Bangsamoro

Historical Timeline

BC

6810

Early Civilization 6810 - 3190 B.C.

AD

800AD - 1365

Indian Link and Influences

800 - 1365

What the Muslims Learned from Their Long Interaction with the Chinese

Further Spread to Luzon and Visayas

982

1270-1275

Arrival and Spread of Islam in the Sulu Archipelago 1270-1275

1300

AD 1370

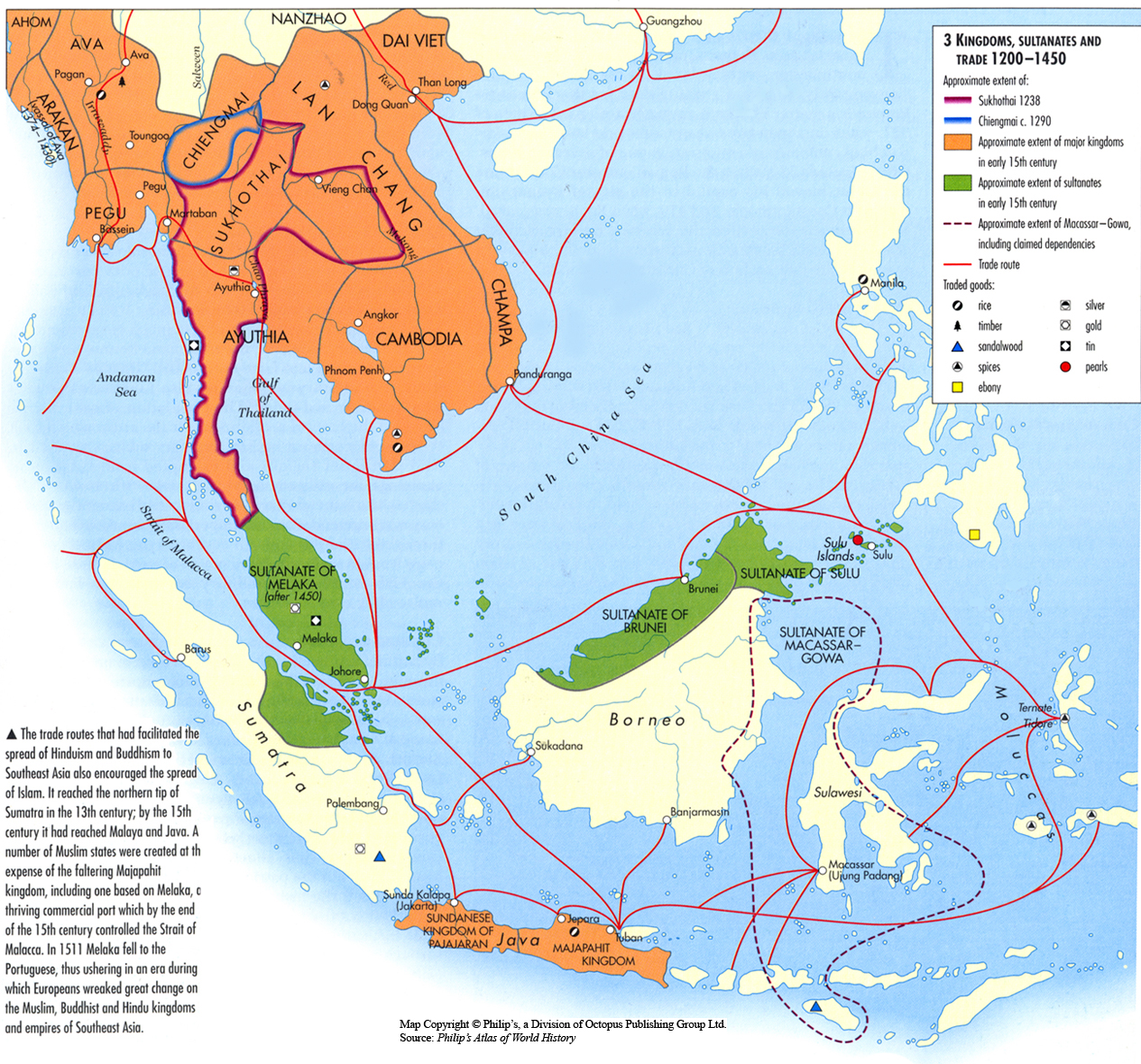

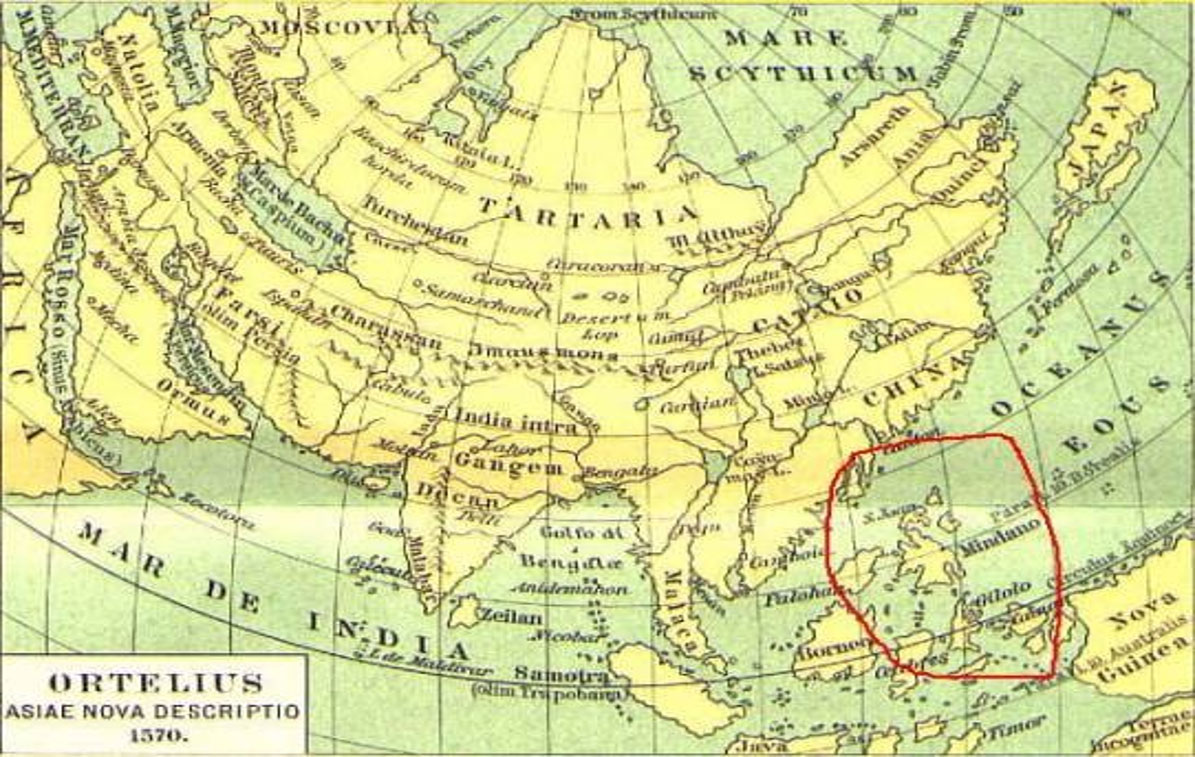

Map of Mindanao in Asia

1300

Islam’s Further Spread to Maguindanao and Lanao Areas

1400

1405

Islam Moves North

1450

Legacy of Islam in Luzon and the Visayas

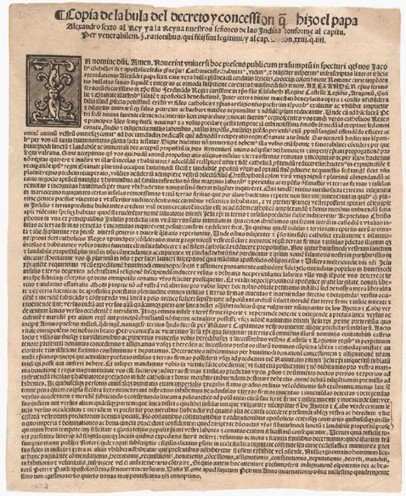

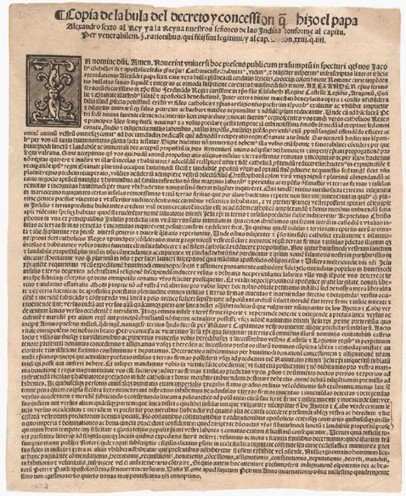

The Papal Bull of 1493 issued by Pope Alexander VI was a document that authorized the Spanish government to colonize, enslave and spread Catholicism using force if necessary. It was here when the Philippines was subjugated and brought under Spanish Crown, while the Muslims in the south fought to remain free.

The Papal Bull of 1493

1500

1543

First military victory of Buayan’n in Sarangani against the Villalobos Expedition of imperial Spain

June 1572

The Battle of Bangkusay between the young Macabebe Chief Tariq Sulayman and Miguel Lopez de Legazpi in June 1572. (by Dan H. Dizon in Center for Kampampangan Studies, Holy Angel University. Photo was provided by Ian Alfonso)

1578

Governor Francisco de Sande sent invasion troops in Brunei in and in Jolo and Magindanaw (Maguindanao), all but doomed into oblivion except for Brunei were de Sande occupied the Sultanate for a few months only after his Spanish and Indio (later Filipino) colonial troops were decimated by an herb-borne plague.

MAY 23, 1578

1578-1596 Second Stage of the Moro War

1578-1596

Expedition headed by Captain Gabriel de Ribera

1579

Invasion of the Rajahnate (Kerajaan) of Bwayan

April 25, 1596

1600

1600 - 1900

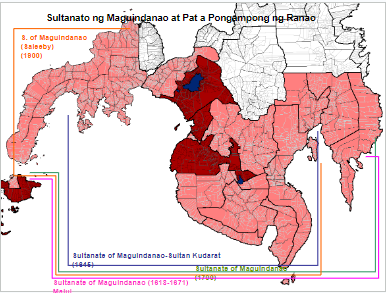

Sultanato ng Maguindanao at Pat a Pongampong ng Ranao

Maguindanao Treaty

September 8, 1605

Buayan-Spanish Treaty

March 1, 1609

1617

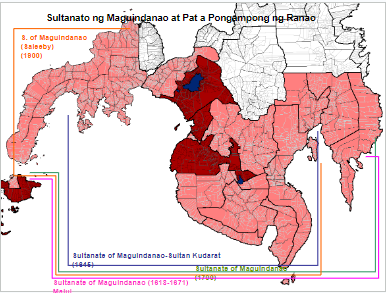

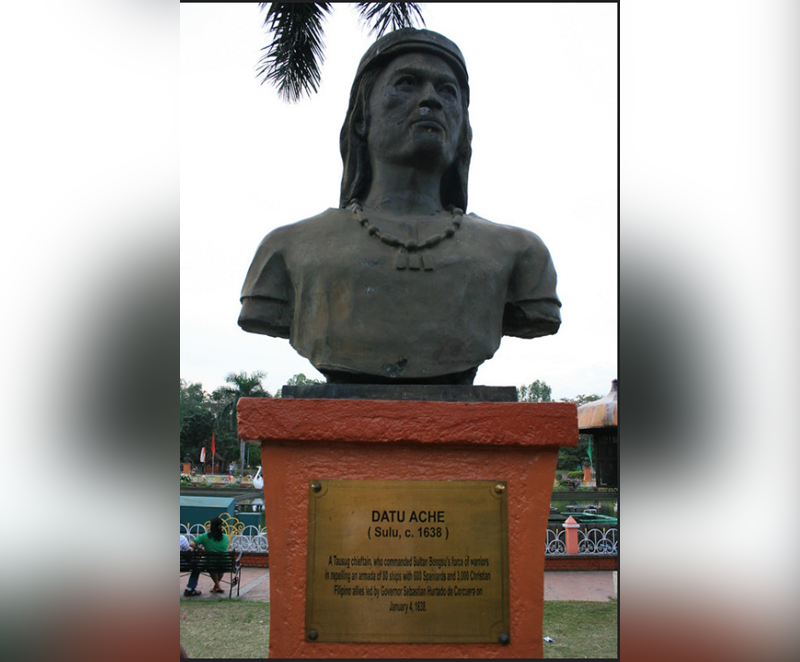

Datu Aceh: The Famed Warrior Earning the Wrath of Spanish Conquistadores

1627

Raja Bongsu: The Beginning of an Epic Battle

1638

The Epic Battle: Four-Month Siege of Jolo

Maguindanao Second Treaty

March 1639

Qudarat-Lopez Treaty

June 24, 1645

Bongsu-Lopez Treaty

April 14, 1646

Death of Qudarat

1671

The Capture of Lamitan Town

March 13, 1637

1700

The Sultan of Borneo made a cession of the north part of Borneo from Keemanees northward, with the island of Palawan, Banguey, Balambangan, etc to the Sooloos (Sulu).

