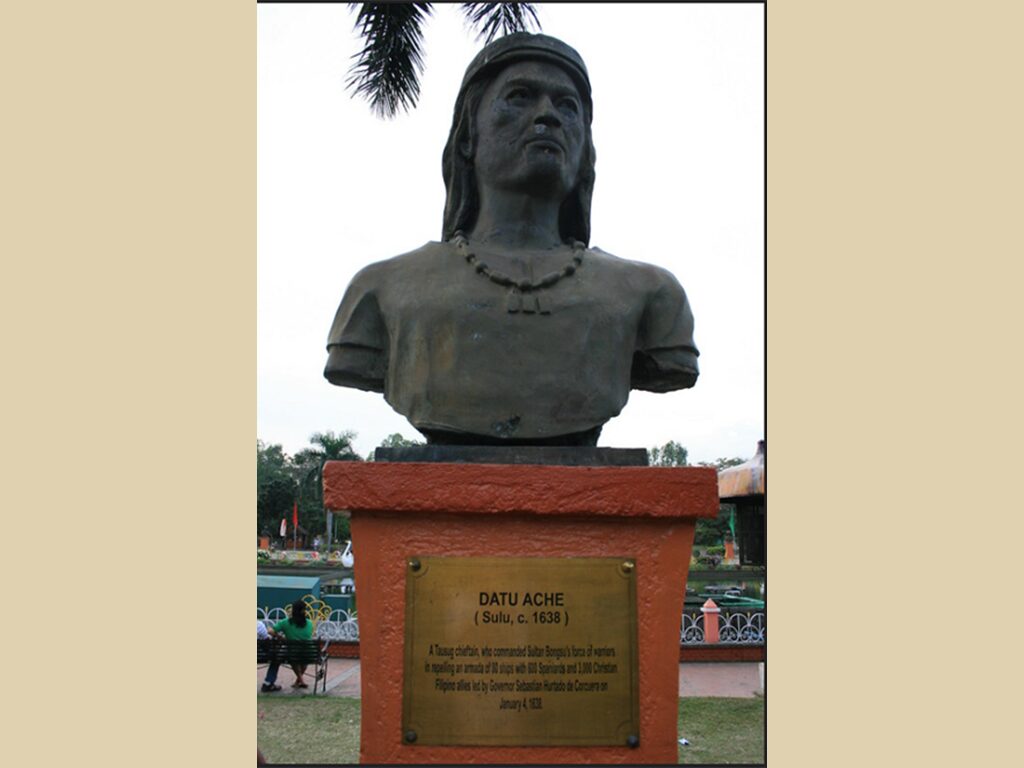

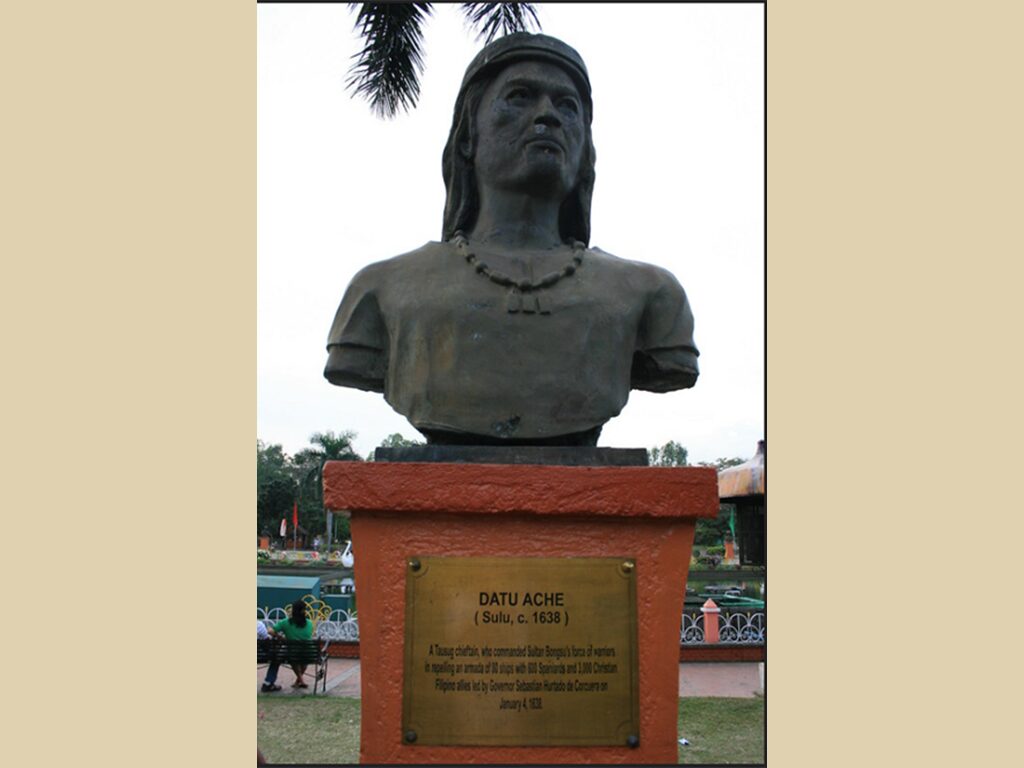

Datu Aceh: The Famed Warrior

1617

Datu Aceh: The Famed Warrior

Datu Ache was a mentor of Sulu’s Sultan Raja Bongsu and the defender of Sulu. His bravery compelled the Spanish government to bring its wrath to Sulu.

Datu Ache was an experienced fighter in Brunei when he was assigned as a mentor and guide by the Brunei sultan to the young ruler of Sulu, Raja Bongsu. His political career began when he attacked Camarines.

In 1614, Datu Ache and Raja Bongsu met with Dutch Admiral Laurens Reael to make a pact against the Spaniards. The Dutch admiral viewed this as a peculiar negotiation from the young “King of Sulu” since it did not agree with the Twelve-Year Truce. At first, this negotiation did not materialize until 1616.

