American Occupation

and Administration

1800

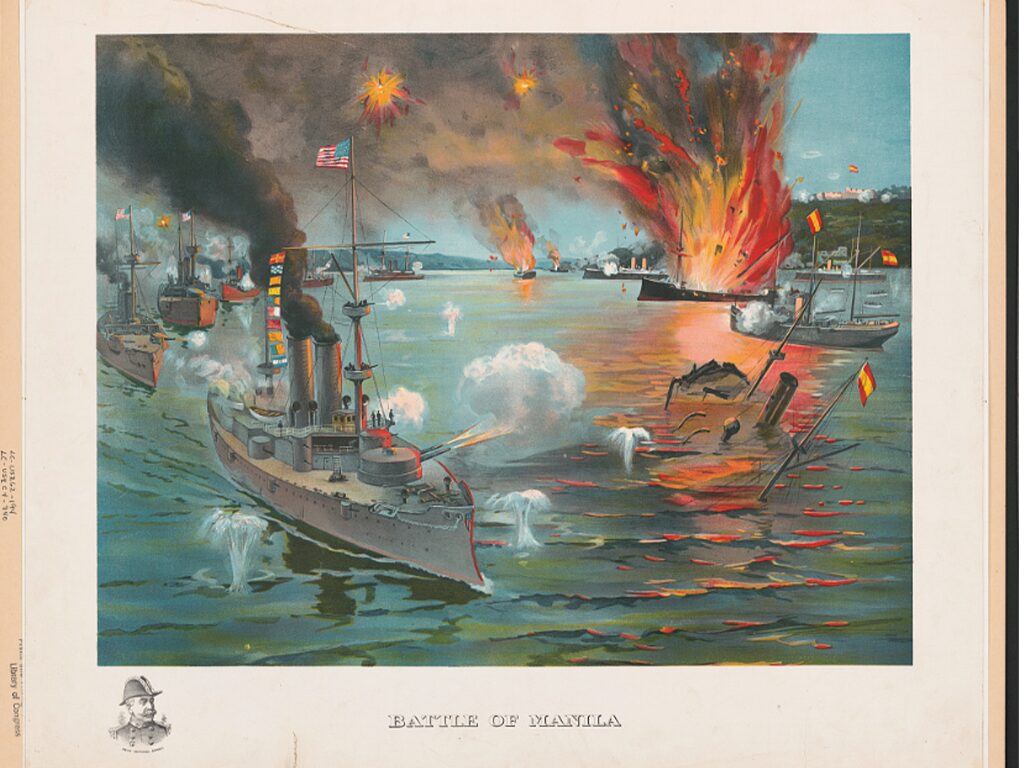

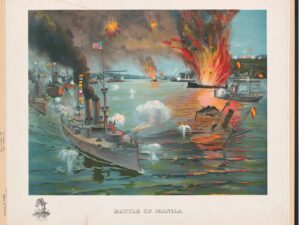

America’s Manifest Destiny and the 1898 Mock Battle of Manila Bay

The 1898 Treaty of Paris and the American Occupation of the Philippines

The 1899 Kiram-Bates Agreement

1900

Western Secular Education: America’s Tool for Colonization

1902

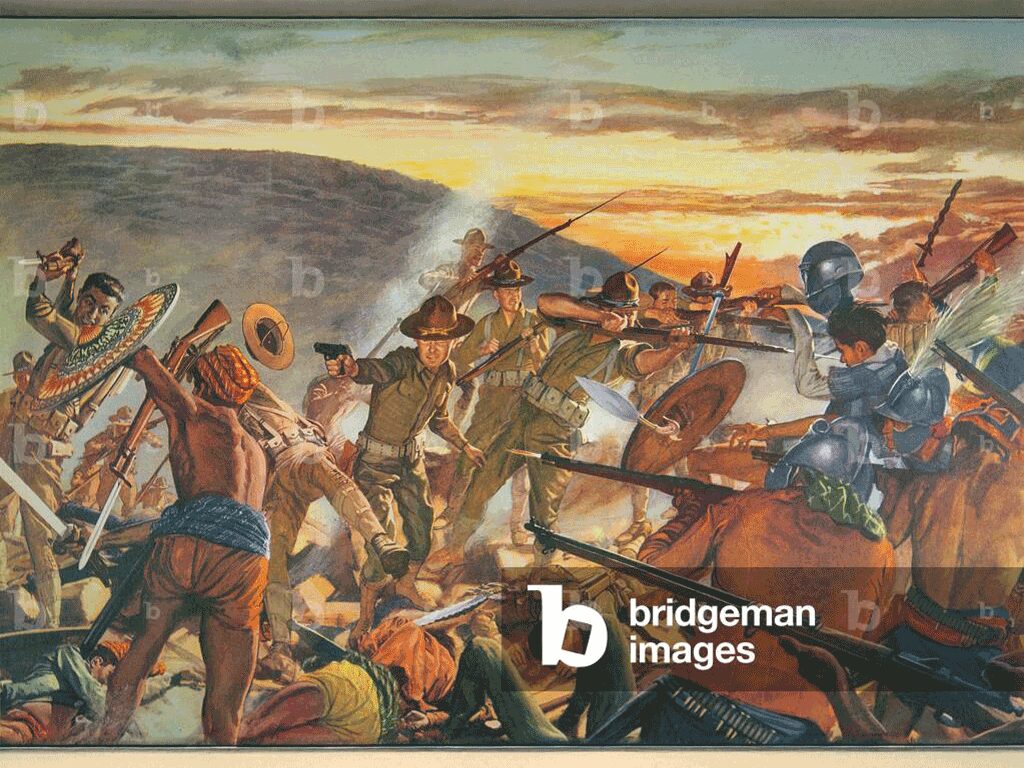

Battle of Bayang in Lanao

1903-1905

The Pursuit of Datu Ali in Cotabato

1903 - 1906

Panglima Hassan Uprising and the Battle of Bud Dahu

1910

Protests Against the Americans

1913

Battle of Bud Bagsak

1935

The Commonwealth Government

America’s Manifest Destiny and the 1898 Mock Battle of Manila Bay

America’s Manifest Destiny and the 1898 Mock Battle of Manila Bay

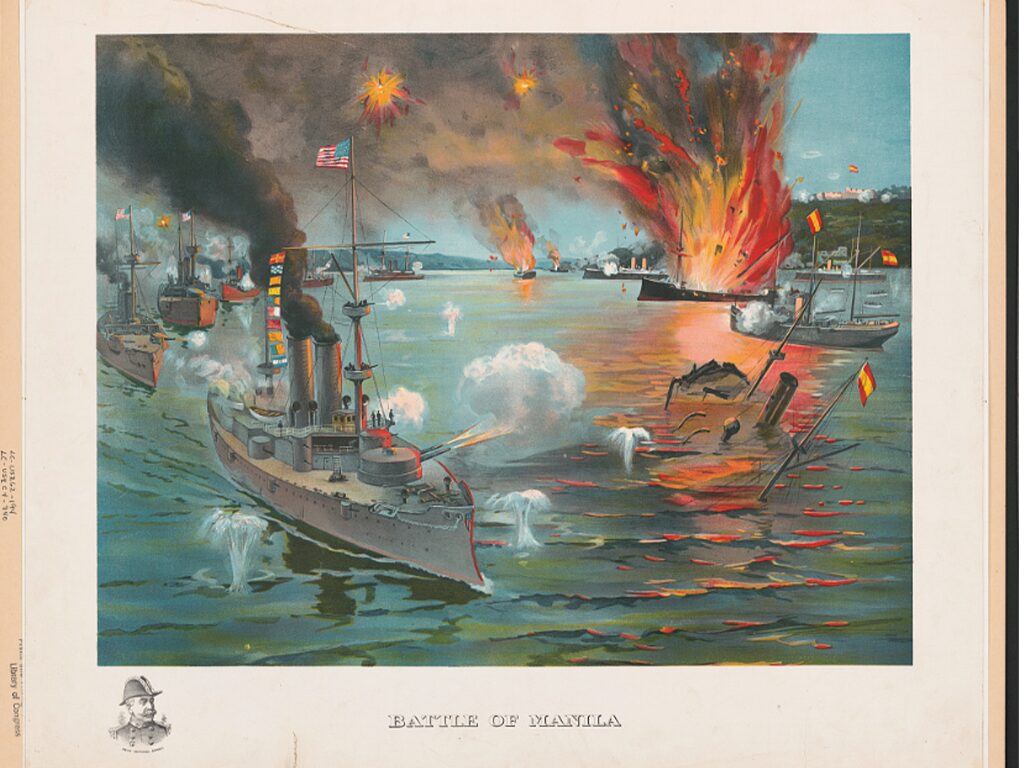

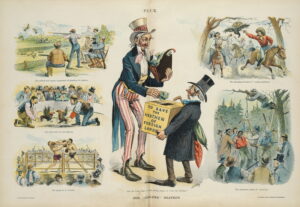

Americans’ expansionist notion of Manifest Destiny drove them further to Cuba where they fought the Spaniards. That war brought them to the shore of Manila where they eventually occupied the Philippines.

While the Spaniards had self-asserted mission of bringing salvation and civilization to the non-Catholic people outside Spain, Manifest Destiny is a notion that the United States had a mission, assigned by Divine Providence to extend the blessings of American freedom to neighboring peoples. America, being the center of civilization, had a duty to spread democracy. This notion, however, drove Americans further West into Indian territory, and as the number of Whites exceeded that of the Indians, the US government forcibly removed Indians and thought that, with the newly gained territory from the Louisiana Purchase, the Indians could be pushed out there. With the discovery of resources like gold and an expanding population, the Whites moved further and further West displacing the native inhabitants.

America’s hunger for land eventually had it eyeing Cuba, and with the destruction of the USS Maine and some colorful anti-Spanish propaganda, the Spanish-American War began and ended with the Mock Battle in Manila Bay on August 13, 1898. The Mock Battle of Manila was Spain’s graceful exit from the country with its demand satisfied. It was the result of negotiations between US Commodore George Dewey and Spanish Governor General Fermin Jaudenes to end the conflict between the United States—together with Filipino revolutionary forces—and Spain battling for control over Manila. Both parties agreed to prevent Manila from falling into the hands of the Philippine Revolutionary forces led by Emilio Aguinaldo who fought with the Americans against the Spaniards. This betrayal of Spain and America against Filipinos continued when they signed the Treaty of Paris four months later.