1704

Cession of Balabak area in Palawan

1705

Sultan Bayan ul-Anwar capitulations of 1719

1719

Sultan Pakir Maulana Kamza Treaty

1734

1735-1775

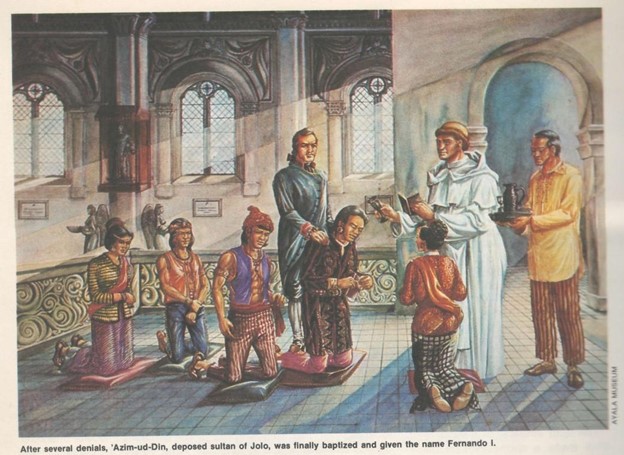

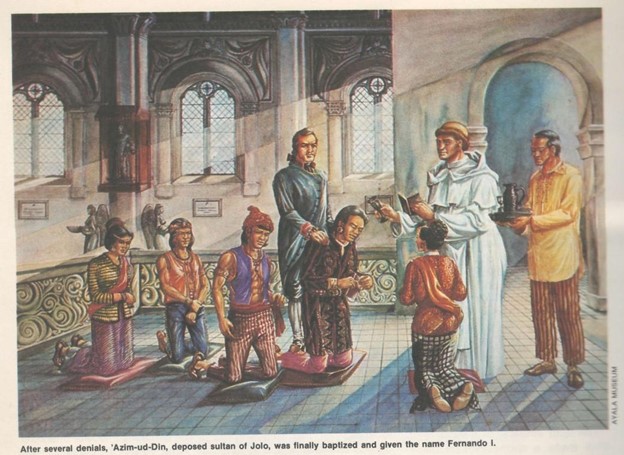

The Intriguing Story of Sulu Sultan ‘Azim ud-Din

1753

Sultan Mu‘izz ud-Din Sought Support from Chinese Emperor Against Spaniards

1775 Trade Agreement

1775

1789 and 1794 Treaties

1789 and 1794

1800

1805 Treaty of Alliance

November 4, 1805

Sultan Maitum Resuscitated the 212 Years (1619-1831) Eclipsed of the Rajahnate of Buayan