On the 1st of November 1616, a fleet of 10 Dutch galleons sailed to Manila Bay and remained in the region until it was defeated and destroyed by the Spanish fleet in April 1617. While the Spaniards were preoccupied with the attacks of the Dutch, Datu Ache took this opportunity to raid the Pantao shipyard in Camarines where several large vessels were being built. Thirty Spaniards were killed, and others were captured as slaves,

After destroying the ships and stripping the vessel’s weapons, they overran several of the Visayan islands on their way home. In Leyte, he captured the widely known holy man, Fr. Juan Domingo Valencia S.J. He brought Fr. Juan to Jolo and treated him well. The Jesuits tried to ransom him, but he died and was buried in Jolo as he was already old and frail. After this, the Spaniards regarded the Tausug as the “most dangerous enemies.”

In 1624, Raja Bongsu sent Datu Ache to Manila to negotiate a truce with the Spaniards to protect the wealthy trade in Sulu. However, on his return journey to Sulu the following year, a Spanish patrol seized Datu Ache’s ship, imprisoned him in Manila, and confiscated his goods. When the news reached the authorities, they immediately released Datu Ache with profuse apologies, and his goods were restored. The datu claimed that three large pearls of great value were not returned to him, thus he left resentfully. He even returned to Manila to secure his pearls, but he was unsuccessful.

There were other Tausug traders who were robbed by a Spanish patrol. Fray Medina even concluded this action as an injustice against the Tausug. Raja Bongsu did not like what happened and plotted a revenge attack on the Spaniards.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar A. 1999. Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Nicholl, Robert. 1991. Raja Bongsu of Sulu – A Brunei Hero in His Times. Council of the Malaysian Branch of Royal Asiatic Society.

Read More

Sultan Kudarat (1619-1671): The Most Powerful Maguindanao Sultan

1619-1671

Sultan Kudarat (1619-1671): The Most Powerful Maguindanao Sultan

The height of Maguindanao Sultanate’s power was achieved during the reign of Sultan Kudarat (1619-1671) who ruled over the entire southern cost of Mindanao and the Gulf of Davao. Read More