Sources:

Zinn, Howard. 1980. A People’s History of the United States: 1492-Present. New York Harper & Row.

Gowing, Peter G. 1983. Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos, 1899-1920. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Go, Julian. 2003. “Global Perspectives on the U.S. Colonial State in the Philippines,” The American Colonial State in the Philippines: Global Perspectives, edited by Julian Go & Anne L. Foster. Duke University.

Villar, Manny. Mock Battle: Real Battle. Manila Bulletin, August 18, 2020. https://mb.com.ph/2020/08/18/mock-battle-real-betrayal/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QynrA8l39eM

https://americanhistory.si.edu/explore/stories/mock-battle-ended-spanish-american-war

Read More

The 1898 Treaty of Paris and the American Occupation of the Philippines

The 1898 Treaty of Paris and the American Occupation of the Philippines

The 1898 Treaty of Paris formally ended the long Spanish occupation of the Philippines. Spain handed over the country to America in exchange for 20 million Mexican Dollars. Sulu and Mindanao were included without the knowledge of the Muslims and despite Spain’s failure to gain sovereignty over these areas.

https://issuu.com/phinfrance/docs/ph-fr_discovery_rediscovery-lowres/s/13118747

After the so-called Mock Battle of Manila Bay on May 01, 1898, Spain signed the Treaty of Paris with America on December 10, 1898. In exchange for 20 million Mexican Dollars, the Spanish government handed over the Philippines along with Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and Spanish West Indies, which were all under Spanish colonial holdings. While Cuba was granted independence, the Americans retained the Philippines. Sulu and Mindanao were included despite Spain’s failure to gain sovereignty over these places. This was also done without the knowledge of the Muslims.

For six months, there was a debate in the United States on what to do with the Philippines. The imperialist Republicans who urged the American government to assume full sovereignty of the Philippines as part of America’s Manifest Destiny won over the anti-imperialist Democrats who called for the recognition of Philippine Independence but under American protection. In the succeeding years, the Muslims faced another foreign colonial occupation.

Sources:

Gowing, Peter G. 1983. Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos, 1899-1920. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Read More