1831

1837 Treaty

1837

Treaty of Datu Dakula

May 20, 1843

Treaty Amity and Commerce

May 15, 1845

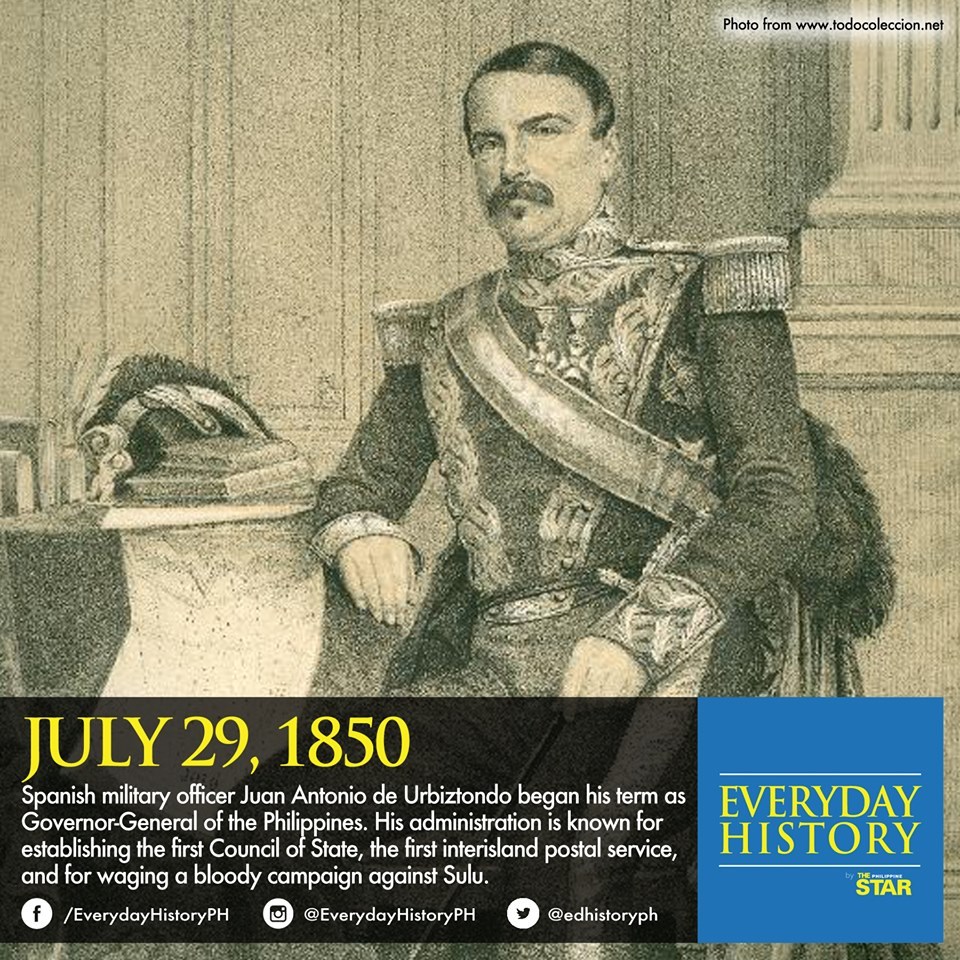

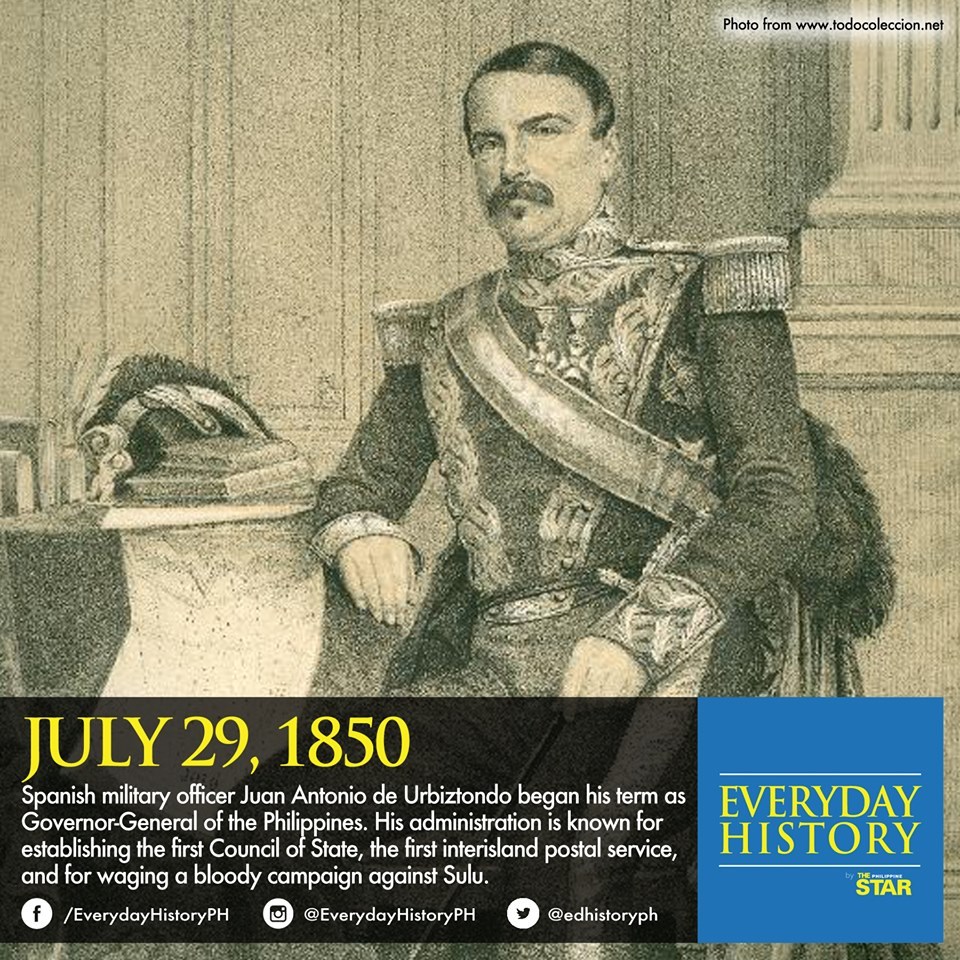

1850

Urbiztondo and the Friendship Treaty With Sulu

1861 Capitulations

1861

Peace Treaty 1875

1875

Treaty of Friendship

June 14, 1875

Buayan Capitulations

1887

Act of Adhesion

1888

Act of Conciliation

1888

Invasion of Maguindanao

January 1889

Invasion of Marawi

1895

June 12, 1898

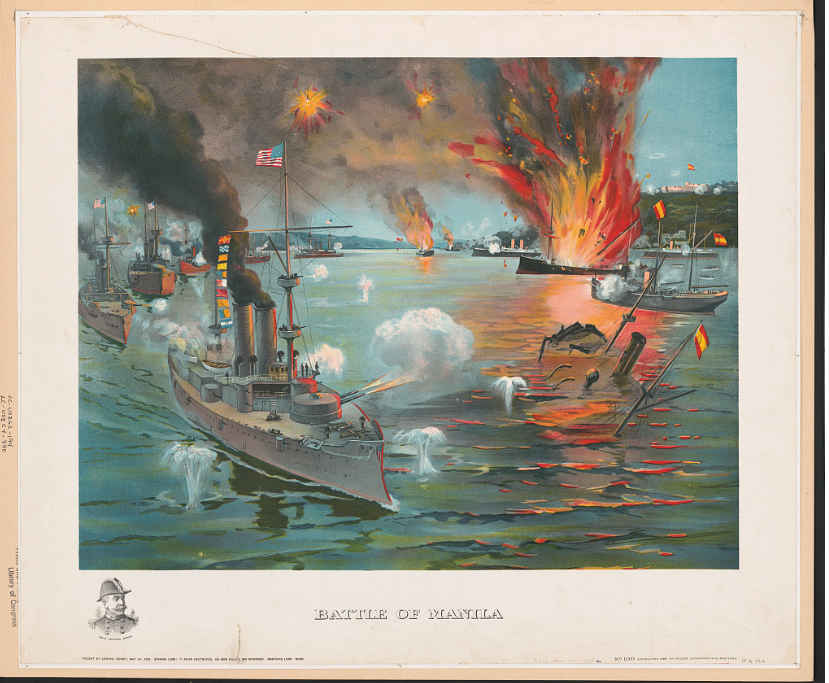

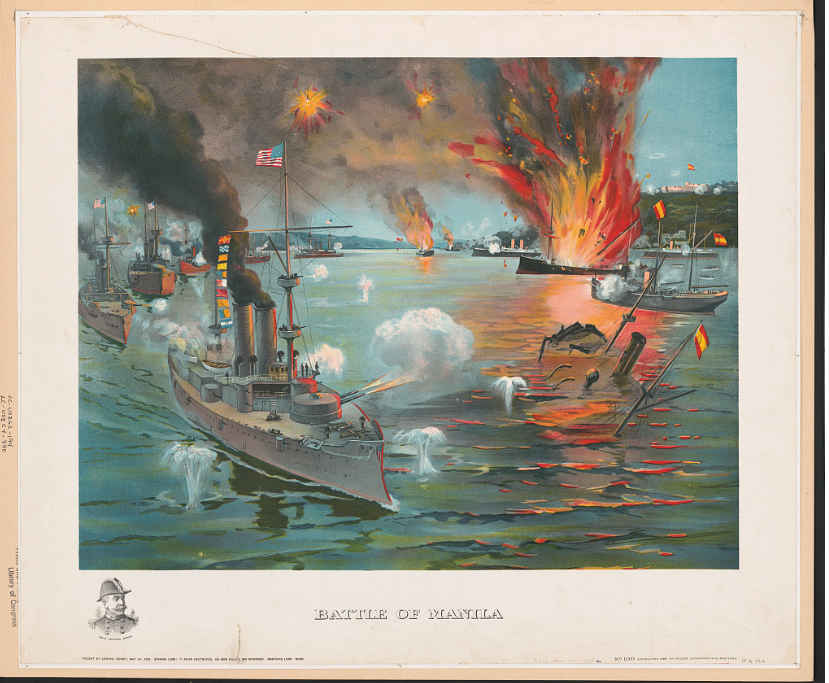

America’s Manifest Destiny and the 1898 Mock Battle of Manila Bay

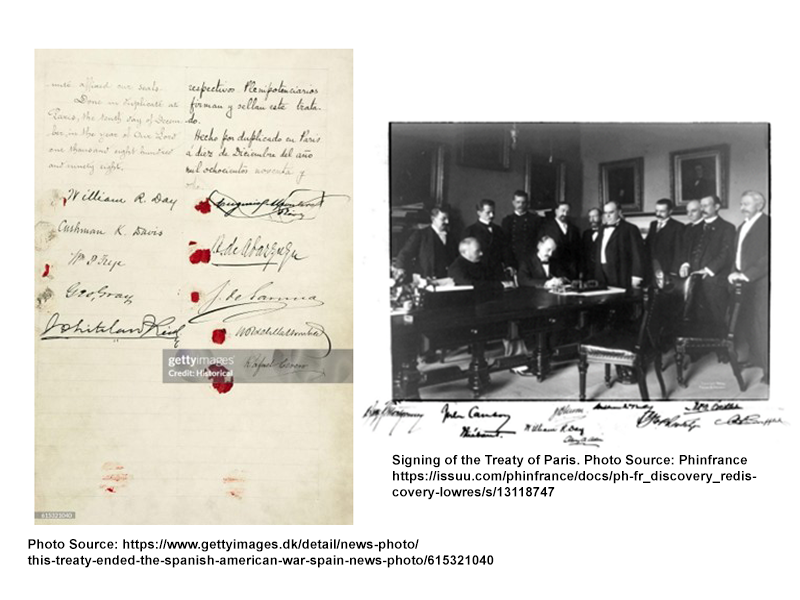

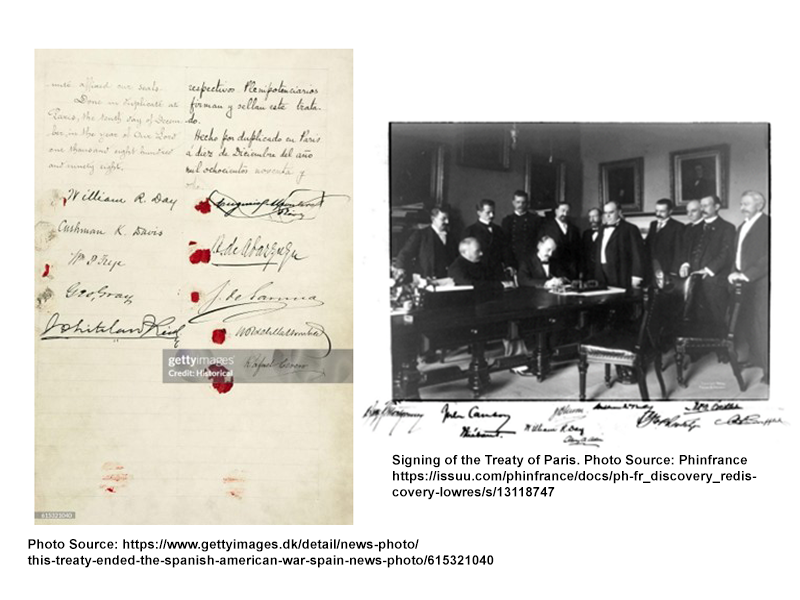

December 10, 1898

Treaty of Paris and the American Occupation of the Philippines

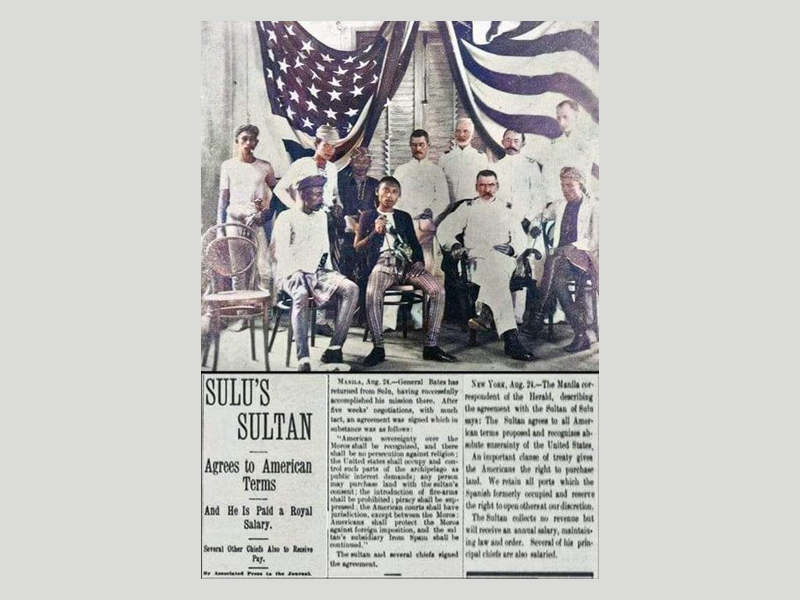

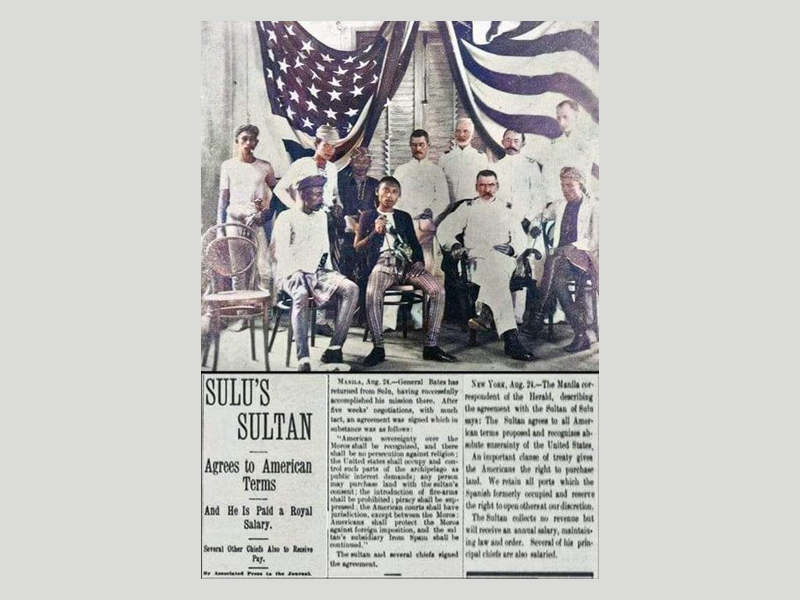

1899

The 1899 Kiram-Bates Agreement

1900

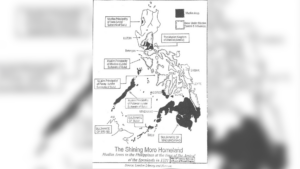

LUMAD ETHNOLINGUISTIC GROUPS, TRADITIONAL GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATIONS IN MINDANAO, CIRCA 1900