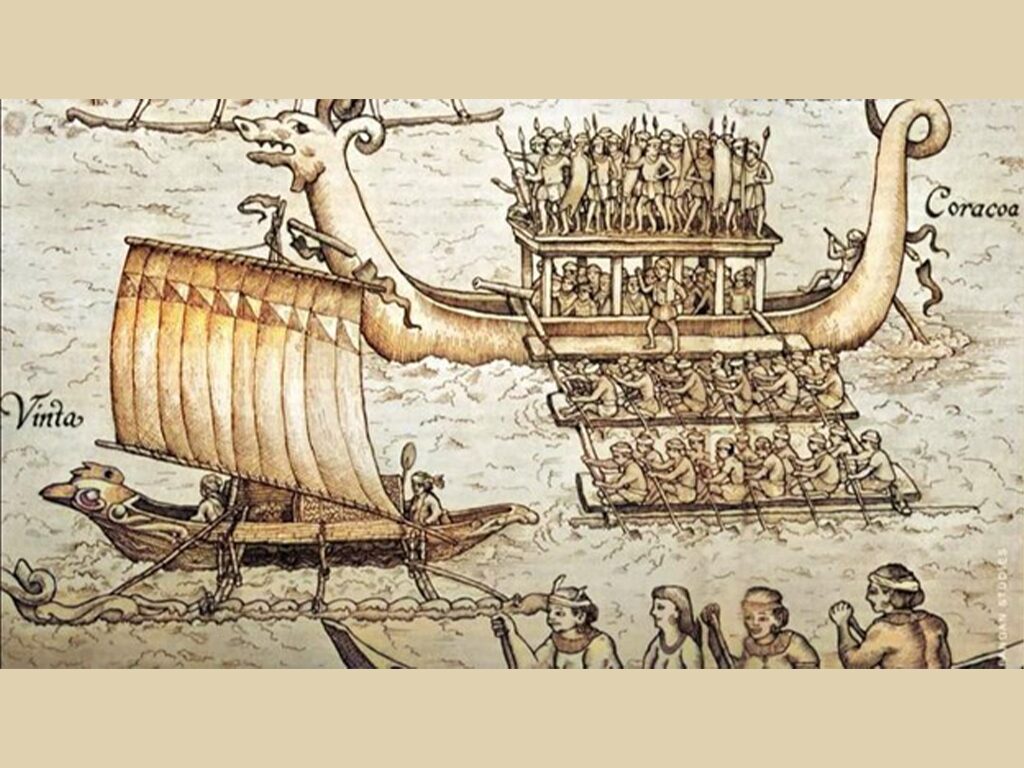

Raja Bongsu: The Beginning of an Epic Battle

1627

Raja Bongsu: The Beginning of an Epic Battle

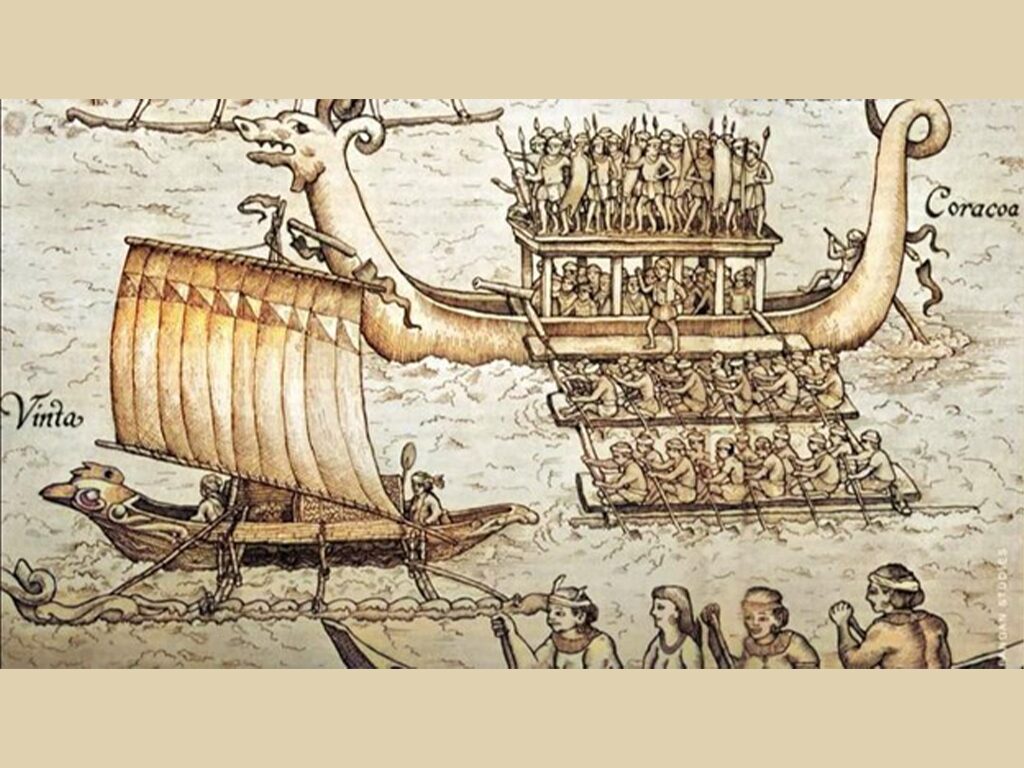

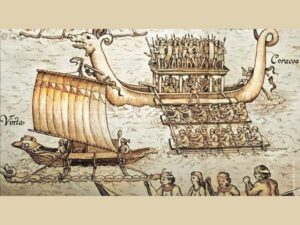

As retribution for the Spaniards’ maltreatment and robbery of Datu Ache in 1624, Raja Bongsu, in 1627, destroyed the Spanish shipyard in Camarines and took away slaves including the governor’s daughter. In the following years, the Spaniards responded by attacking Jolo and desecrating the tomb of Sultan Sharif Ali. The long and epic battle started from here.

In 1627, Raja Bongsu assembled 2,000 men and more than thirty caracoas to attack the new shipyard in Camarines. They attacked just before dawn which took the Spaniards by surprise. There were only fourteen Spanish guards, two were killed immediately, and the remaining twelve fortified themselves in a store located at the riverbank. They held out until midday together with the women, children, and the wounded. While the Tausug were busy loading an enormous amount of booty, the Spaniards escaped through a large boat at the back of the store.

Before leaving, Raja Bongsu left a letter for the governor, stating that his attack was just retribution for the treatment experienced by his ambassador, Datu Ache, in 1624. They left with 300 captives which they held as slaves, one of them a Spanish lady named Doña Lucia, who happened to be the daughter of the governor. Doña Lucia became the private secretary of Raja Bongsu later. On their way home, they took more captives from the island of Bantayan and some three hundred more from Ormoc, Leyte. When the news reached Manila, the Spanish government organized an expedition composed of 200 Spaniards and 1,500 native allies led by Don Cristobal de Lugo.

Don Cristobal attacked Jolo on one afternoon on the 22nd of April, 1628. The Tausug were surprised and unprepared since they were busy harvesting. Raja Bongsu and some followers succeeded in reaching the hillfront. The town fell to the Spaniards with little resistance. The Spaniards have taken the most luxurious booty that they ever had. Everything of value that could be carried away was taken, and the rest, including the town itself, was burned. Great quantities of food and warlike stores were destroyed, and most of all, the entire Tausug fleet was set on fire.

But the devastation in Jolo did not stop there, for Governor Don Nino de Tabora gave a mission to Don Cristobal to burn the tomb of Sultan Sharif Ali. Muslims from the whole region

pilgrimage to the tomb of Sultan Sharif Ali, one of the early Muslim missionaries who came to Sulu. Don Cristobal found the tomb without difficulty and burned it to the foundations. The troops also gained a booty worth 30,000 pesos without having suffered a single fatality. They offered the sultan 600 pesos ransom for Doña Lucia which the sultan refused. He instead demanded the return of some captured artillery.

The following year, in 1629, Datu Ache attacked Leyte. The Spaniards again responded by attacking Jolo in 1630. The expedition, however, failed as the Tausug were well-prepared. The

following year, the Tausug attacked Leyte again and took many captives for the slave market in Makassar.

Raja Bongsu’s daughter from his wife in Basilan was married to Sultan Kudarat of Maguindanao. In 1634, the combined forces of Maguindanao and Sulu attacked Dapitan, Bohol, and Leyte.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar A. 1999. Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Nicholl, Robert. 1991. Raja Bongsu of Sulu – A Brunei Hero in His Times. Council of the Malaysian Branch of Royal Asiatic Society.

Read More

Sultan Kudarat and the Battle of Ramitan

1637

Sultan Kudarat and the Battle of Ramitan

In an attempt to establish a solid foothold in Mindanao, Governor-General Sebastian Hurtado de Corcuera launched a military campaign against Sultan Kudarat in Ramitan from March 13-24, 1637. More Information: Prompted by the presence of the Dutch in Southeast Asia and the seasonal raids conducted by the Maguindanaons in the Visayas, King Philip IV of Spain decreed the pacification of Mindanao on February 17, 1636. While in he was in Zamboanga, Governor General Sebastian Hurtado de Corcuera identified the target for his attack as Ramitan, the site of the new capital of Sultan Kudarat near the Iranun... Read More

The Epic Battle: Four-Month Siege of Jolo

1638

The Epic Battle: Four-Month Siege of Jolo

After defeating Sultan Qudarat of Maguindanao in 1637, Don Sebastian Hurtado de Corquera pursued his plan to bring down Jolo and defeat Raja Bongsu and Datu Ache. An epic battle took place that lasted four months with numerous attacks and negotiations. The outbreak of an epidemic contributed to the success of the Spaniards.

After the defeat of Sultan Qudarat, Raja Bongsu and Datu Ache knew that Don Sebastian would attack them next. They started preparing for their defense. They sold in Macassar he gold and silver looted from the mission churches over the last ten years to buy arms and munitions and to hire mercenaries. Apart from the four great guns captured from the Camarines shipyard, the Tausug also acquired seven large and ten smaller bronze cannons, seven cast irons, twenty-one spare breech chambers, and uncountable arquebuses. Aside from the steep escarpment that added to their advantage, Datu Ache also installed torches of tow around the ramparts which could be lit and would last several months. He also excavated underground chambers where the women and children could take shelter during bombardments. It was the most formidable cotta ever built against the Spaniards. The Yakans, Macassars, and Malay warriors came to help the Tausug.