The 1899 Kiram-Bates Agreement

The 1899 Kiram-Bates Agreement

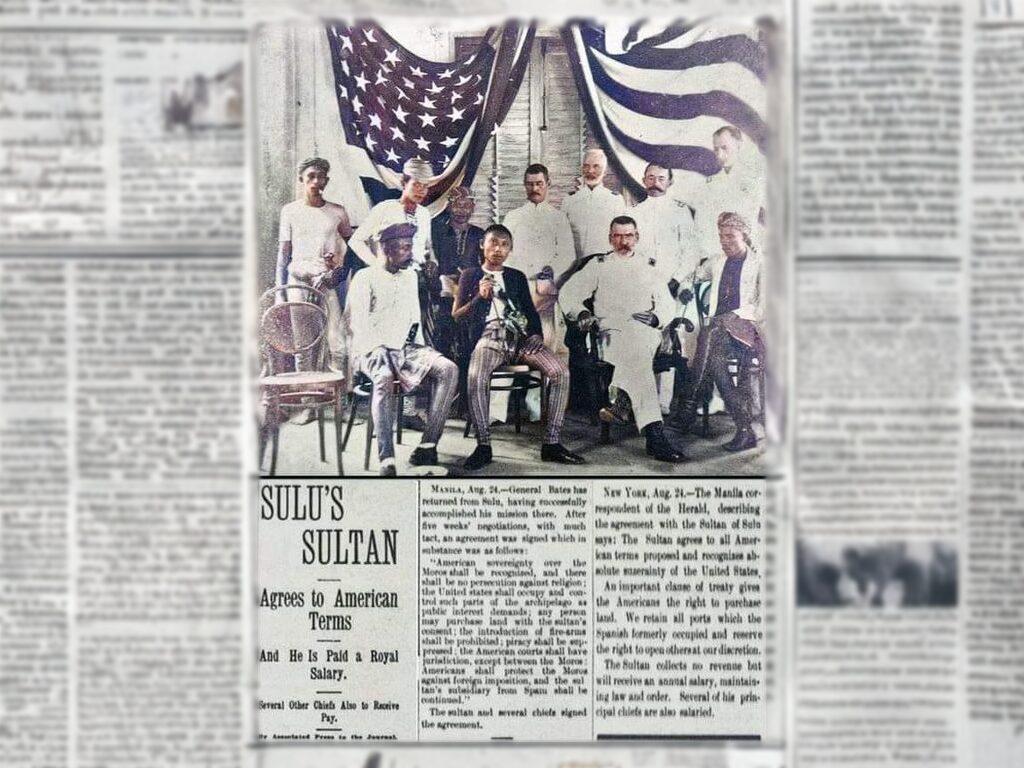

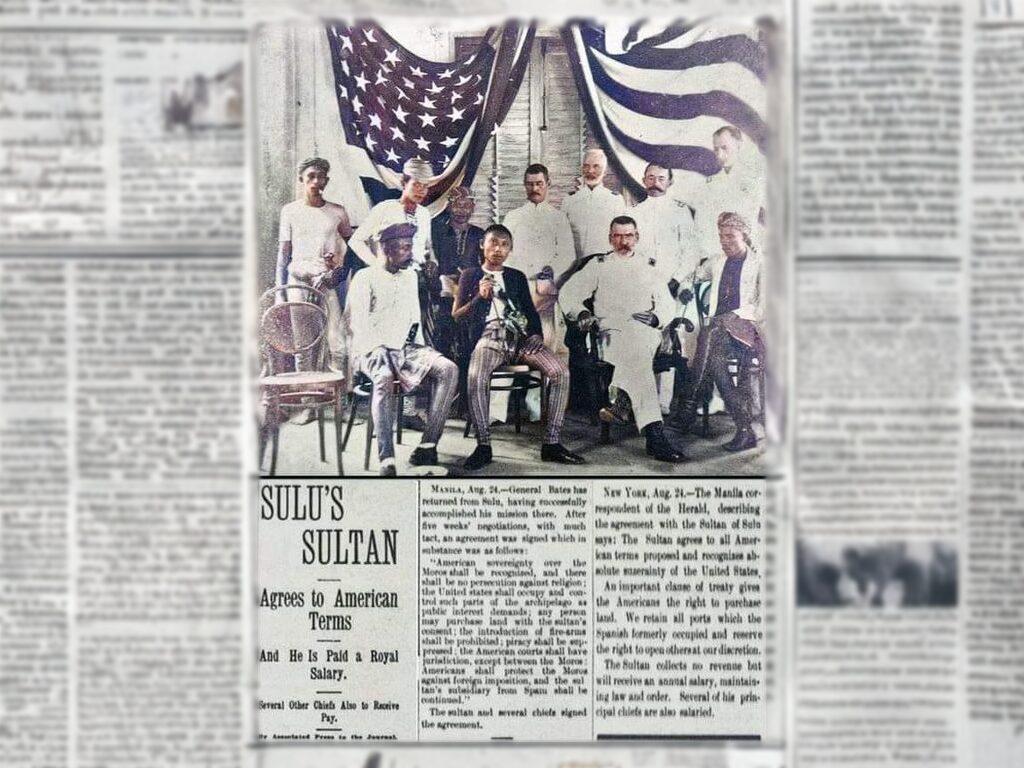

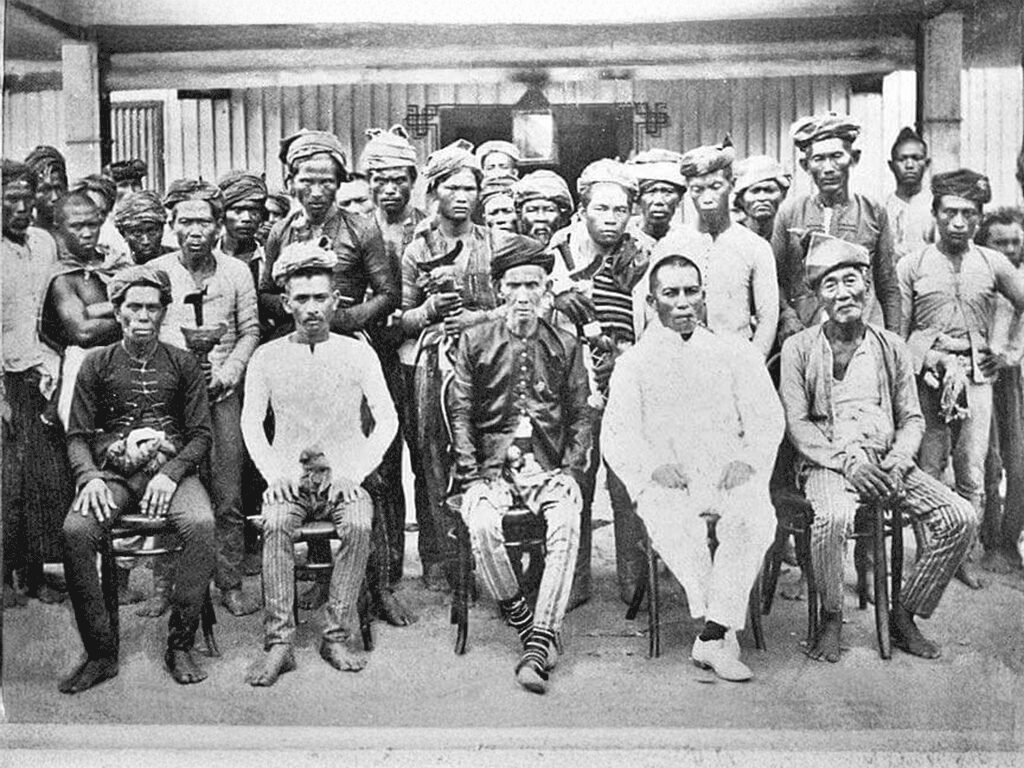

The August 1899 Kiram-Bates agreement allowed the Americans to stay in Sulu with the guarantee that they will not interfere in the religion and customs of the Tausug. But this agreement they sought with the Sulu sultan was just actually to prevent the Tausug from possible alliance with the Filipino revolutionaries in the north.