1900

Meranaw-American War 1902-1916

1902-1916

1901

Western Secular Education: America’s Tool for Colonization

Bangsamoro (Moro) lands were opened to settlers

1902

Creation of the MORO PROVINCE (1903-1913): The U.S. Instrument of Direct Rule

June 1, 1903

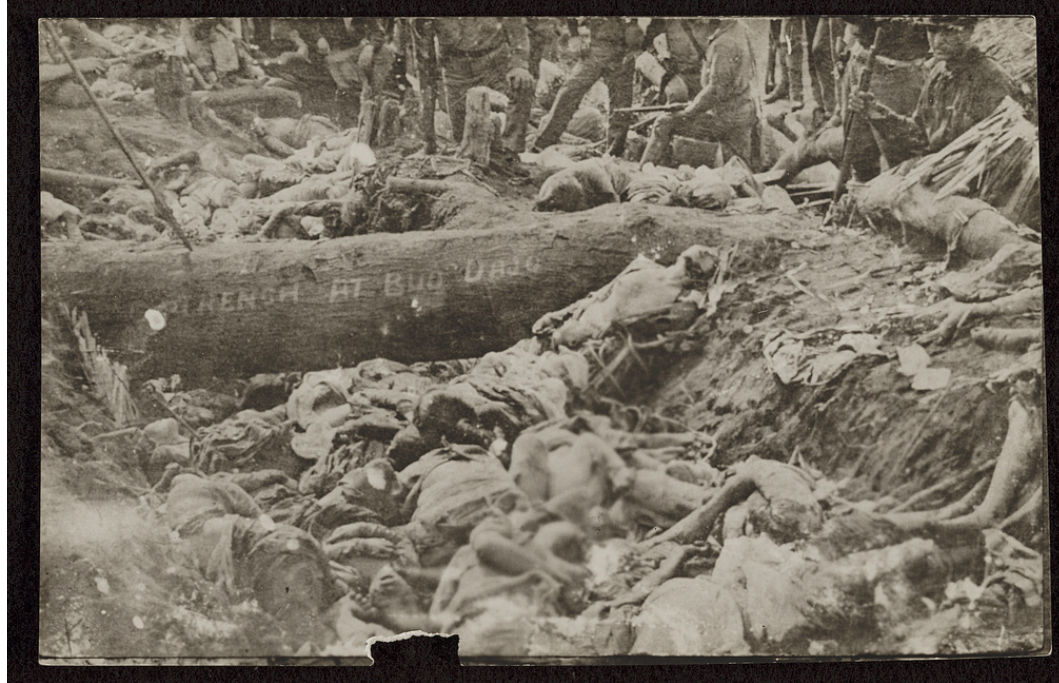

1903 - 1906

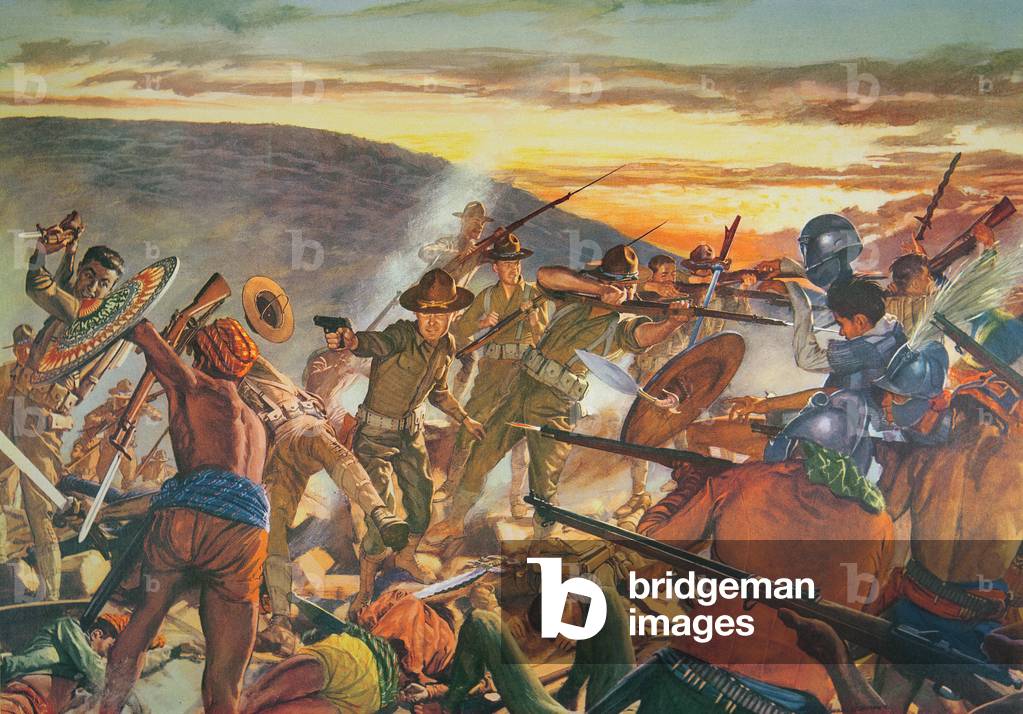

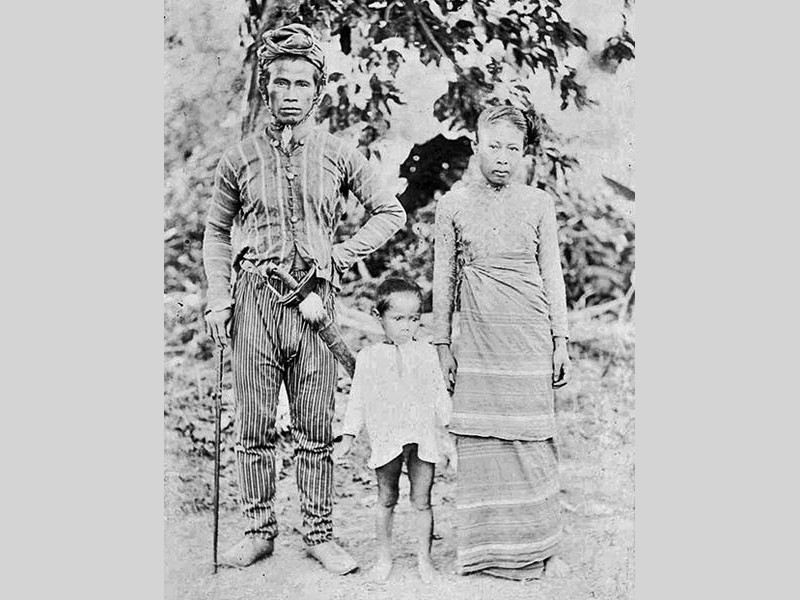

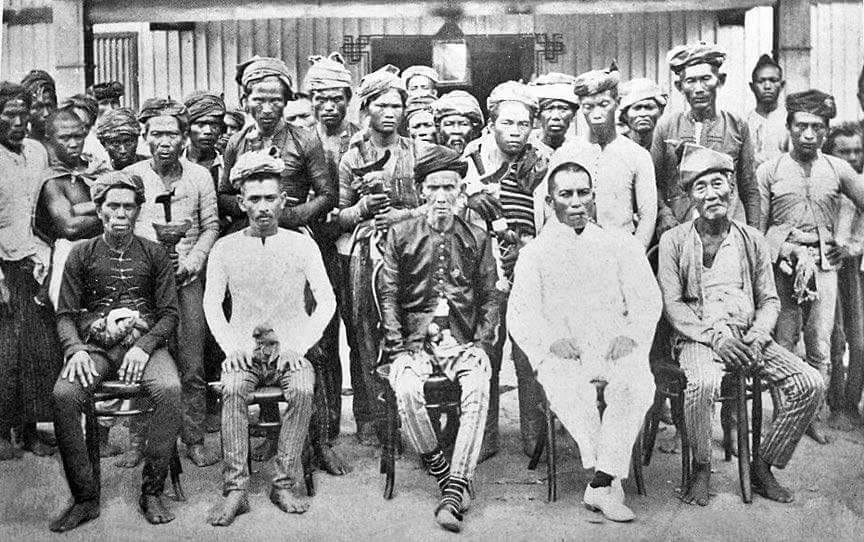

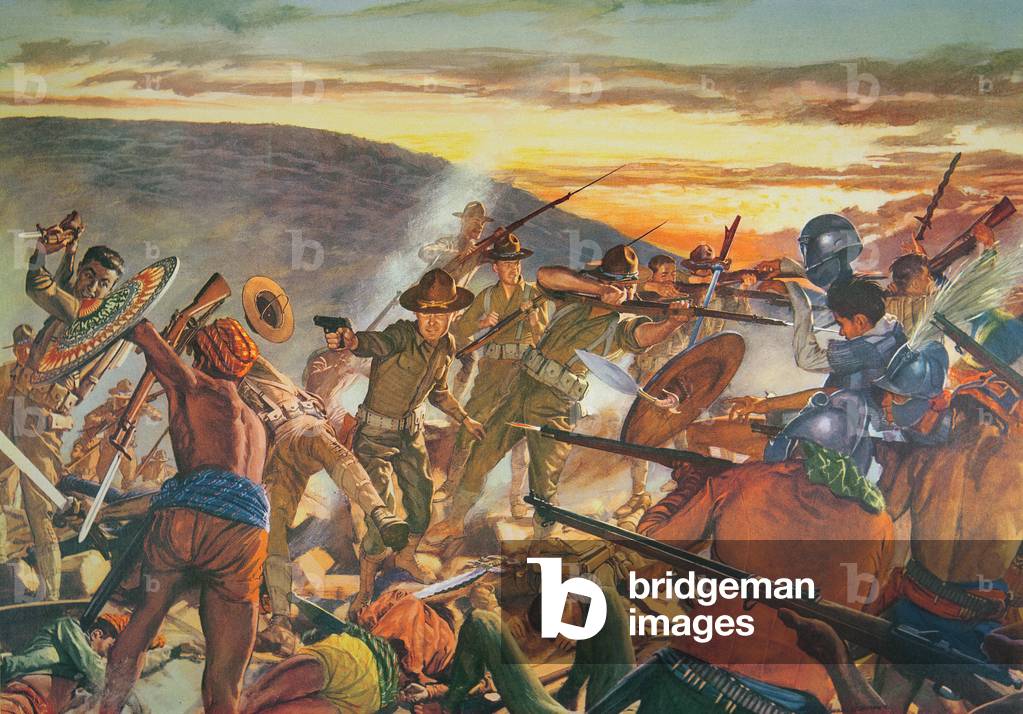

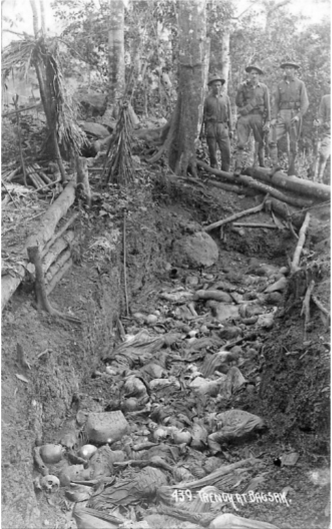

Panglima Hassan Uprising and the Battle of Bud Dahu

1903-1905

The Pursuit of Datu Ali in Cotabato

1910

Protestest Against Americans

Creation of Colonies

1912

1913

Battle of Bud Bagsak

DEPARTMENT OF MINDANAO SULU

MARCH 13, 1914 - FEBRUARY 5, 1920

Sulu Petition to U.S. Government

1921

1933

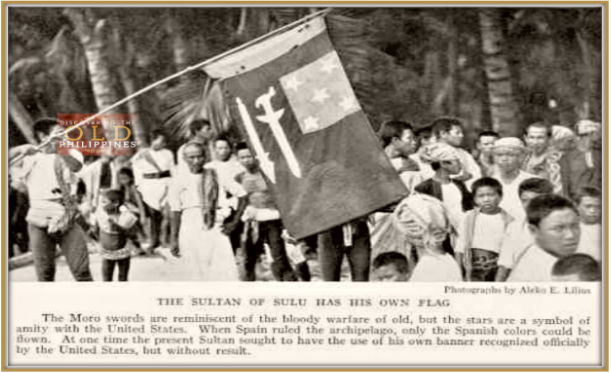

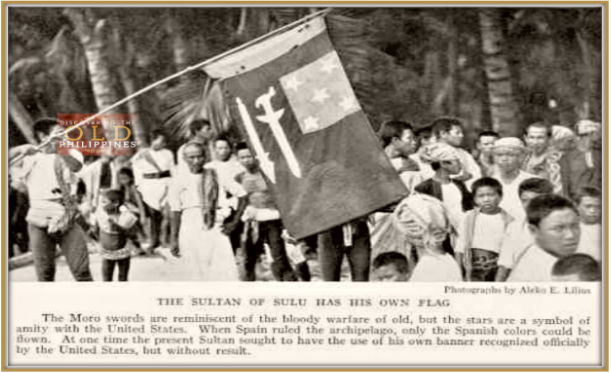

The Sultan of Sulu Has His Own Flag

Dansalan Declaration

1935

Japanese Imperial Army Invasion of Mindanao

December 8, 1941

July 04, 1946

1946 Philippine Independenc: A Separate People in a New Nation

1948

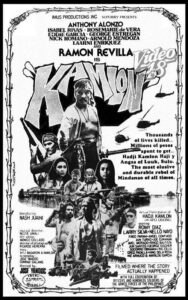

1948 Kamlun Uprising

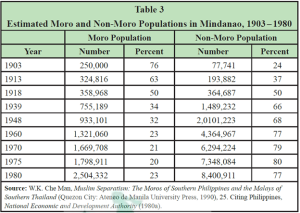

Resettlement - Republic of the Philippines

1949-1954

1961

Congress Bill for Sulu Independence

Resettlement - Part of RP Land Reform

1963-1971

1968

The 1968 Mindanao Independence Movement (MIM)

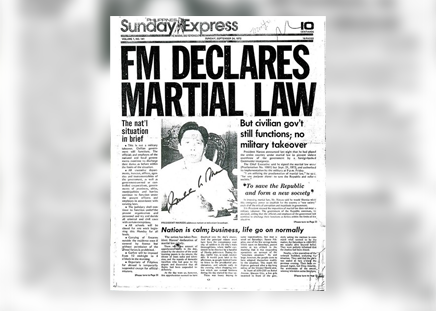

1972

JABIDAH, MISUARI, AND THE MORO NATIONAL LIBERATION FRONT (MNLF)