On January 4, 1638, Don Sebastian finally commenced his mission and landed in Jolo with 600 Spaniards, 1,000 Filipinos, and a large supply of stores and munitions in 80 vessels. Their initial attempts to infiltrate were unsuccessful. They could not cover their assault with artillery because none of their guns had the high elevation to reach the fort. Don Sebastian decided to mine the hillside and blow it to compromise the fortification above. While the mining was ongoing, Don Sebastian also surrounded the fort with a ring fence 6 miles long, with a trench set with sharp spikes, and watch towers at frequent intervals. There were also six barracks containing troops reserved for any attempt to break out in force.

On March 24, Don Sebastian detonated the mines which caused part of the defenses to collapse. The Tausug were taken completely by surprise, but the Spaniards had withdrawn back to avoid the blast and falling debris, which allowed the Tausug to thrust back. Fifty Tausug had been instantly killed and Datu Ache had been thrown and buried in debris. Fortunately, he managed to thrust out a hand, and his men recognized him and immediately dug him out. Although he was seriously injured, he was very much alive.

On March 28, Don Sebastian detonated another mine. When they reached the breach, the Tausug were waiting for them. This disappointment was compensated when Don Pedro Almonte succeeded in gun emplacement on higher grounds, allowing him to play upon the fort. Don Pedro’s one gun could fire balls weighing 80 lbs. (36.8 kilos) and four would fire balls weighing 45 lbs. (20.3 kilos). During his bombardment, he fired into the fort 80 of the first sort and 200 of the second. Women and children swarmed into the Datu’s underground shelters.

On April 5, two Yakans appeared under a flag of truce and requested permission to surrender their arms and return home. The reason behind this is the dysentery and smallpox raging within the confined space making the datu’s underground shelter a death trap. The following day, Tuambaloka, the Raja’s wife, sent a letter to Jesuit Fr. Pedro Gutierrez and asked for an interview with Don Sebastian. However, he responded that he would only negotiate with Raja Bongsu and there were three conditions before any negotiations could commence:

- The four great guns captured at the Camarines shipyard in 1627 must be returned;

- All Christian slaves held within the fort must be released;

- Church ornaments and plates, which had been looted in recent years, must be returned.,

For the next few days, Raja Bongsu and Datu Ache were in dispute. With the rampant death within the fort caused by dysentery and smallpox, Raja Bongsu and Tuambaloka were inclined to surrender to the Spaniards for the sake of their people. However, Datu Aceh was adamant about the idea of surrendering to the Spaniards. In the end, the raja’s decision prevailed.

On April 10, Raja Bongsu surrendered the guns, released all his Christian slaves, and tried to persuade the other datus to do the same. The following day, he met with Don Sebastian. In this meeting, Don Sebastian demanded that the Tausug must descend and the fort be surrendered to his soldiers. The raja agreed but requested for an extension since he still needed to convince the other datus.

On April 13, around ninety Yakans descended while the remaining 50 to 60 did not come down because they were sick. This was followed by the Macassarese who descended with a written passport from Don Sebastian. In the fort, the datus were still deeply divided on the issue of surrendering. Don Sebastian grew impatient and threatened to renew the bombardment. Tuambaloka met again with Don Sebastian and asked him to give them another three days, and together with the young Sultan Bongsu, their people would descend, to which Don Sebastian agreed.

On the morning of April 17, Raja Bongsu and Tuambaloka proceeded to lead the descent through the west gate of the fort while Don Pedro de Francia and his men entered the east gate. As the Tausug descended, the Spaniards saw only 400 fighting men, while the other 1,500 were composed of old men, women, children, and the sick.

Once they reached the vicinity of the Spanish camp, Don Pedro de Francia commanded them to surrender their arms, but the raja stated that they would only submit their arms to Don Sebastián. While they were waiting for Don Sebastian, a blinding sweltering rainstorm poured, shrouding everything. As the Spaniards ran for cover, the Tausug dropped all and disappeared into the downpour. Thus, those who had come down from the fort escaped into the countryside and to safety. Raja Bongsu and Tuambaloka remained in hiding with the Tausug, while Datu Ache slipped away and made his way to Tawi-Tawi.

On the evening of the surrender, Tuambaloka sent a letter to Don Sebastian through her nephew, Tankun. She expressed her regret stating that neither she nor her husband could avail of his hospitality for the present, as they should stay with their people. She expressed her hope that in due course they would accept his invitation. As she had left her strongbox at his quarters, the don felt sure that she would.

When the Spaniards had occupied the hill fort, they discovered enormous treasure, which the Tausug had buried within its walls. They also found a great accumulation of documents written in Arabic scripts which they all burned. There might have been two copies of the Holy Qur’an in the collection, but the others would have been commercial or administrative documents.

The Spanish triumph over Jolo was due to the intervention of unforeseen factors, the impact of smallpox and dysentery in the garrison. However, later writers tended to understate the epidemic, or even omitted it altogether, attributing the victory wholly to the bravery of the Spanish arms.

But while Jolo was defeated, Tausug in the hinterland remained to oppose the Spaniards. In July 1639, the governor, Don Luis de Guzman, led a formidable force against them. He was wounded in the fierce battle and he eventually died.

Several attempts by Raja Bongsu to regain Jolo failed. His impaired health during his twelve months as a fugitive compelled him to negotiate peace. On April 14, 1646, a treaty was signed between. A representative of Sultan Quradat, his son-in-law, was present during the signing. Datu Ache who never wanted to make peace with the Spaniards returned to Brunei.

Source:

Nicholl, Robert. 1991. Raja Bongsu of Sulu – A Brunei Hero in His Times. Council of the Malaysian Branch of Royal Asiatic Society.