During the Spanish-American War, the insurrectos, Filipino revolutionaries headed by Emilio Aguinaldo, sided with the Americans hoping to get their independence. The insurrectos felt betrayed when the Americans decided to occupy the country after they signed the Treaty of Paris with the Spaniards. This led the insurrectos to revolt against the Americans. Emilio Aguinaldo, through a letter, solicited help from the Sultan of Sulu in their fight against the Americans pledging absolute respect of their beliefs and traditions and those of other islands. Seeing no gain in allying themselves with their traditional enemies, the sultan did not respond to the letter.

To prevent this possible military alliance, the American government sent Brigadier General John C. Bates to negotiate with the sultan. After much hesitation, the sultan agreed provided that the Americans would not interfere with the religion and customs of Sulu. Thus, on August 20, 1899, the so-called Kiram-Bates agreement was signed. But after the defeat of the insurrectos in the north, American President Theodore Roosevelt, on March 02, 1904, abrogated the agreement and other assurances of non-interference by Americans. Programs and policies that were laid down even before the abrogation of the agreement were aimed to facilitate direct control on the affairs of the Muslims.

Sources:

Gowing, Peter G. 1983. Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos, 1899-1920. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Fulton, Robert A. 2009. Moroland: The History of Uncle Sam and the Moros 1899-1920. Oregon, USA: Tumalo Creek Press.

Read More

Western Secular Education: America’s Tool for Colonization

Western Secular Education: America’s Tool for Colonization

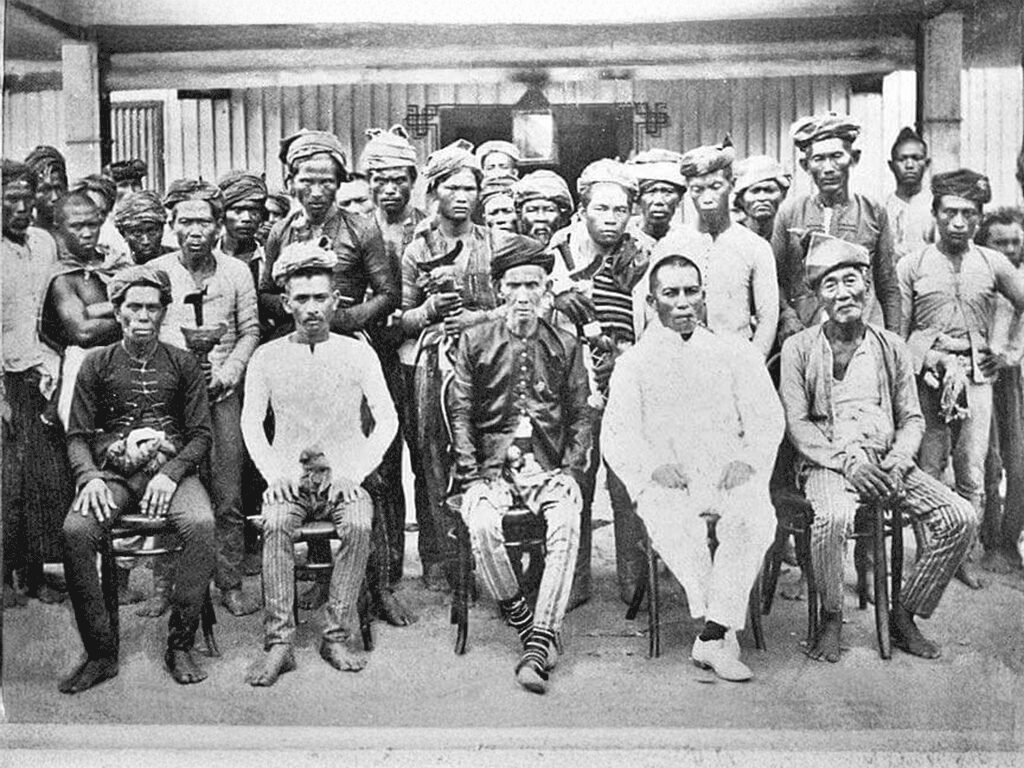

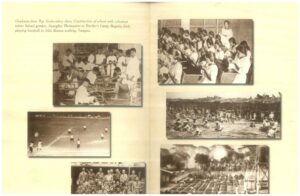

Immediately after occupying Sulu and Mindanao, the Americans implemented programs and imposed policies which undermined the way of life of the Muslims. One of these programs was western secular education aimed at separating Muslims from their Islamic faith. Other policies such as antislavery and custom regulation compelled some local chiefs to revolt.

In comparison with the Spaniards who employed conquest and Christianization, the Americans utilized the policy of attraction and pacification. But like the Spaniards, they also had similar prejudice against the Muslims. The programs and policies they formulated were extension of what they implemented for the Christian population. And while they assert the noninterference on religion, they found Islam as an obstacle to promote Christian civilization, and it was necessary for them to eradicate it. The Muslims knew how the Christianized people in the north lost their identity to American education. And so, while they welcomed some programs of attraction policy such as health, infrastructure, and commerce, they did not receive well the education program. In the beginning of its implementation, only few Muslims went to school compared to those who remained studying in Pandita schools. Many schools especially in Lanao areas were burned down by the M’ranaos.

The once independent sultanates were reduced into one province, the Moro province. Powers of the sultans and datus were minimized. The Muslims were not also comfortable when Americans abolished the policy of slavery, as if they had not enslaved hundreds of thousands of Africans in America. The opening of Mindanao and Sulu to Christian settlers resulted in the gradual loss of Muslim ancestral lands. The imposition of custom regulation and taxation brought more hardships to the Muslims. Those who defied American rule were pacified through military operations. The Muslims continued to fight.

Sources:

Gowing, Peter G. 1983. Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos, 1899-1920. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Milligan, Jeffrey Ayala. 2005. Islamic Identity, Postcoloniality, and Educational Policy: Schooling and Ethno-Religious Conflict in the Southern Philippines. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Read More

Battle of Bayang in Lanao

1902

Battle of Bayang in Lanao

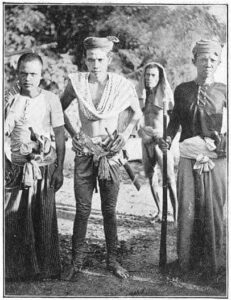

American occupation in Mindanao was immediately met with armed resistance by the M’ranao in Bayang in May 1902. The Sultan of Bayang along with his more than three men were killed defending their territory in a three-day bloody encounter. This first armed resistance against the Americans was called Padang Karbala by the Muslims. Read More

The Pursuit of Datu Ali in Cotabato

1903-1905

The Pursuit of Datu Ali in Cotabato

Datu Ali was the last and most formidable Muslim ruler to oppose American rule in Mindanao. It took almost two years with several US Army formations and Philippine Constabulary to pursue him. He was killed in 1905.