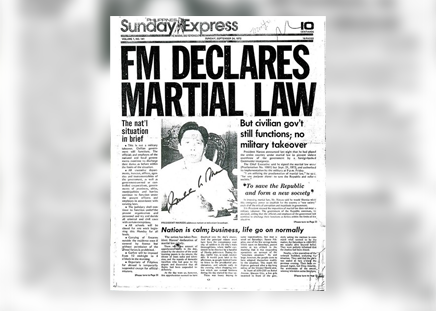

September 24, 1972

The Martial Law and All Out War in Mindanao and Sulu

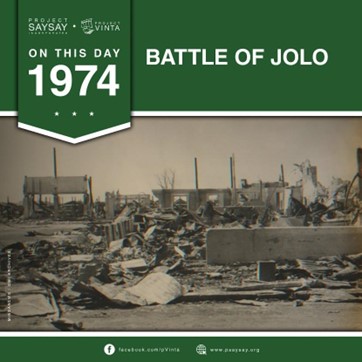

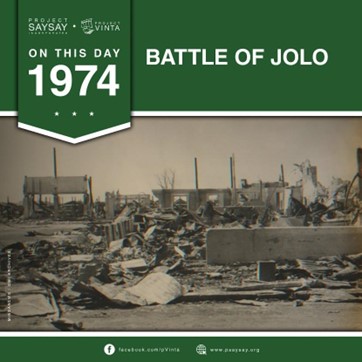

February 07, 1974

Battle of Jolo

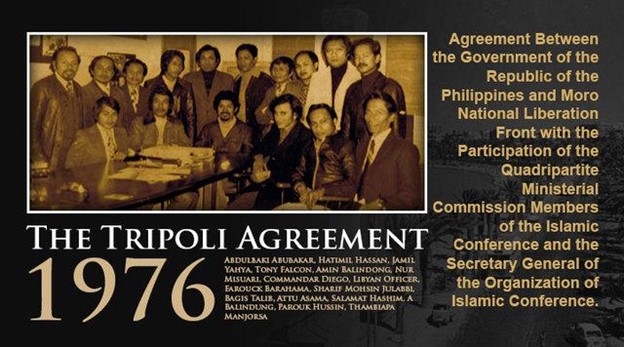

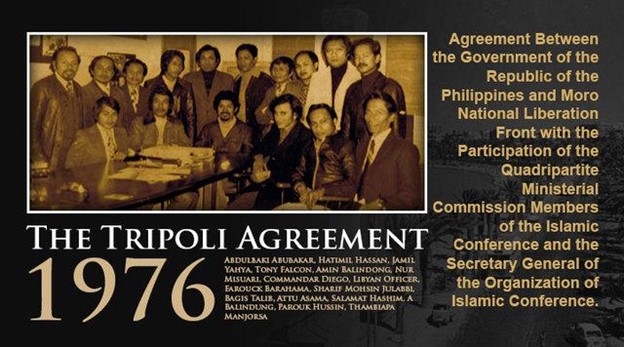

December 23, 1976

The Tripoli Agreement

1976

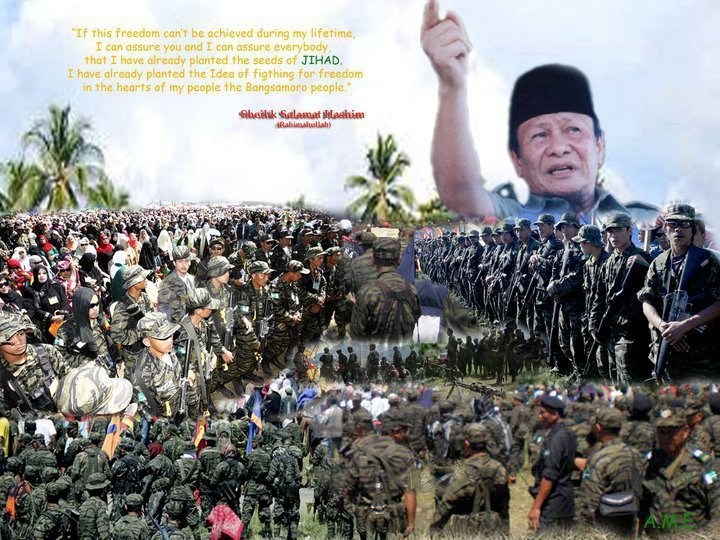

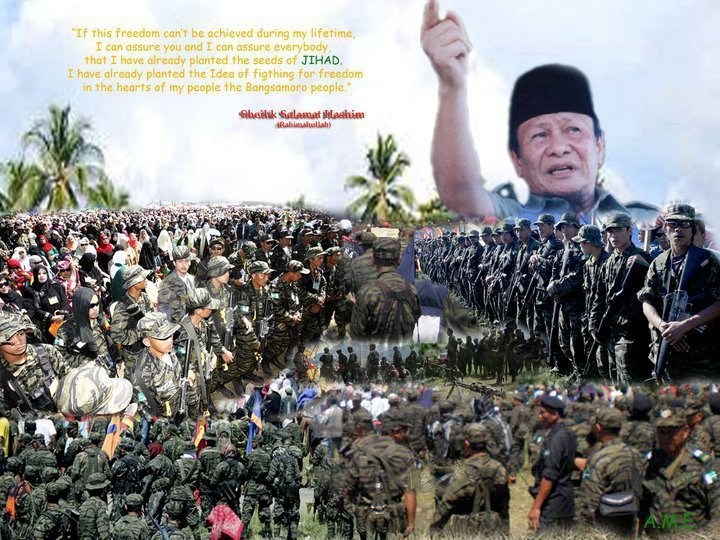

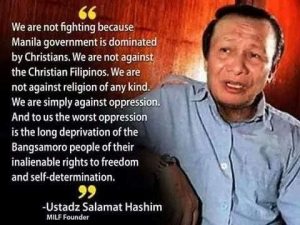

Ustadz Salamat Hashim and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

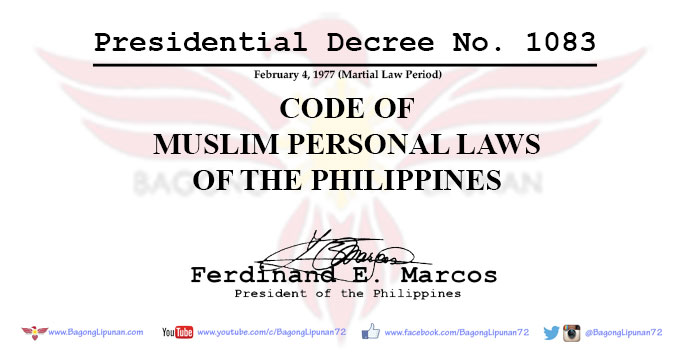

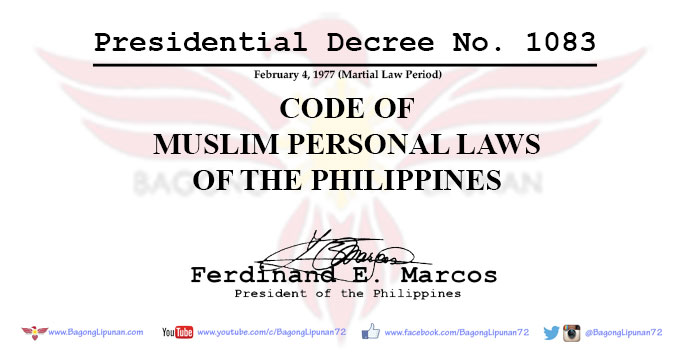

February 4, 1977

President Marcos’ Reconstruction and Reforms

1984

The Pat a Pengampong ko Ranaw

February 25, 1986

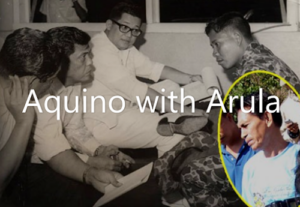

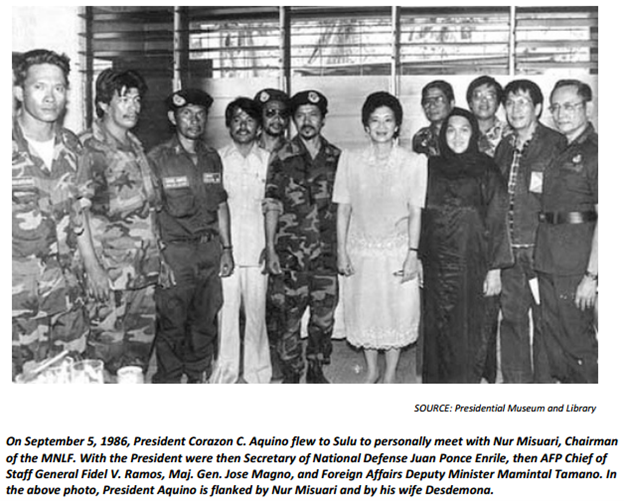

President Corazon Aquino and the Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao

The Rise of the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG)

1991

September 02, 1996

The 1996 Final Peace Agreement

2000

March 21, 2000

Estrada’s All Out War Against MILF

2001

ARROYO’S ALL OUT PEACE

2011

President Aquino’s Bangsamoro Basic Law and the Crises of Peace Talks

2015

MAMASAPANO INCIDENT – BBL Died with SAF 44

2016

President Duterte’s War and Peace Efforts

2017

The Birth of Maute-ASG Alliance and the 2017 Marawi Siege

July 26, 2018

President Duterte and the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region for Muslim Mindanao (BARMM)

September 15, 2022

BBM UNITY

Early Civilization 6810 - 3190 B.C.

6810

Prehistoric Period

Introduction Mindanao and Sulu had undeniably a flourishing civilization before the arrival of Islam. It was characterized by intricate social structures, vibrant cultures, and extensive trade with neighboring islands and distant lands that defined these ancient societies. The people of Mindanao and Sulu excelled in developing advanced agricultural practices, crafting remarkable artifacts, and constructing impressive megalithic structures that epitomized their ingenuity and resourcefulness. Their lives were deeply intertwined with the natural environment and were already exposed to a universalistic religion by the Indian sages and Chinese monks. The impact of Islam’s arrival in the twelfth century on early civilization was...Introduction

Mindanao and Sulu had undeniably a flourishing civilization before the arrival of Islam. It was characterized by intricate social structures, vibrant cultures, and extensive trade with neighboring islands and distant lands that defined these ancient societies. The people of Mindanao and Sulu excelled in developing advanced agricultural practices, crafting remarkable artifacts, and constructing impressive megalithic structures that epitomized their ingenuity and resourcefulness. Their lives were deeply intertwined with the natural environment and were already exposed to a universalistic religion by the Indian sages and Chinese monks.

The impact of Islam’s arrival in the twelfth century on early civilization was undeniable. Islam introduced monotheism as a religious belief, social structure, and political system, establishing the sultanates of Sulu and Maguindanao. These sultanates bolstered trade with neighboring Muslim regions, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and culture, thus enriching the civilization in Mindanao and the entire Sulu archipelago. This exchange led to the development of written language and literature, as Arabic script was adopted for local languages, enriching the cultural landscape and preserving historical records and religious texts. The introduction of Islamic education systems, including madrasahs, promoted literacy and scholarly pursuits, further propelling the intellectual development of Mindanao and Sulu.

In summary, gaining insight into the early civilization of Mindanao and Sulu is crucial for understanding the rich reservoir of history of the Bangsamoro people, showcasing the depth and diversity of its pre-Islamic heritage. On the contrary, Islam significantly impacted early civilization in Mindanao through political centralization, heightened trade, cultural enrichment, and educational advancement, laying a sturdy foundation for the region’s subsequent historical and cultural identity.

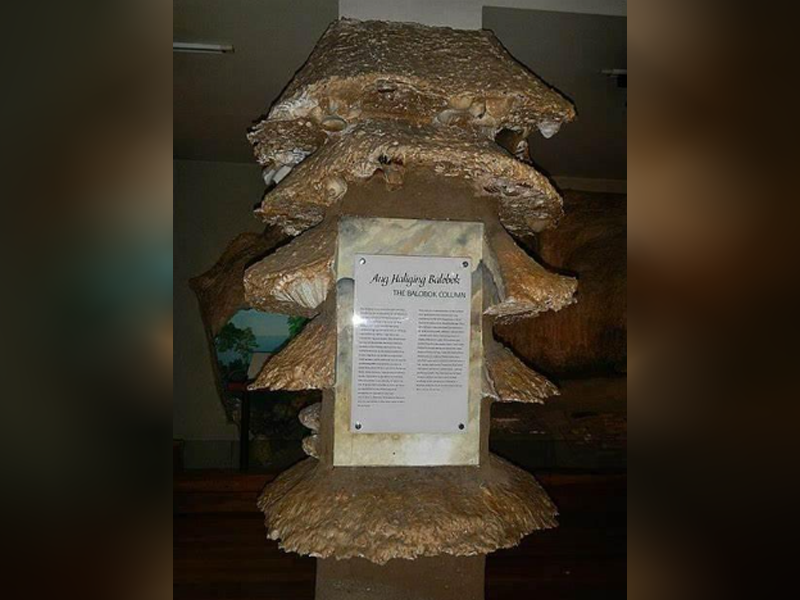

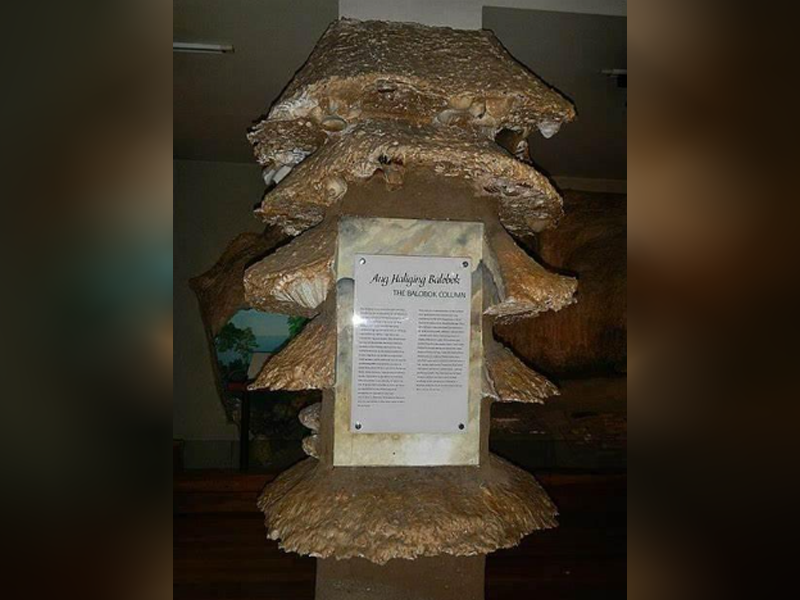

(A reconstruction of the cultural and geological layers found within the Balobok Rock shelter. Original photo to be obtained from the National Museum of the Philippines)

Balobok Archeological Site or Balobok Rock Shelter in Tawi-Tawi, a location of prehistoric habitation around 6810-3190 BCE (5760-5140 years ago), was considered one of the earliest human settlement zones in Southeast Asia which yielded early evidence of human presence in Mindanao.

The existence of the Balobok Rock Shelter in Bongao, Tawi-Tawi, Philippines, was reported in 1966. The initial excavation activity followed this discovery in late 1966 up to 1969, and a re-excavation in 1992 and 2007. Here, archeologists found polished shell adzes made from Tridacna gigas, flaked tools, polished stones, earthenware sherds with lime-impressed designs, and bone tools, demonstrating humans’ ability to create and use tools during that era. The recovery of these materials suggests that the site may have played a significant role in early people’s movements into the Southwest Pacific and to the Pacific World. In the 1970s, during the war participated by the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), the cave also served as the combatants’ natural shelter.

Due to its historical relevance, Bangsamoro lawmakers lodged a bill declaring the Balobok Cave in Bongao, Tawi-Tawi as a heritage zone through the Bangsamoro Transition Authority Bill No. 197, also known as the “Balobok Cave Preservation Act of 2020”. With this, the Bangsamoro Commission for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (BCPCH) and the Environment Ministry would be responsible for administering the protection, development, and promotion of the Balobok Cave.