Read More

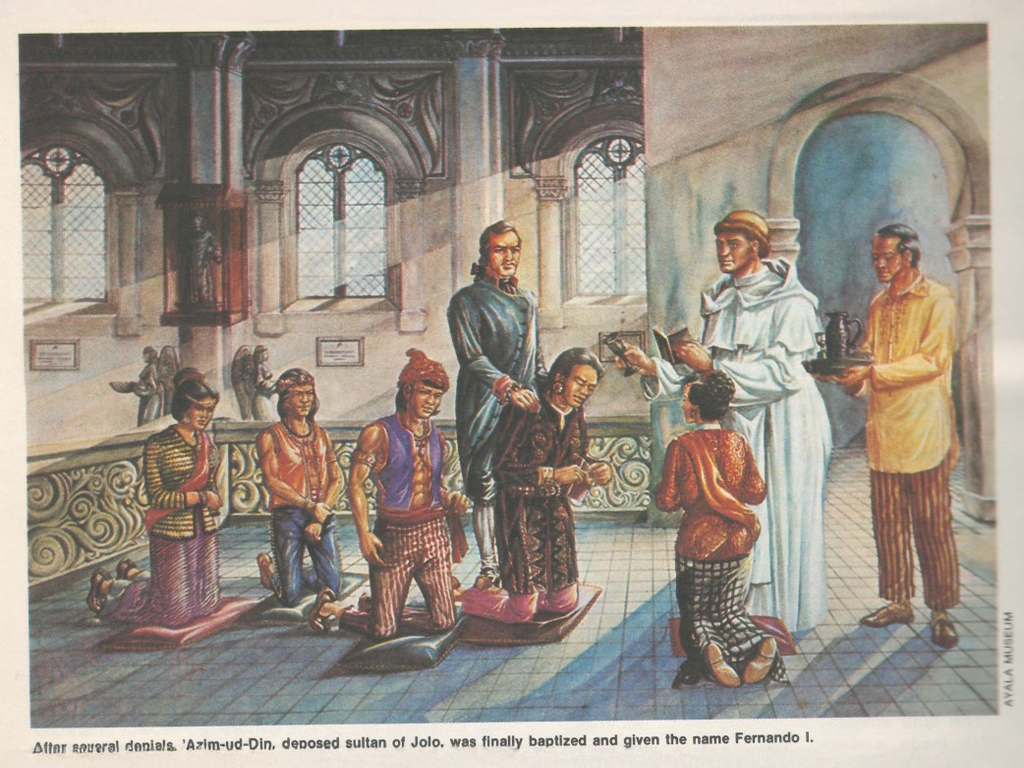

The Intriguing Story of Sulu Sultan ‘Azim ud-Din

1735-1775

The Intriguing Story of Sulu Sultan ‘Azim ud-Din

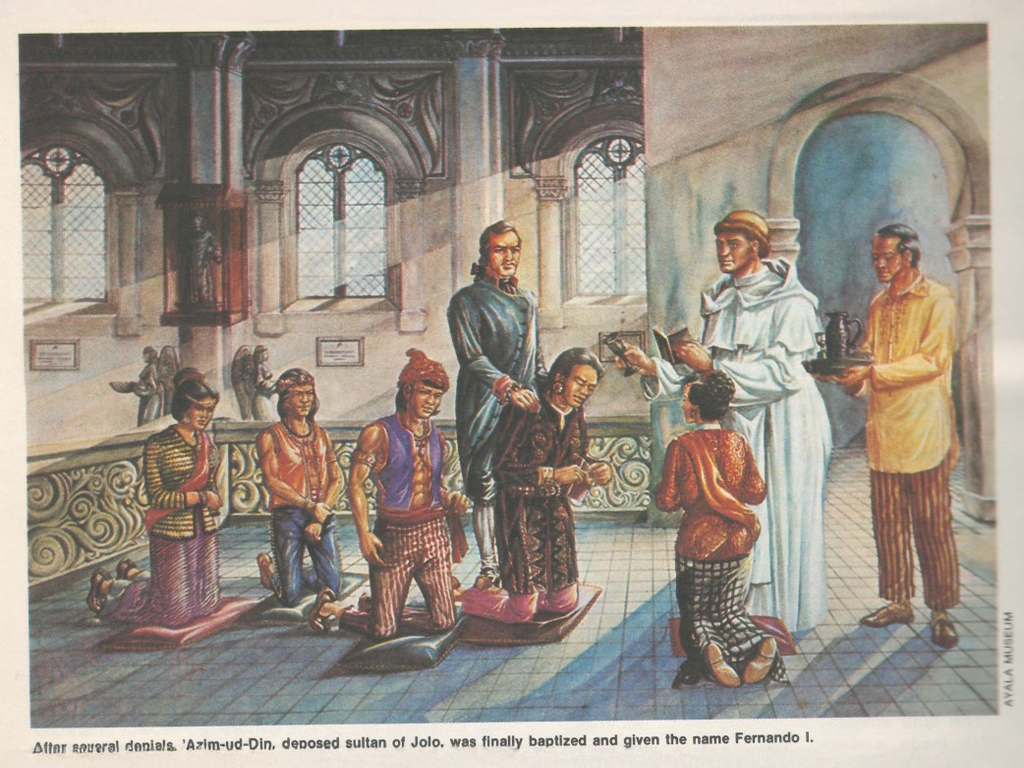

Sulu Sultan ‘Azim ud-Din was a sultan learned in Islam but converted to Catholicism in Manila after being deposed by his younger brother. His conversion was, however, questionable as he reverted to Islam when the British brought him home to Sulu and restored him as sultan by his people.

Sultan Azim ud-Din became sultan of Sulu in 1735, succeeding his father, Badar ud-Din, who spent his last years in Tawi-Tawi. As sultan, Azim ud-Din ratified the Treaty of 1737 with Spain, which acknowledged Sulu as an independent sovereign power and established peaceful relations between the two entities. However, the treaty also obligated Sulu to support Spain in conflicts, as long as they did not involve European powers. This treaty laid the groundwork for Azim ud-Din’s subsequent reliance on Spanish support to maintain his rule and suppress internal rebellions, particularly from his relative Nasar ud-Din, who challenged his authority with the backing of influential leaders including datus and the Iranuns.