Datu Ali from Kudarangan was the son of Datu Utu and the son-in-law of Datu Piang who succeeded Datu Utu. Before the Americans, Datu Ali has fought the Spaniards in his refusal to honor Spanish flag. In 1886, he attacked the town of Lepanto near the Spanish fort of Bugcaon, killing fourteen and looting the place as the campaign ended

He refused to obey the anti-slavery law of the Americans and attempted to raise the entire Cotabato Valley to revolt against the Americans. His agents also sought to convince the M’ranaos of Lake Lanao to join him. In early March 1904, General Leonardo Wood captured Datu Ali’s main cota in Kudaranga. But Datu Ali escaped along with his men. He shifted to a guerrilla warfare against the Americans. In May 1904, his men killed two officers and 17 men when they ambushed a company of the 17th Infantry. The wounded were captured and cared for. Later they were sent back to an army post.

His men continued to raid the lower Cotabato valley, keeping the area in turmoil for nearly eight months. Months of previous military operation against him failed until a Muslim guide informed the Americans of his whereabouts. Finally on October 22, 1905, a surprised attacked on his hideout at Malala River killed him and several hundreds of his followers.

Sources:

Gowing, Peter G. 1983. Mandate in Moroland: the American Government of Muslim Filipinos, 1899-1920. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Hurley, Vic. Swish of the Kris: The Story of the Moros. E.P. Dutton and Co., Inc., 1936.

Read More

Panglima Hassan Uprising and the Battle of Bud Dahu

1903 - 1906

Panglima Hassan Uprising and the Battle of Bud Dahu

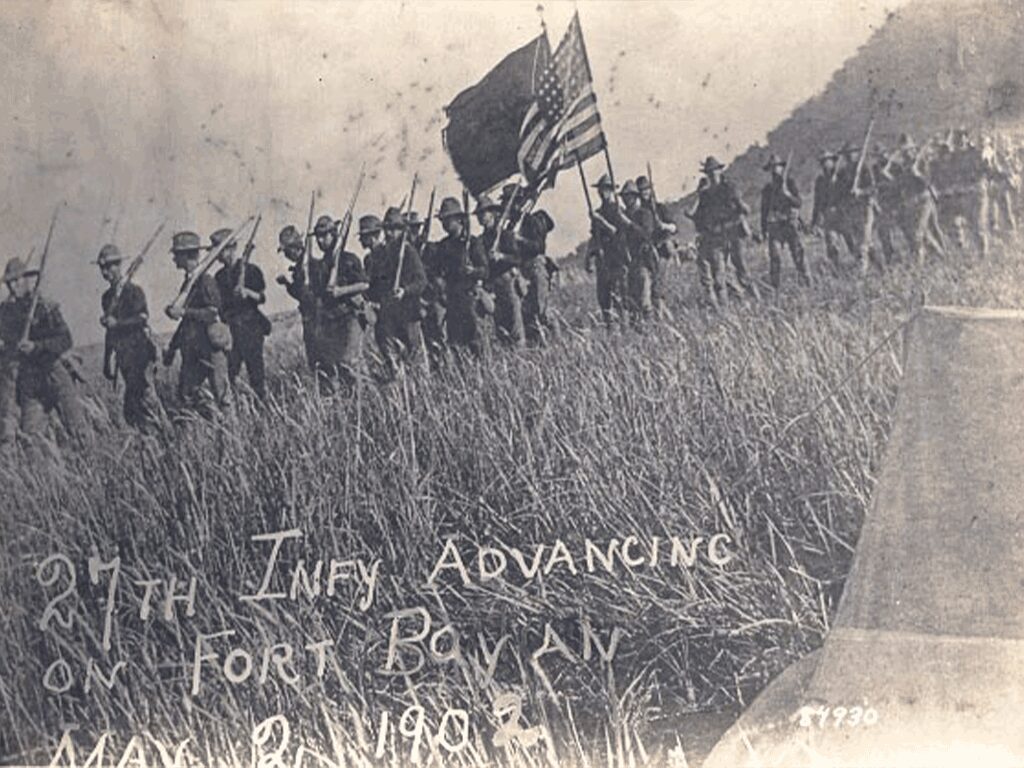

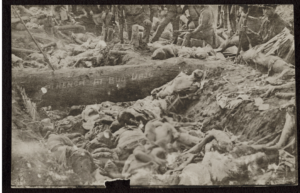

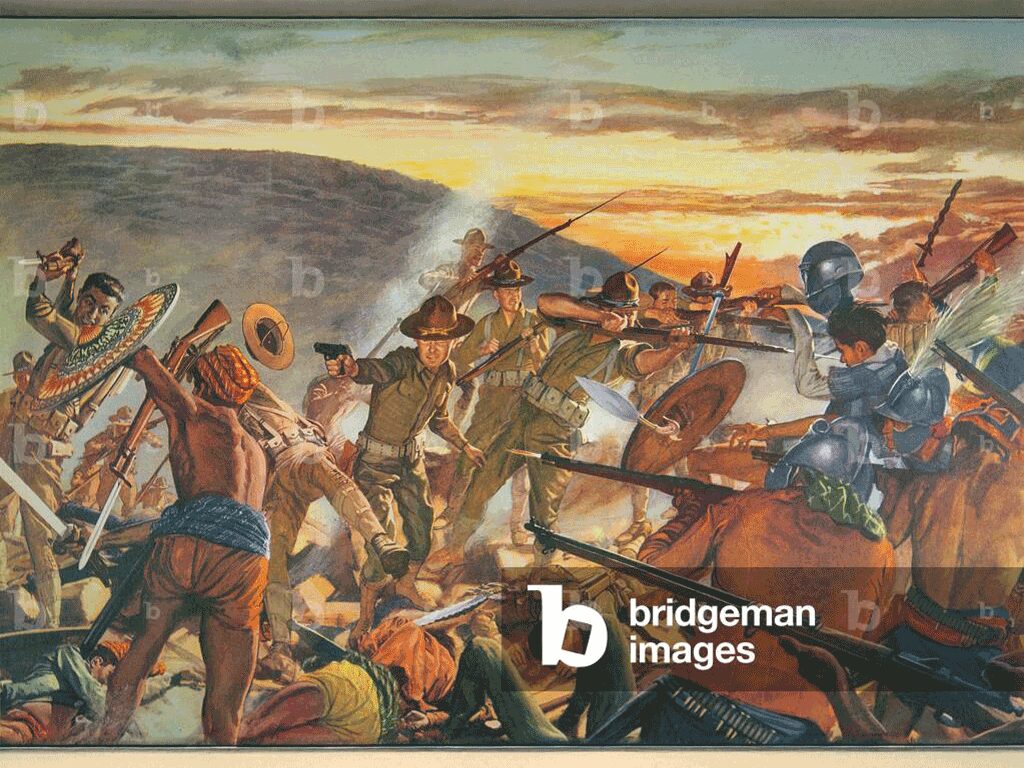

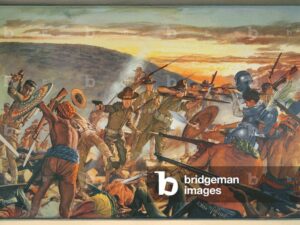

As early as 1903 when the Americans imposed the anti-slavery law, Tausug in Sulu started to revolt. The first was Panglima Hassan uprising, followed by the Battle of Bud Dahu in 1906 where almost a thousand Tausug men, women, and children died fighting against American soldiers with more advanced weapon.