Sources:

Cayon, Manuel. 2023. “Bangsamoro Parliament bill declares Balobok Cave in Bongao, Tawi-Tawi, a heritage site.” businessmirror.com.ph. https://businessmirror.com.ph/2023/01/06/bangsamoro-parliament-bill-declares-balobok-cave-in-bongao-tawi-tawi-a-heritage-site/.

HistoryLearning.com. 2024. History Learning Balobok Archeological Site. https://historylearning.com/history-of-the-philippines/pre-history/balobok-archaeological-site/.

National Museum of the Philippines. 2022. Balobok Rockshelter. https://www.nationalmuseum.gov.ph/2022/06/28/balobok-rockshelter/.

(Ventral and Dorsal surfaces of Obsidian collected during the archeological survey at Kuta Tuka Inudaran in Lanao del Sur. Photo by: University of the Philippines School of Archaeology)

Caption: Obsidian, used as stone tools during the Terminal Pleistocene in Ille Cave (Palawan) and Bubog I (Ilin Island, Mindoro) discovered in Lanao del Sur, highlights the advanced maritime trade and mobility of the “Celebes Seafaring People” around 6000-5000 BP.

Short Narrative: The obsidian found in Lanao del Sur is evidence of the active trade and mobility of ancient peoples, known as the “Celebes Seafaring People,” around the Celebes region circa 6000-5000 BP. These people had advanced boat-building and navigational skills, facilitating a vast maritime trading network. Chemical analysis indicates that obsidian in Lanao del Sur originated from Bukidnon, supporting the hypothesis of this maritime network during the Neolithic Period. This period (6000-4000 BP) saw significant movement, agriculture, and pottery introduction, suggesting a shared cultural affiliation among island Southeast Asian communities. The “Celebes Seafaring People” hypothesis aligns with historical theories by Francisco Combes and Fay-Cooper Cole about migration patterns from Indonesia to Mindanao, suggesting a complex maritime exchange and migration network that needs further investigation.

Sources: Neri, Lee Anthony M, Juvanni A Caballero, Rona Catherin R Repancol, Ruben Claro A Reyes, and Jay Rone F Acasio. The Archaeology of Lanao del Sur: Probing the M’ranao-Chinese Relations Before 1898. Quezon City: University of the Philippines School of Archeology, 2023.

Read More

Indian Link and Influences

800AD - 1365

Indian Link and Influences

Before Islam arrived, Sulu and Mindanao were actively involved in the international sea trade, which facilitated the entry of Indian and Chinese traders and sages, who brought with them their culture, system of government, and religious ideas. More information: “The first Indian immigrants into the region seem to have been chiefly of the old Vedic faith, mixed with primitive nature and sun worship, although Buddhistic ideas became dominant in the early centuries of the Christian era. Indian traders and colonizers of these types seem to have entered the Philippines through Eastern and Northern Borneo. They continued to drift from...Before Islam arrived, Sulu and Mindanao were actively involved in the international sea trade, which facilitated the entry of Indian and Chinese traders and sages, who brought with them their culture, system of government, and religious ideas.

More information:

“The first Indian immigrants into the region seem to have been chiefly of the old Vedic faith, mixed with primitive nature and sun worship, although Buddhistic ideas became dominant in the early centuries of the Christian era. Indian traders and colonizers of these types seem to have entered the Philippines through Eastern and Northern Borneo. They continued to drift from about the twelfth and thirteenth century. The second wave of Indian influences with Brahmanic character entered the Philippines at the height of the Madjapahit Empire in the fourteenth century.”

Sources: Beyer, Henry Otley. 1948. “Early History of Philippine Relations with Foreign Countries, Especially China,” Historical Introduction to E. Arsenio Manuel, Chinese Elements in the Tagalog Language. Manila: Filipiniana Publications.

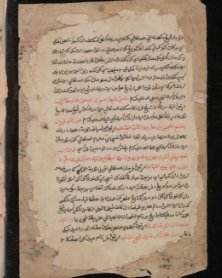

The 1365 Negarakretagama Manuscript listed Sulu as part of the Madjapahit spheres of influence. From Sulu, Indians managed to penetrate mainland Mindanao.

Source: National Library of Indonesia.

More information:

The Negarakertagama is an Old Javanese eulogy written by a Buddhist monk, Empu Prapanca, around 1350-1389 for Hayam Wuruk, a Javanese king of the Majapahit. The manuscript talks about the history of the Hindu Empire, Majapahit (1293-1527 AD) and its dominion where Sulu was included. Based in Sumatra, the empire was founded by Kerjarajasa Jayawarddhana, locally known as Raden Wijawa, in 1293. Its peak of influence was reached during the reign of Hayam Wuruk.

Negarakertaga was named The Memory of the World by UNESCO in May 2008 and registered as a World Heritage in 2013.

Sources: Prapanca,Mpu. 2017. Negarakertagama Kawi: In Kawi Script. USA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

The first book on the History of Sulu, written by a Lebanese American scholar Najeeb Saleeby whom the American government commissioned to study the Muslims in Sulu and Mindanao. He wrote that the names of Sulu’s ancient rulers, Jaimun Kulisa (God of Vedic Pantheon) and Indira (Goddess of Rain) Suga, were of Sanskrit origin.

Source: Saleeby, Najeeb M. 1908. The History of Sulu. Manila Bureau of Printing.

More information:

Prior to this, at the height of the Srivijaya Empire in the ninth century, with Banjarmasin as its seat of power, they sent a colony to Sulu to drive out the Orang Dampuans (Champs) so they could control the pearl industry. To gain the trust of the Tausugs, they offered their princess to the local chief for marriage. The rajas (pre-Islamic rulers of Sulu) descended from this marriage alliance. According to the Sama people in this area, there was also a kingdom on a hill located on the eastern plains of Bud Tua in Dungan in Tawi-Tawi. Before the end of the tenth century, Buddhist Banjars introduced kingdoms under rajaship and datuship in Sulu and the Philippines.

Srivijaya was a Buddhist thalassocrat empire based in Sumatra that reigned from the seventh to the eleventh century.

Sources:

Ututalum, Sururul-Ain and Abdul-Karim Hedjazi. 2002. The Rise and Fall of the Sulu Islamic Empire (1675-1919). USA: Professional Press.

Kurais II, Muhammad. The History of Tawi-Tawi and Its People. 1979. Tawi-Tawi: Mindanao State University Sulu-College of Technology and Oceanography.

Hunt, J. 1967. Some Particulars Relating to Sulo in the Archipelago of Felicia. In Notices, of the Indian Archipelago and Adjacent Countries, edited by J. H. Moor. London: Cass Publishers.

Darangen is an ancient epic song of the Maranaos that reveals the traditional knowledge of Lanao during the pre-Islamic era.

More information:

A total of 72,000 lines in 17 cycles, the Darangen celebrates episodes of M’ranao history, customary law, standards of social and ethical behavior, aesthetic beauty, the tribulations of mythical heroes, and many other themes. In 2005, the National Commission for Culture and the Arts declared it a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity,” They were inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity 2008. The tales of Maharadia Lawana and Prince Bantugan, as depicted in the famous Singkil dance, are the localized versions of the Ramayana, a popular epic of India. Similar Indian influence can also be found in the Maguindanao folktale Indapatra, Solayman, and the Sagayan Dance.

Sources:

Saber, Mamitua . 1961. Darangen: The Epic of the Maranaws. Philippine Sociological Review, January-April, Vol. 9, No. 1/2 (January- April 1961), pp. 42-46 Published by: Philippine Sociological Society

https://www.jstor.org/stable/43498156

Francisco, Juan. 1977. “Indian Imprint” in Filipino Heritage, vol.3. Quezon City: Lahing Pilipino Publishing Inc. p.576-79.

https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/darangen-epic-of-the-maranao-people-of-lake-lanao-00159

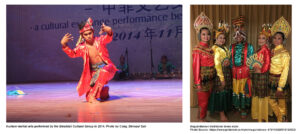

Pangalay and Igal of the Tausug and Sama, Singkil of the M’ranao, and Sagayan of the Maguindanao are celebrated traditional dances of Indian influence via the Malay world.

More information:

The Pangalay dance of the Tausug, which is called Igal among the Sama of Tawi-Tawi, is meditation in motion. The various and endless movements of the hands derived from the stillness of the mind reflect how God created the world of nature in various forms. Singkil of the M’ranao and Sagayan of Maguindanaon are royal dances derived from an episode of the Darangen epic of Bantugan, a M’ranao prince. Singkil was listed as one of the Bayanihan’s Signature Dances of the Philippines. Sagayan dance among the Maguindanaon is also performed to welcome good fortune and drive away bad spirits.

Sources:

Namiki, Kanami. 2011. “Hybridity and National Identity: Different Perspectives of Two National Folk Dance Companies in the Philippines.” Asian Studies: Journal of Critical Perspective on Asia. Vol. 47. https://www.asj.upd.edu.ph/mediabox/archive/ASJ-47-2011/namiki.pdf

Kasim, Osmeña M. (2021. “Appreciation Level on Maguindanaon Dances and their Cultural Presentation.” International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR) Volume 59, No 1, pp 188-201.

Pandita, a Sanskrit-based word referring to a learned man, especially among the Maguindanaon, was the most important figure in Philippine Muslim Society.

More information:

Indian sages introduced a universalistic tradition that elevated the religious understanding of the natives and prepared them for the arrival of Islam. Some religious words like agama (religion), puasa (abstinence), narka (hell), surga’ (heaven), pahala (reward), bartapa/balatupa (seclusion in the mountain), and many others which are of Sanskrit origin are being used by all Muslims in Mindanao and Sulu until today.

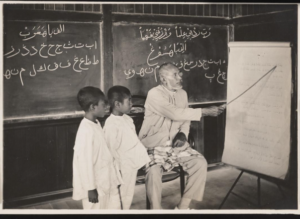

Panditas who were learned in religion and spirituality, were responsible for preserving Islam until the American occupation. American authorities reported that pandita schools operating in Mindanao were a major hindrance to the introduction of Western secular education. The panditas were also military opponents of Western colonial rule since the Spanish period. They not only encouraged the natives to wage jihad against the conquerors but also participated in the military defense of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago.

Sources:

Absari, Darwin J. PagTuhan: The Tausug Spiritual Tradition. 2021. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Baldoza, Jonathan Victor. The Panditas of the Philippines, 17th – Early 20th Centuries. Archipel [Online], 103 | 2022, Online since 30 August 2022, accessed on 12 September 2022. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/archipel/2969

Gowing, Peter Gordon. 1983. Mandate in Moroland: The American Government of Muslim Filipinos. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Milligan, Jeffrey Ayala. 2020. Islamic Identity, Postcoloniality, and Educational Policy: Schooling and Ethno-Religious Conflict in the Southern Philippines. Singapore: Springer Nature.

Read More

What the Muslims Learned from Their Long Interaction with the Chinese

800 - 1365

What the Muslims Learned from Their Long Interaction with the Chinese

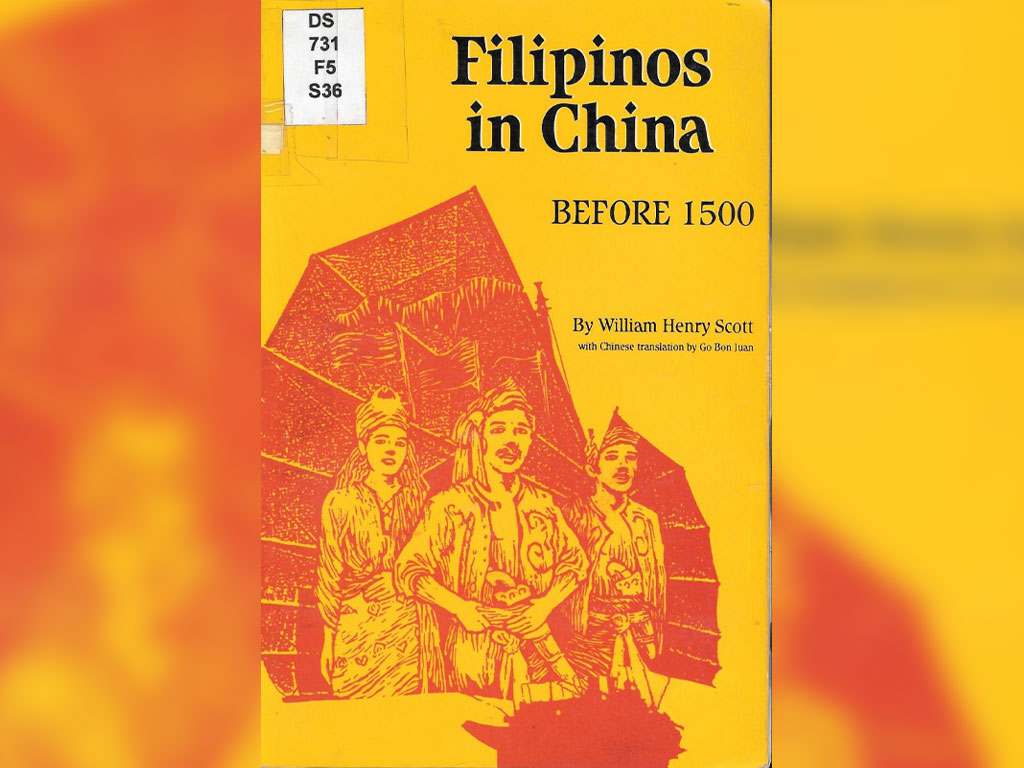

Photo cover of the book written (designed?) by Henry William Scott published by De La Salle University in 1989 The book reveals valuable information on the early interactions between China and the Philippines, including the Sulu Archipelago and Mindanao, before 1500. More information: Tang ceramics and dynasty coins found in Sulu and Basilan reveal the possible earliest contact with China during the late Tang Dynasty. However, it was only in the eleventh century that Chinese junkers started to visit Sulu. In 1206, Basilan was already exporting cotton to China. During the Yuan Dynasty, Sulu appeared in official Chinese records....