Throughout his reign, Sultan Azim ud-Din faced significant internal and external challenges. In 1746, he sought to pacify the rebellious Tirun territories, notorious for their slave-hunting raids, by invoking the Treaty of 1737 to secure Spanish military aid. The Spanish responded by sending a fleet to assist him, successfully subduing the region. However, this alliance with the Spaniards alienated many of his subjects, who began to view the sultan as overly dependent on foreign powers and sympathetic to Christian missionaries, the traditional enemies of the Sulu people. Despite these tensions, Azim ud-Din made efforts to strengthen the Islamic faith within his realm by codifying Sulu laws, introducing a coinage system, and promoting Arabic as the official language.

The complications in Sultan Azim ud-Din’s reign deepened when the Spanish king, influenced by Jesuit missionaries, sought to introduce Catholicism into Sulu and Mindanao. The Spanish king sent a letter requesting that they be allowed to preach Christianity and even built a chapel in Sulu, which Azim ud-Din received with apparent sympathy. However, this further eroded his support among the Sulus, including the panditas and ulama, leading to an increasing opposition. In 1748, after an assassination attempt orchestrated by his brother, Batu Bantilan, Azim ud-Din was forced to flee to Basilan. His brother then declared himself sultan under the title Mu’izz ud-Din. Azim ud-Din later sought refuge in Manila, where he requested to convert to Catholicism, a decision that cast further doubt on his loyalty among his people.

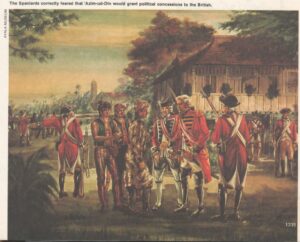

Azim ud-Din’s later years were marked by imprisonment, investigation, and eventual return to Jolo. Before the sultan left Manila, Governor Ovando asked him to write a letter to Maguindanao Sultan Amir ud-Din Hamza, explaining that Spanish support had restored him to the throne and was urging Hamza to avoid aiding Spain’s enemies and to accept Christian missionaries. Azim ud-Din complied but sent a personal letter in his dialect expressing that his earlier statements were made under duress. These letters were intercepted and used as evidence of his treason. Following the arrival in Zamboanga of many Tausug and Yakan to pay him their respects, which was seen as a threat, the governor held an emergency war council and arrested 217 Sulus, including Azim ud-Din and several prominent figures.

Because of this, he was held prisoner in Fort Santiago, and after a thorough investigation to determine the sincerity of his conversion to Catholicism, the sultan was declared a Christian by the theologians of Santo Tomas. Archbishop Rojo planned to send him and his son back to Sulu where his brother, the reigning sultan promised to return the throne. But this was spoiled by the British invasion of Manila who also had plans for Sulu. ‘Azim ud-Din offered help to Spain during the British invasion, but he was wounded. His permission to return to Sulu was denied. He contacted the British and told them his situation. The British found him in Pasig, and escorted him to Manila where he was treated and given a monthly allowance. He then entered into negotiations with the British government and gave them political concessions. The Spaniards tried to talk to him but failed. On May 17, 1764, the British escorted him to Sulu where he was well received. His nephew who succeeded his brother returned the throne to him as if nothing happened in Manila. He resumed his Islamic practices and was honored with the title Amir ul-Mu’minin, a prestigious title once reserved for the caliphs of Islam. In return for the favors which the British gave him, he ceded to them that part of North Borneo lying between Cape Inarstang and the River Frimanis with the adjacent Island of Balambangan and the Island of Tulayan. Soon after that, Balambangan was occupied and garrisoned by English forces. In 1773, he retired and gave the throne to his son. Two years after, in 1775, he died.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar A. 1999. Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Press.

Majul, Cesar A. 1978. “Sulu Power” in Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation, Vol.5 p.1332-36. Lahing Pilipino Publishing, Inc.

Read More

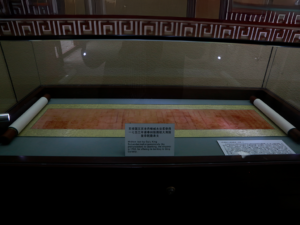

Sultan Mu‘izz ud-Din Sought Support from Chinese Emperor Against Spaniards

1753

Sultan Mu‘izz ud-Din Sought Support from Chinese Emperor Against Spaniards

While Sultan ‘Azim ud-Din was held in prison, the Spanish government attacked Sulu. His brother, Mu‘izz ud-Din, the reigning sultan, fought back and even tried to get the support of China. When peace was negotiated, the M’ranaos, Maguindanaons, and Iranuns attacked Christian settlements.

When Sultan ‘Azim ud-Din, along with his family and men, were imprisoned in Zamboanga due to his alleged treachery, the Spanish government, with the recommendation of Juan Angeles Jesuit missionary to Jolo, decided to destroy Sulu.

At the end of May 1752, a Spanish squadron with about 1,900 men led by commander Antonio Ramon de Abad attacked Jolo. The Tausug counterattack inflicted great losses on the invaders despite the three-day continuous bombardment of Jolo. The Spaniards and their native Christian allies who were interested in the booty had to retire to Zamboanga. The datus retaliated by raiding and burning towns controlled by the Spaniards. The hardest hit were Samar and Panay. Mu‘izz ud-Din, the reigning sultan of Sulu, sent a letter with a package of soil to the Chinese emperor expressing his desire for Sulu to be under China. He also sent a letter to the Ottoman sultan to seek military support.

Sultan ‘Azim ud-Din who was already brought to Manila, proposed that his sister and daughter be brought to Sulu to negotiate peace and the release of Christian captives, together with his younger brother, Sultan Mu‘izz ud-Din. Only his daughter Fatima was permitted to go to Jolo. On May 12, 1753, she arrived and was received well by his uncle. Fifty slaves were released and sent to Zamboanga.

On December 20, 1753, Fatima with Mu‘izz ud-Din’s ambassador, Muhammad Isma‘il arrived in Manila to negotiate peace. Sultan Mu’izz ud-Din, in his letter to the governor-general, requested the release of his brother, relatives, and followers, and promised that he would punish the Tiruns who were constantly conducting slave raiding. But while peace was being negotiated, the M’ranaos kept on increasing their maritime strength and accelerated their attacks on Leyte, Calamianes, and Albay. They were greatly responsible for the abandonment of many settlements in the Visayas and the dislocation of the economic life of thousands of people. They did this since most of the troops used by Spaniards against them were Visayans. The Maguindanaoans and their Iranun allies also captured the Spanish-manned Tandag fort in Eastern Mindanao. These attacks led the Spaniards to devise a more elaborate and effective naval system of defense.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar A. 1999. Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Majul, Cesar A. 1977. “Celestial Traders of Sulu” in Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation, edited by Alejandro Roces? Pls check. Vol. 3. Quezon City: Lahing Pilipino Publication.