Immediately after the American imposed the anti-slavery law in 1903, a powerful local chief, Panglima Hassan from Luuk led an uprising. In November 1903, General Leonardo led a military campaign against him in his cota near the Siet Lake in his hometown in Luuk where the latter lost many of his men. The following month, he surrendered but escaped when an ambush occurred while on their way with the American soldiers to fetch his wife and children. In March 1904, during a fierce battle on top of Bud (mount) Bagsak, he was finally killed with thirty-three bullets hitting his body.

Datu Laksama Usap, one of Panglima Hassan’s sympathizers, continued the resistance with his Arab preacher. In January in 1905, the same Major Scott who killed Panglima Hassan went against them. Datu Laksama was killed while the Arab preacher was captured and deported to Singapore. A few months after, another local leader named Pala declared a Jihad against American authority. In April, his men attacked the walled city of Jolo and raided nearby settlements. In early May, General Wood commanded a series of military operations near Mt. Talipao until Pala was killed. His men scattered and continued to fight occasionally until the last of them was killed in November.

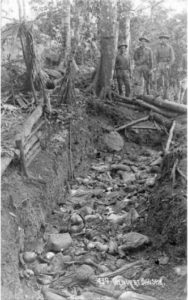

The imposition of cedula or tax in 1905 gained widespread opposition among the masses in Sulu. While the American government managed to get the cooperation of the sultan and other datus, still many of sultan’s followers and other leading datus such as Julkarnain, Calbi, and Maharaja Indinan could not accept this foreign law. They and other Tausug who objected American policies began to organize opposition on a large scale. They gathered and fortified Bud Datu. On March 5, 1906, following failed peace efforts to make them surrender or at least send down their women and children, American forces launched an assault. The Tausug, numbering around 1,000, held a strong position but were overwhelmed by American artillery and bayonet charges. The three-day battle ended in a massacre, with only six Tausug surviving out of 1,000, while 21 Americans were killed and 75 wounded. It was the strongest resistance in the Philippines ever organized against the Americans.

The Battle of Bud Dajo was widely criticized as unnecessary bloodshed, highlighting the challenges of enforcing American rule in the region. In the U.S., General Wood was tagged for the carnage. The senate also demanded a full report from the War Department.

Sources:

Gowing, Peter G. 1983. Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos, 1899-1920. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Fulton, Robert A. 2009. Moroland: The History of Uncle Sam and the Moros 1899-1920. Oregon, USA: Tumalo Creek Press.

Hurley, Vic. 1936. Swish of the Kris: The Story of the Moros. New York: E. P. Dutton and Co., Inc.

Read More

Protests Against the Americans

1910

Protests Against the Americans

America’s plan to retain Mindanao and Sulu as part of the Philippines was met with strong opposition from Muslim leaders in Sulu, Zamboanga, Maguindanao, and Lanao.The American government and the Filipino Christian politicians in Manila knew well that the economic future of the country depended on Mindanao and Sulu resources. Thus, inclusion of these two Muslims areas was deemed important in establishing a self-sustaining country. But the Muslims preferred to be independent or to remain under the United States of America than be handed over to their traditional enemies, the Filipino Christians.

.

In a mass meeting during the visit of Secretary of War Jacob M. Dickenson in Zamboanga in August 1910, Datu Mandi, Datu Sakaluran, Datu Nuño, and Ulangkaya Ujaton expressed their unwillingness to be part of the Philippines, instead desiring to have a separate independent state or to remain in the hands of the Americans.

Not long after the management of the Bureau of non-Christian Tribes was passed on to Christian Filipinos in 1920, fifty-seven prominent Tausug leaders presented a petition to the president of the United States of America during the visit of Wood-Forbes mission to Sulu in 1921. They were asking that Sulu be governed separately from the rest of the Philippines. The petition also charged Christian Filipino officials with abuse of power. This was again followed by declaration of rights and purposes in February 1924 signed by more than a hundred signatories including the Maguindanao Sultan Mangingin, Abdula Piang, Datu Benito, and the Muslim leaders in Zamboanga. A portion of the declaration states

“… In the event that the United States grants independence to the Philippine islands without provision for our retention under the American flag, it is our firm intention to resolve to declare an independent constitutional sultanate to be known to the world as Moro Nation. It is the duty of the Congress of the United States to make provision at once for the security and protection promised to us when we surrendered our arms to the United States Army. This promise just as sacred as any alleged promises you have made to the Christian Filipinos. You have left us defenseless, and it is your duty to protect us or return to us the weapons you took from us and which we freely gave you, relying on your promise.”

Meanwhile, some policy makers in America also shared the idea of separation. Two bills were introduced to the US Congress, the 1926 Bacon Bill which proposed the retention of Moro province under American rule while granting independence to Luzon and Visayas, and the Cooper Bill which also proposed the retention of Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan for eventual federation with the United States.

Later, in 1934, when the US Congress passed the Philippine Independence Act which gave a ten-year commonwealth status before the total independence, a mass marching to oppose the inclusion of Moro land into the Philippines was held in Marawi (Lanao). A written letter known as the Dansalan declaration was also sent by more than a hundred Maranao leaders to US President Roosevelt explaining the religious differences between the Muslims and the Filipinos, expressing their disagreement and the negative consequences if Moro land will be included as part of the Philippines. Instead, they wanted to remain under the Americans whom they believed were more religious tolerant and respectful of their way of life compared to the Christianized Filipinos who had been their enemies.

However, all those demands by the Muslims in a series of protests were not granted. The American government instead favored the pressure of the Filipino Christian politicians to maintain a unified country.

Sources:

Gowing, Peter G. 1983. Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos, 1899-1920. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Jubair, Salah. 1999. Bangsamoro: A Nation Under Endless Tyranny. Kuala Lumpur: IQ Martin.

Abas, Datucan M. 1971. “Muslim Secession Movement in the Philippines.” M.A. Thesis. Manila: Manuel L. Quezon University.