The book reveals valuable information on the early interactions between China and the Philippines, including the Sulu Archipelago and Mindanao, before 1500.

More information:

Tang ceramics and dynasty coins found in Sulu and Basilan reveal the possible earliest contact with China during the late Tang Dynasty. However, it was only in the eleventh century that Chinese junkers started to visit Sulu. In 1206, Basilan was already exporting cotton to China. During the Yuan Dynasty, Sulu appeared in official Chinese records. This contact with the Chinese was accelerated during the Ming Dynasty with the tribute missions by Sulu and Mindanao rulers at the height of the reign of the sultanates.

Sources:

Scott, William Henry. 1989. Filipinos in China before 1500. China Studies Program. Manila: De La Salle University.

Magdalena, Federico V. The Chinese in Moro Land. Philippine Association for Chinese Studies. https://www.pacs.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Chapter-2-The-Chinese-in-Moroland-by-Federico-V.-Magdalena.pdf

Ututalum, Sururul-Ain and Abdul-Karim Hedjazi. 2002. The Rise and Fall of the Sulu Islamic Empire (1675-1919). USA: Professional Press,.

Patanne, E. P. 1996. The Philippines in the 6th to 16th Centuries. San Juan, Metro Manila: LSA Press.

Two important historical landmarks that keep the Sulu and Mindanao link with China alive. The tomb of Sulu ruler Paduka Batara in China and the grave of Poon Tao Kong in Sulu.

More information:

The visit of Admiral Pei Pei Hsien, popularly known as Poon Tao Kong to the Tausug in Sulu sometime in 1410 inspired the three rulers, Paduka Batara, Kamaluddin, and Paduka Brabu to pay tribute to China in 1417. This tribute mission brought Mindanao and Sulu to an intimate and intensive trade with China. In December of the same year, Chinese Emperor Yongle dispatched High Commissioner Chang Ch’ien to the Philippines to bring Kumalalang, Mindanao, into line. In 1420, King Kanlai Ipentun of Kumalalang, Mindanao, paid tribute to China. More and more Chinese came to the Sulu Archipelago and Mindanao to live with the natives and found a second home there. At challenging times, Sulu and Mindanao became their refuge. For example, in 1758, thousands of Chinese fled to Sulu to escape persecution by the Spaniards. Dulawan in Maguindanao was the center of trade from which they penetrated Lanao’s heartland. Chinese artifacts recently found in Lanao suggest their presence in the area.

Chinese long stays in the Sulu Archipelago and Mindanao also resulted in cultural and philosophical exchanges. Many of their legacies, such as dress style, martial arts, culinary habits, and wedding and burial rights, continue to survive among the Muslims in Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago.

Sources:

Scott, William Henry. 1989. Filipinos in China before 1500. China Studies Program. Manila: De La Salle University.

Absari, Darwin J. 2021. PagTuhan: The Tausug Spiritual Tradition. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Chu, Richard T. (Ed). 2015. More Tsinoy Than We Admit: Chinese-Filipino Interactions Over the Centuries. Quezon City: Vival Foundation.

Kuntaw is a celebrated martial art practiced by Muslims across Sulu and Mindanao. It is derived from the words Kung (skill) of Kung Fu and Tao (the Way) of Taoism. It is a localized version of the Chinese martial art Tai Chi.

Source: Absari, Darwin J. 2021. PagTuhan: The Tausug Spiritual Tradition. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Another Chinese influence among the Muslims in the Philippines is their traditional dress style especially the preference for yellow color for the royalty dress of the Tausug, Maguindanaon, and M’ranao. Chinese remains famous in many of the traditional dresses of Muslims. In Sulu, the word Dasu Lannang (Chinese silk) is still used today.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar Adib. 1977. “Celestial Traders in Sulu.” In The Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation, vol.3, edited by Alfredo R. Roces, 592. Manila: Lahing Pilipino Publication.

Absari, Darwin J. “Lannang Sug: The Long History of Chinese in Sulu.” Research funded by the Ateneo Confucius Institute. Forthcoming.

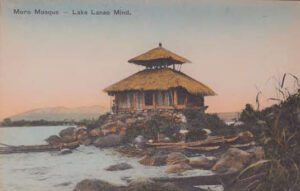

Chinese influence is even visible in the old pagoda-style mosques in Mindanao and Sulu.

More Information:

Chinese has also participated in the spread of Islam to Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago. In Sulu, a certain Makhdum Aminulla, who possibly arrived after karimul Makhdum, is said to have been accompanied by a Chinese Muslim Huy-Huy (Hue). The design of the original pillars in Tubig Indangan, Simunul in Tawi-Tawi is believed to have been carved by a Chinese Muslim. Design of old mosques in Mindanao and the Sulu archipelago as well as those of other countries in Southeast Asia is inspired by the Chinese pagoda.

Sources:

Majul, César Adib. Muslims in the Philippines. 1999. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Ta Sen, Tan. 2009. Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Read More

Further Spread to Luzon and Visayas

982

Further Spread to Luzon and Visayas

Description: The earliest presence of Muslims in the country was in 982 AD in Mindoro according to Chinese source. The beginning of spread of Islam to Luzon and Visayas however took place at the height of Sulu Sultanate and was reinforced by Bornean preachers in the 16th century. More information: As early as 982 AD, there was already presence of Islam in Luzon. Chinese document mentions an Arab Ship from Mindoro that went to China. But the initial spread of Islam to Visayas and Luzon took place at the height of Sulu Sultanate in the beginning of 15th Century. Some...Description: The earliest presence of Muslims in the country was in 982 AD in Mindoro according to Chinese source. The beginning of spread of Islam to Luzon and Visayas however took place at the height of Sulu Sultanate and was reinforced by Bornean preachers in the 16th century.

More information: As early as 982 AD, there was already presence of Islam in Luzon. Chinese document mentions an Arab Ship from Mindoro that went to China. But the initial spread of Islam to Visayas and Luzon took place at the height of Sulu Sultanate in the beginning of 15th Century. Some areas in Luzon and Visayas were under the control of Sulu Sultanate.

This initial spread was later reinforced when Brunei Sultan took over Manila and brought in Muslims Missionaries who reached as far Batangas, Cebu, Mindoro, Oton in Iloilo, Bonbon in Butuan. Spanish Historian Antonio Morga wrote, “If the entrance of the Spaniards had been longer delayed, this sect would have extended all over the island, and even throughout the others; and it would have been difficult to have uprooted it from them.”

However, the slow spread of Islam to Luzon and Visayas was halted with the arrival of Spaniards in mid-16th century. However, legacies of Islam continue to survive in language (simba, pangadji, hukum, asal, etc), and psychology (kapwa, ginhawa, saliksik, kasaysayan etc) of the Christianized natives. Even the Spaniards brought with them their Islamic roots as they have been Islamized by the Moors for nearly 800 years. Some Spanish loan words in the Tagalog like Alcalde and many others originated from Arabic.

Sources:

Donoso, Isaac. Islamic Fareast: Ethnogenesis of Philippine Islam. University of the Philippines Press, 2013.

More Islamic Than We Admit. Insights into Philippine Cultural History. Edited by Isaac Donoso. Quezon City: Vival Foundation, Inc. 2018.

Majul, Cesar A. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1999.

Scott, Henry William. PreHispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History

(Revised Edition). Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 1984.