Read More

Further Expansion of Sulu Sultanate’s Dominion

1791-1808

Further Expansion of Sulu Sultanate’s Dominion

During the rule of Sultan Shahabuddin (1791–1808), Sulu territorial expansion reached its climax through conquest and intermarriages. It included Kalimantan with Balikpapan as the seat of power, Sabah with Sandakan and Marudu as seats of power, Palawan as overseer of the Visayas and Luzon, Basilan as overseer of Mindanao, and Sulu as the overall central government. These five areas are symbolized by the five stars of the flag of Sulu (1791–1808) Read More

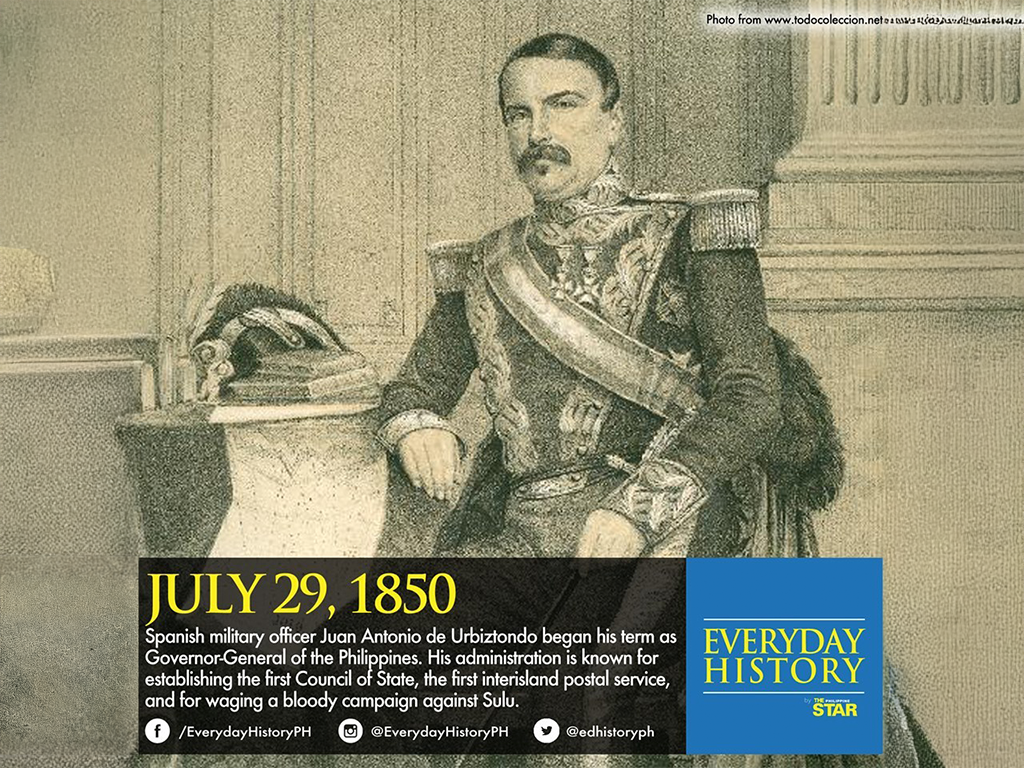

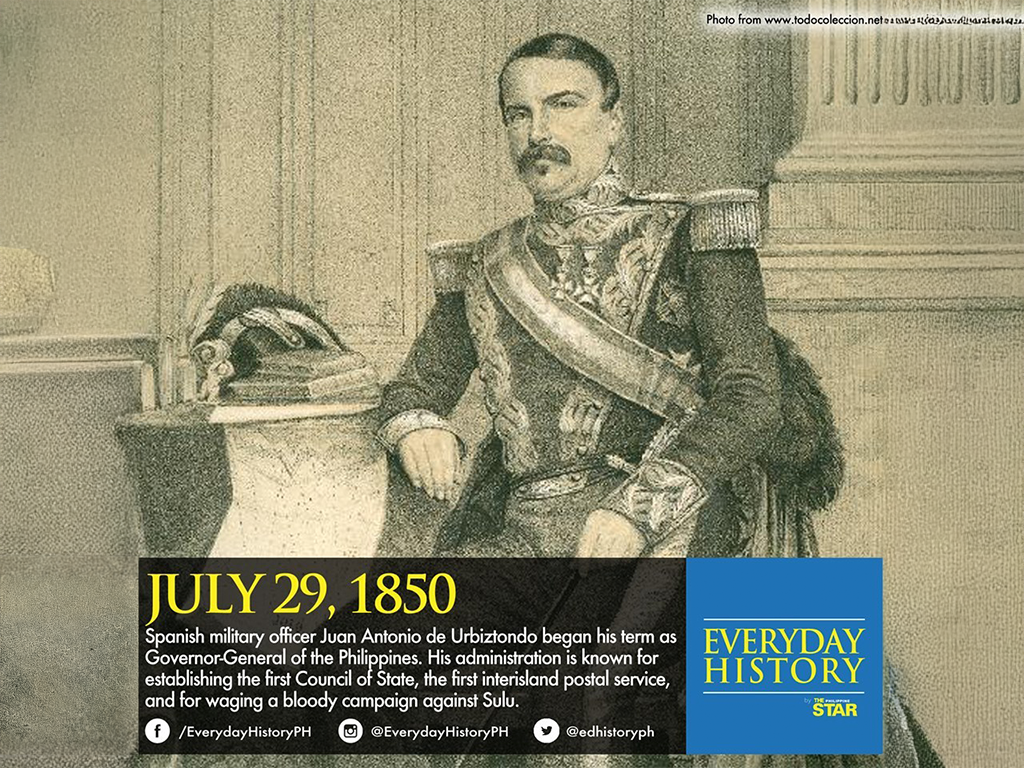

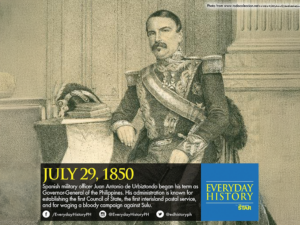

Urbiztondo and the Friendship Treaty With Sulu

1850

Urbiztondo and the Friendship Treaty With Sulu

On July 29, 1850, General Juan Antonio de Urbiztondo attacked Sulu which resulted in a Friendship Treaty of two different versions. For the Spaniards, the Sulu sultan acknowledged Spanish sovereignty. But for the Tausug, the treaty was just an acknowledgment of friendship between the two countries.