Read More

Battle of Bud Bagsak

1913

Battle of Bud Bagsak

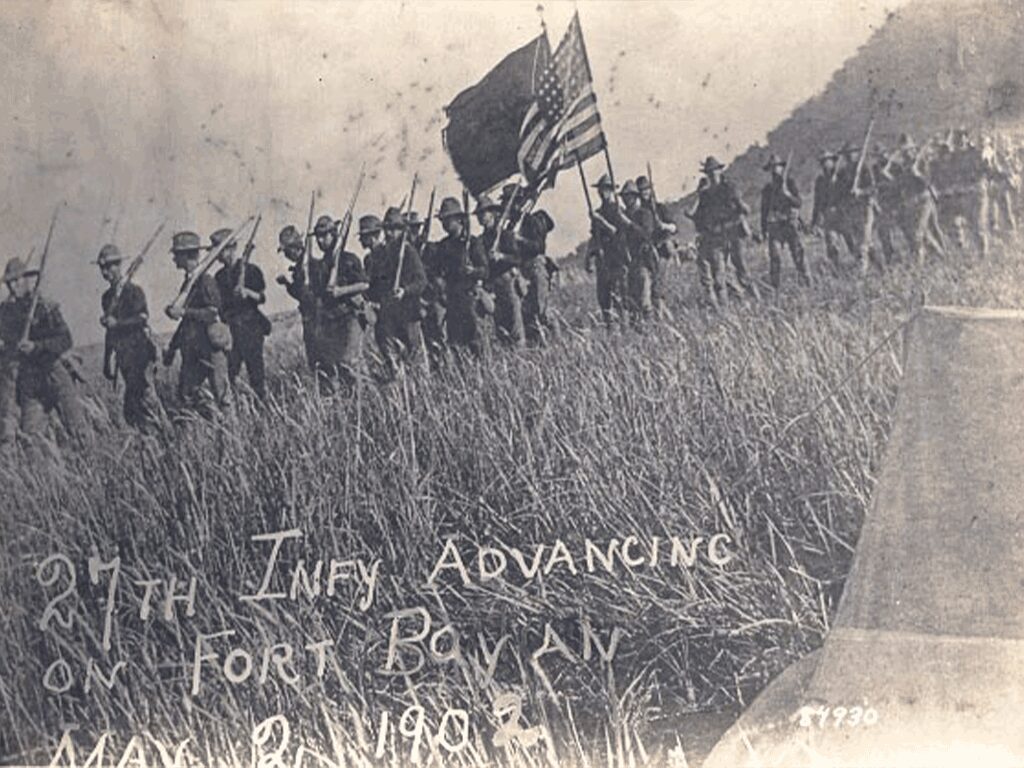

Another American policy, the disarmament, forced the Tausug in Sulu to organize another armed resistance in Bud Bagsak in 1913. The war lasted five days killing around five hundred Tausug fighters.

Peace and order conditions in Sulu and Mindanao greatly improved since General Wood’s time. However, his successor, General John H. Pershing believed that full respect of the law will not happen in Moro land unless the Muslims were disarmed. On September 08, 1911, he issued Executive Order No. 24 prohibiting the possession and acquisition of a deadly weapon in the entire Moro province. Some opposition in Lanao was suppressed by swift action of the army and constabulary. In Cotabato, a certain Datu Alameda gave the authorities trouble, but he was eventually driven into the interior.

The strongest resistance to disarmament policy was in Sulu. About 1,300 Tausug fortified again Bud Dahu. But General Pershing’s strategy of cutting them food supplies to starve them led into their gradual dispersal, except for a few who fought and were captured. But in Lati, Patikul, Tausug were still opposing the disarmament. They attacked American troops. In January 1913, a combined force of constabulary and scouts engaged their group led by Naqib Amil and his brother Datu Jami, and Datu Sahipa. Both sides had many casualties. When military reinforcements arrived, they retired to Bud Bagsak with almost the entire population of Lati. After several months of negotiations, most of the women, children, and unarmed came down the mountain. But the three local leaders and their men remained to fight. They had fortified five key positions, including the main fort of the mountain.

On June 10, 1913, American forces, led by Pershing, launched a surprise attack. The American troops were divided into two wings, each tasked with capturing the outlying forts. After intense fighting, several forts fell to the Americans, including Matunkup, where troops had to scale a sheer cliff under heavy fire. Despite fierce counterattacks of the Tausug, American forces steadily advanced, with heavy casualties on both sides. On the third day, the Americans captured the crucial fortress of Bunga, allowing them to position artillery for the final assault on Bud Bagsak. On the fourth day, after hours of intense fighting and a two-hour barrage, the American troops stormed the final defenses. Pershing personally oversaw the final assault, and by the end of the day, the Tausug were defeated. Around 500 Tausug, fighting bravely to the death, were killed. This battle marked the end of organized Muslim resistance against American forces.

Muslims “as fighting men,” says American author Vic Hurley, “they take first rank in the pages of martial history. They were responsible for the change in regulations of the United States army, providing for the substitution of a .45 caliber pistol for the .38 caliber weapon formerly carried as a sidearm. The .38 caliber bullet was incapable of stopping the Muslim in time to save the soldier who had fired the shot.

Sources:

Gowing, Peter G. 1983. Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos, 1899-1920. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Fulton, Robert A. 2009. Moroland: The History of Uncle Sam and the Moros 1899-1920. Oregon, USA: Tumalo Creek Press.

Hurley, Vic. 1936. Swish of the Kris: The Story of the Moros. New York: E. P. Dutton and Co., Inc.

Read More

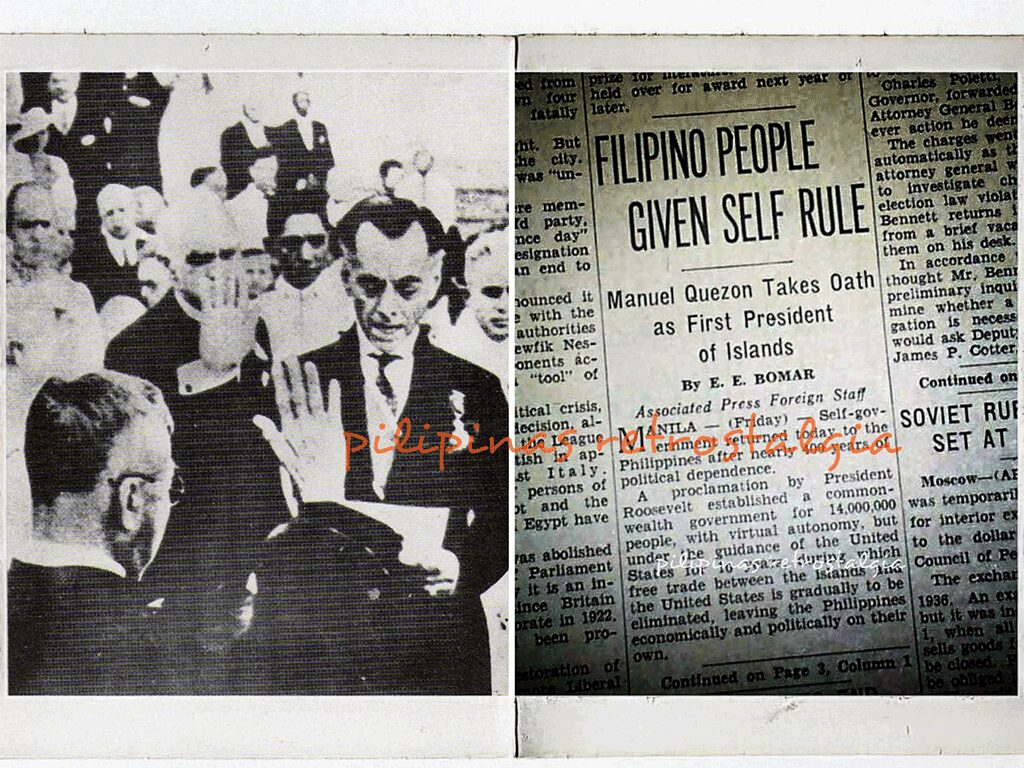

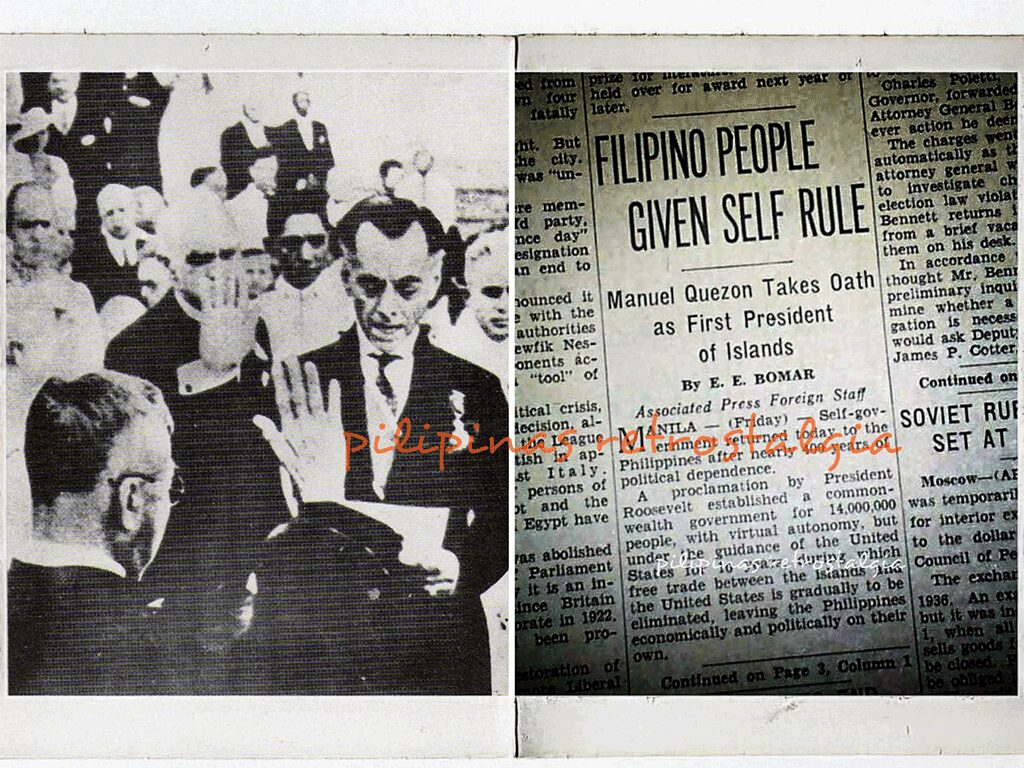

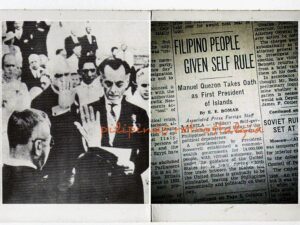

The Commonwealth Government

1935

The Commonwealth Government

During the Commonwealth Government, the sultanate was dismantled, and more Christian settlers were sent to Muslim areas in Mindanao.

The Commonwealth Government (1935-1946) headed by President Manuel L. Quezon provided transition for the Christian Filipinos to crystallize the direction of the country (Tan 1993). But the Filipino government only continued what they inherited from their colonial masters. The Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes was abolished and was replaced by the Office of the Commissioner for Mindanao and Sulu. This time, Americans’ policy of persuasion and attraction on Muslim affairs was transformed into political, economic, and social integration into the Filipino identity. Commonwealth policies were aimed at the economic development of Mindanao and Sulu. But they were not, however, guided by the history and cultural heritage of the Muslims. President Quezon dismantled the sultanate and the power of the sultan and the datus were no longer recognized. In number three of his September 20, 1938 memorandum to the Secretary of the Interior, he wrote that this nonrecognition of the sultan’s and datus’ power was to protect the common people from the control and exploitation of their leaders, to recognize their rights and equality with the titled datus and in order that they be heard and consulted.

Commonwealth policies became even more problematic when the government, through its Homestead Law, encouraged thousands of Christian settlers from Luzon and the Visayas to migrate to Mindanao in order to solve the country’s economic crisis and the security problem especially in the south. This transmigration was a program started by Americans to facilitate interactions between the Filipinos and Moros as part of their desire to promote national unity. During the commonwealth period, the number of Christian settlers increased dramatically. Not only that, President Quezon also pushed to admit several thousands of Jews who were fleeing persecutions. Two hundred and fifty of them were sent to Mindanao to work in then-prospering abaca plantations.

Many of those Christian settlers were poor and ignorant. At first, the Muslims, especially their leaders, helped the Christian settlers, shared their work animals, crude tools, and equipment. Some were even adopted by the datus. But when the government facilitated the land ownership titles which allowed Christian settlers to acquire lands in Mindanao that were traditionally owned by the Muslims, the Muslims slowly lost their ancestral lands.

Sources:

Gowing, Peter G. 1979. Muslim Filipino: Heritage and Horizon. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Gross, Max L. 2007. A Muslim Archipelago: Islam and Politics in Southeast Asia. Washington, DC: NDIC Press.

Majul, Cesar Adib. 1985. The Contemporary Muslim Movement in the Philippines. Berkeley, CA: Mizan Press.

Luga, Alan R. 2002. “Muslim Insurgency in Mindanao, Philippines.” A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of U.S. Command Army and General Staff College. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

Tan, Samuel K. 1993 Internationalization of the Bangsamoro Struggle. Quezon City: Center for Integrative and Development Studies, University of the Philippines and University of the Philippines Press.

Read More