General Juan Antonio de Urbiztondo launched a military expedition from Manila to Sulu on December 11, 1850, aiming to punish the Sama Bangingi of Tungkil and their allies, while also seeking to bring the region under Spanish control. Urbiztondo was particularly concerned about the treaty signed by Sir James Brooke and the sultan of Sulu in 1849, which hindered Spain’s ambitions. The treaty’s seventh article stipulated that the sultan of Sulu would not cede any territory, recognize the sovereignty of any other nation, or pledge allegiance without the consent of Great Britain.

This prompted Urbiztondo to lead a force that included artillery, infantry, and irregular troops, initially targeting Tungkil to punish the Samals for their raids on Samar and Camiguin. However, due to bad weather, the expedition was redirected to Jolo, where they encountered significant fortifications and a well-defended population. Realizing his forces were insufficient, Urbiztondo chose not to engage in combat and withdrew.

Upon leaving Jolo on January 1, 1851, the fleet was attacked by Sulu forces, resulting in casualties and damages to the Spanish vessels. The expedition then returned to Tungkil, where they faced little resistance, burned houses, destroyed boats, and rescued captives before heading back to Zamboanga. There, Urbiztondo reinforced his troops and prepared for a second campaign. In February 1851, he returned to Jolo, where a two-day battle ensued, leading to significant casualties on both sides and the eventual destruction of the town. Despite their victory, the Spanish forces decided to evacuate Jolo, leaving it ungarrisoned.

The events in Jolo led to the negotiation of a treaty between Spain and Sultan Pulalun on April 30, 1851, written in both Spanish and Sulu. it is said that the Sulu translations were made by interpreters not well-versed in the Sulu language. The Spanish version emphasized Sulu’s acknowledgment of Spanish sovereignty, while the Sulu or Tausug version merely acknowledged a friendly union with Spain. Nevertheless, Sultan Pulalun and the key leaders agreed to accept compensation for the destruction of their properties.

National Hero, Dr. Jose Rizal, wrote a poem “El combate: Urbiztondo, terror de Jolo” (The Combat: Urbiztondo, the Terror from Jolo), a commemoration of the campaign led by Spanish Governor-General Antonio Urbiztondo in 1851 against the Sultanate of Sulu.

Sources:

Saleeby, Najeeb M. 1908. History of Sulu. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41771/41771-h/41771-h.htm

Ocampo, Ambeth. (2011). Jose Rizal in Filipino Literature and History. Entre España y Filipinas: Jose Rizal escritor Biblioteca Nacional de Espana 30 de noviembre de 2011-12 de febrero de 2012. Madrid: Agencia Española de Cooperación. https://archium.ateneo.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1042&context=history-faculty-pubs

Read More

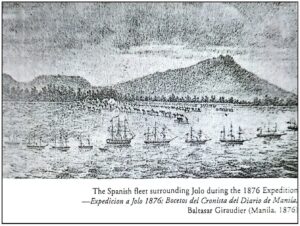

The Fall of Jolo

1876

Fall of Jolo

In a bid to break all forms of resistance and to settle once and for all the issue of sovereignty over the Muslims, Spain launched her final campaign against Sulu in 1876. A total of 9,000 troops led by Governor General Jose Malcampo occupied Sulu, but the Tausug continued their resistance in the form of parangsabil (individual jihad).

On February 05, 1876, Governor General Jose Malcampo left Manila with a large force composed of one battalion of the peninsular regiment of artillery, one company of mountain artillery, five regiments of infantry, ordnance, engineers, sanitary and prison detachments, and two companies of the guardia civil to launch his final campaign against Sulu. The expedition was reinforced in Zamboanga by 864 volunteers, 400 of whom were from Zamboanga and 464 from Kagayan de Misamis commanded by the Augustinian friar, Ramon Zueco.

A total of 9,000 troops arrived in Jolo on February 21, 1876. Tausug resistance in various parts of Sulu such as Patikul, Jolo, Parang, Siasi, and Tapul fell each day to the bombardments of Spanish artillery. On the fourth day of campaign, Maimbung, the seat of Sulu sultanate, was overrun. Sultan Jamalul A’lam moved to Bud Datu and later Likup, while the datus dispersed in all directors except for Datu Asibi and Datu Pula who remained in Patikul.

The Spaniards started to build large garrison on Jolo and other favorable spots on the edge of the swamps, the forts Alfonso XII and the Princess of Asturias were erected on the site of Daniel’s and Panglima Adak’s kuta, respectively. The Tausug regarded the establishment of these garrisons as an intrusion upon their soil and an intolerable humiliation and offense. Without waiting for a command to organize resistance, they resorted to parangsabil. They attacked and ambushed Spaniards at forests and rivers whenever they had a chance. Some even rushed to the garrison to kill as many as they could before getting killed by the Spaniards.

For more than two years, peace negotiations by the Spaniards and attempts to regain Jolo by the Tausug failed. In January 1878, Sultan Jamalul A’lam leased North Borneo for 5,000 Mexican currency to British North Borneo Company represented by Baron de Overbeck. Finally in July 1878, a peace treaty with Spain was signed that made Sulu a Spanish protectorate.

Sources:

Jubair, Salah. 1999. Bangsamoro: A Nation Under Endless Tyranny. Kuala Lumpur: IQ Martin.

Majul, César Adib. 1999. Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Saleeby, Najeeb M. History of Sulu. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing, 1908. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41771/41771-h/41771-h.htm

Read More