Read More

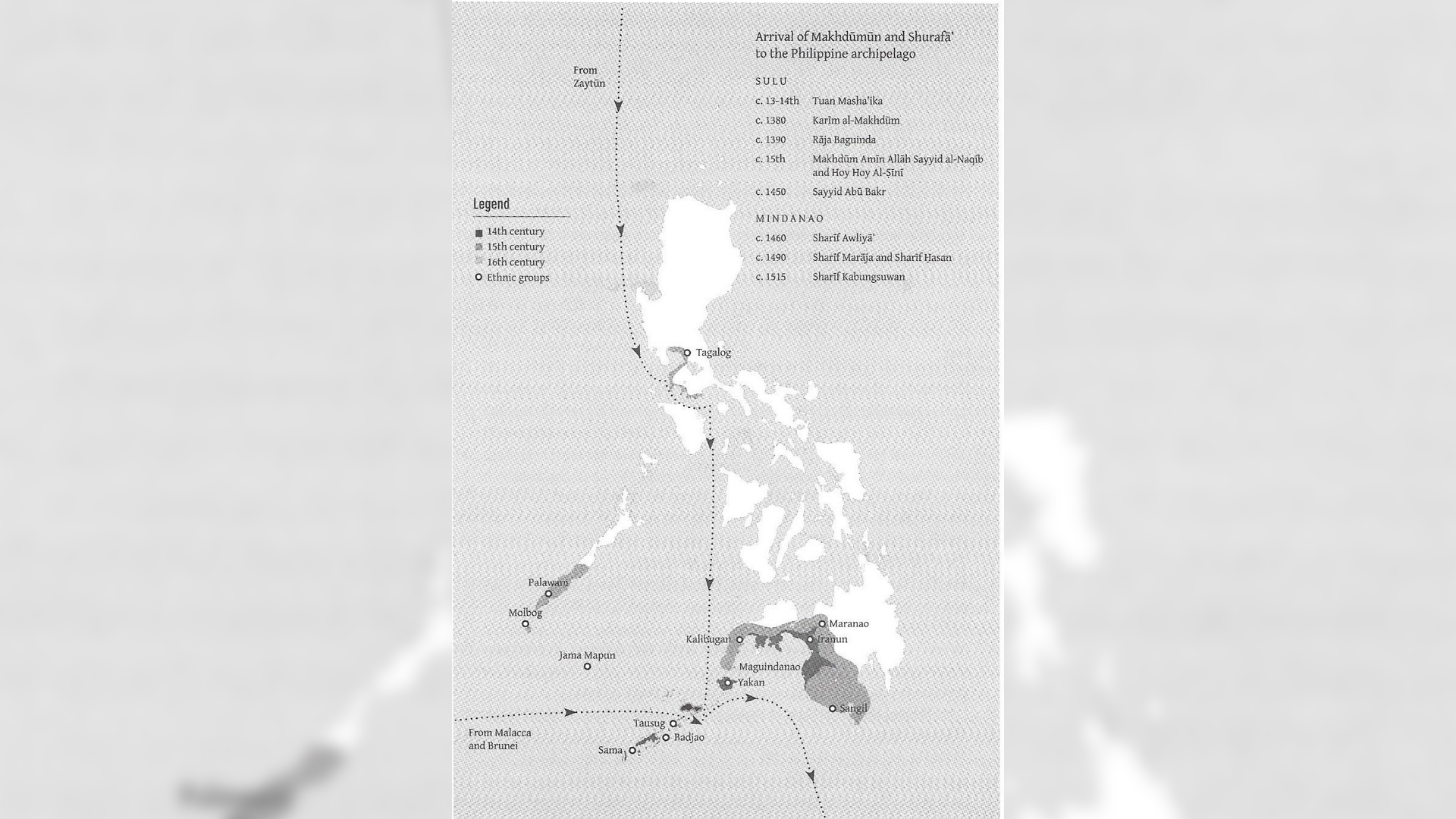

Arrival and Spread of Islam in the Sulu Archipelago 1270-1275

1270-1275

Arrival and Spread of Islam in the Sulu Archipelago 1270-1275

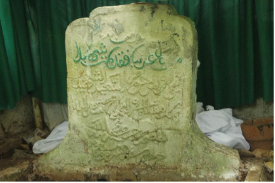

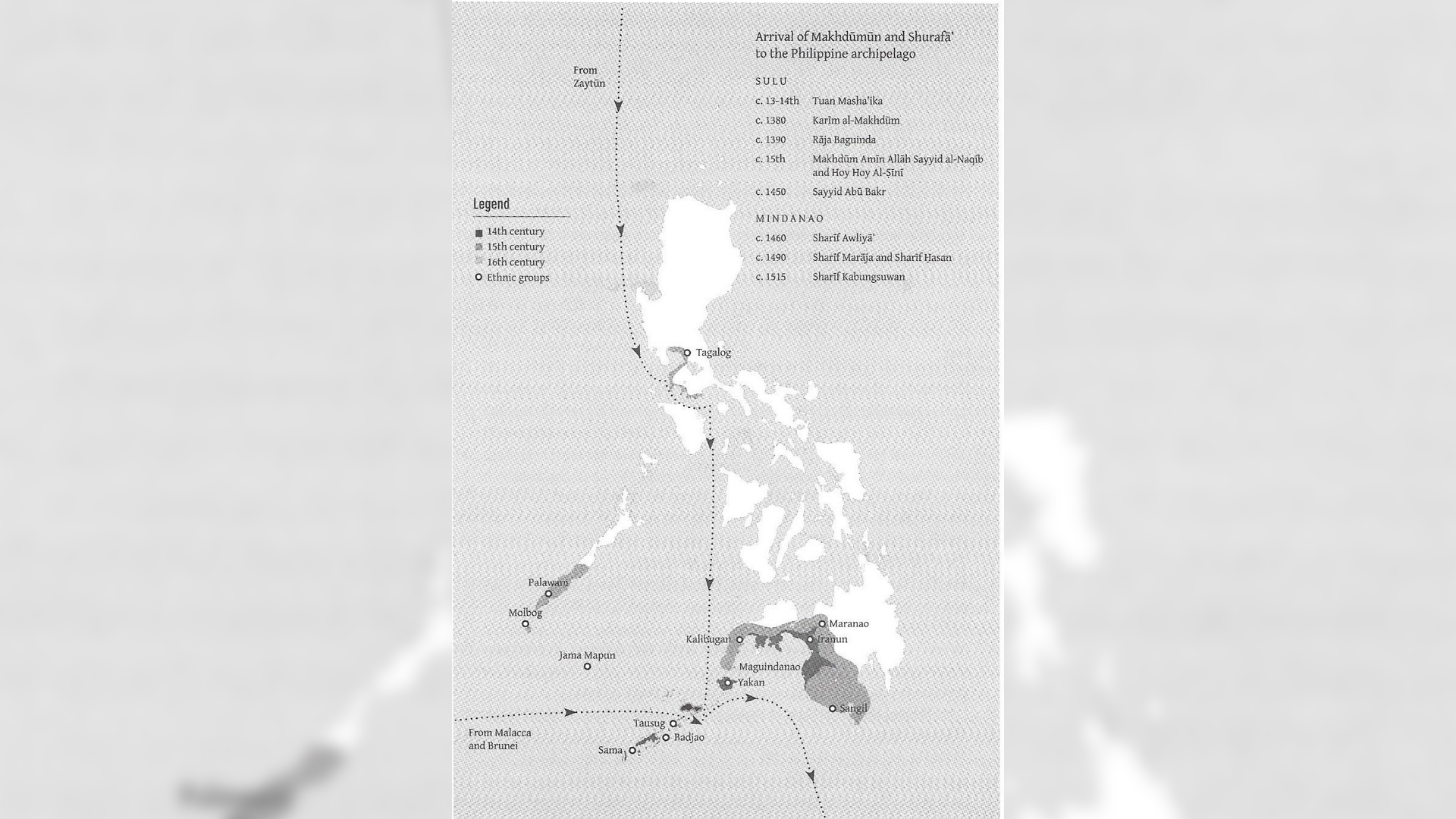

Entrance to the shrine of Ahmad Timhar Maqbalu in Bud Datu, Jolo, Sulu. Photo by Nickee Bultangan Tombstone Inscription of Ahmad Timhar Maqbalu in Bud Datu, Jolo, Sulu. Photo by Nickee Bultangan Description: The first preacher to have taught Islam in the Philippines was Ahmad Timhar Magbalu who came from Hadramaut in Yemen to Sulu around 1270-1275. More information: As early as 982 AD, foreign Muslims were already in the Philippines. Chinese account mentions of an Arab ship Mindoro who came to the port of Canton (Guangzhou). But the beginning of spread of Islam took place...

Description: The first preacher to have taught Islam in the Philippines was Ahmad Timhar Magbalu who came from Hadramaut in Yemen to Sulu around 1270-1275.

More information: As early as 982 AD, foreign Muslims were already in the Philippines. Chinese account mentions of an Arab ship Mindoro who came to the port of Canton (Guangzhou). But the beginning of spread of Islam took place in Sulu with the arrival of a Muslim preacher, Ahmad Timhar Maqbalu around 1270-75 AD. He is known in oral history as Tuan Mashaikha, a title indicating that he came from house of Mashā’ikh (learned) who were descendants of Prophet Muhammad through his grandson Husayn.

Because of his superior in knowledge, he acquired respect from the Tausug and married the daughter of the local chief. He died in 710 hijra/1310 leaving some descendants in Sulu. His missionary activity facilitated the slow transition from Hinduism or conversion to Islam of the local inhabitants. His shrine in Bud Datu serves as the oldest physical evidence of Islam in the country.

Sources:

Scott, Henry William. Filipinos in China before 1500. China Studies Program. Manila: De La Salle University, 1989.

Majul, Cesar A. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1999.

Al-Attas, Syed Muhammad Naguib. Historical Fact and Fiction. Malaysia: UTM Press, 2011.

Description: Karimul Makhdum was a celebrated Muslim Sufi preacher who first taught Islam among the Sama in Tawi-Tawi fifty years after the arrival of Tuan Mashaika in Sulu.

More information: Fifty years the death of Tuan Mashaikha, the celebrated Sufi preacher from Qadiri order, Ibrāhīm Zayn al-Dīn al-Akbar locally known as Karimul Makhdum (the Noble Master, landed with his men in Tawi-Tawi. He was the seventh generations from Imām Muhammad Sāhib Marbāt, the seventh generation from the Imām Ahmad bin ‘Īsā (d.961) surnamed the Emigrant (al-Muhājir) and the eighth generation from al-Husayn, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad. Karīmul Makhdum most of his life travelling to spread Islam. He taught Islam in East Java and was celebrated as the Sunan (revered person) of Nggesik (Tuban). Many Javanese saints descended from him. He travelled extensively in the Sulu archipelago to teach Islam.

Karimul Makhdum and his men must have arrived first in Sibutu island, South of Tawi-Tawi, built a mosque in Simunul and visited many islands of Sulu. He has been attributed with spiritual powers like walking on water.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar A. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1999.

Al-Attas, Syed Muhammad Naguib. Historical Fact and Fiction. Malaysia: UTM Press, 2011. Kurais II, Muhammad. The History of Tawi-Tawi and its People. Tawi-Tawi: Mindanao State University Sulu College of Technology and Oceanography, 1979.

Grave of Sultan Shariful Hashim in Mount Tumatangis, Jolo, Sulu. Photo by Darwin J. Absari

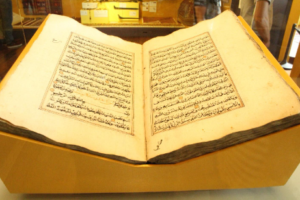

A digitalized manuscript by Princeton University of a book brought by Shariful Hashim to Sulu

Description: Sayyid Abukar, a Malay-Arab Prince came Basilan and later proceeded to Sulu to teach Islam and established the Sulu Sultanate in 1405.

More information: The culmination of the spread of Islam in Sulu was reached with the arrival of Sayyid Abubakar or locally known as Shariful Hashim. He belonged to the Bani Hāshim, the most noble line of Quraysh from which Prophet Muhammad was descended. He was the son of Sayyid ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin al-‘Alawi al-Husayni to a Malaccan Princess, daughter of Sultan Iskandar. His father, Sayyid ‘Ali Zayn al-‘Abidin was the fifth in line of descent from Sharif ‘Abd Allāh, son of Sharif ‘Alawī bin Muhammad Sāhib Marbāt from whom both Tuan Masha’ika and Karīmuk Makhdum descended from.

After studying Islam in Mecca, he came back to Malacca with a book Durr al-Manzum (The Strung Pearls) which he personally taught to the Malaccan Sultan who then ordered the book be translated to Malay.

He first stayed among the Yakan in Basilan. Later, he proceeded to Sulu upon the invitation of the Tausug. He arrived Sulu around 1395 and married the daughter of Raja Baginda, a prince from Menangkabaw who was the ruler of the coastal areas in Sulu. After the death of Raja Baguinda, Shariful Hashim consolidated the population, converted the remaining non-Muslims and established the Sulu sultanate in 1405 and became the first Sultan. He also built madrasa and organized the teaching of Qur’an and Hadith.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar A. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1999.

Al-Attas, Syed Muhammad Naguib. Historical Fact and Fiction. Malaysia: UTM Press, 2011.

Kurais II, Muhammad. The History of Tawi-Tawi and its People. Tawi-Tawi: Mindanao State University Sulu College of Technology and Oceanography, 1979.

Absari, Darwin J. PagTuhan: The Tausug Spiritual Tradition. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 2021.

Read More

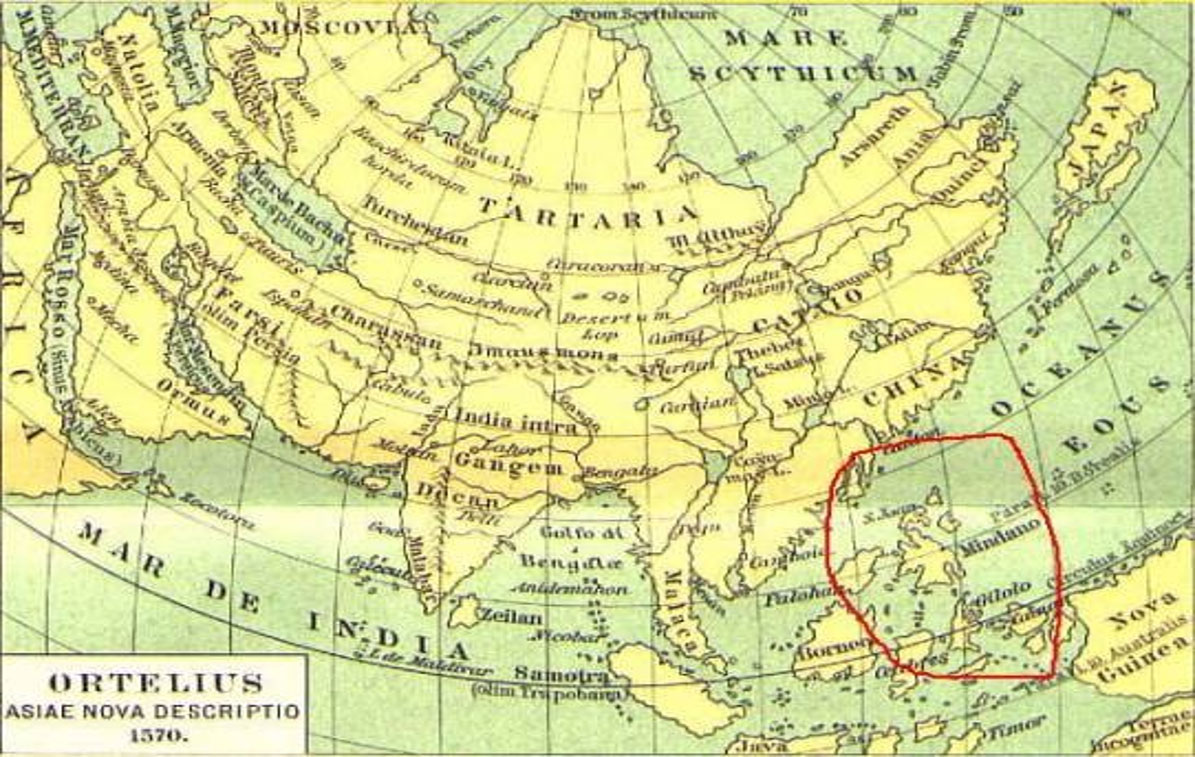

Map of Mindanao in Asia

AD 1370

Map of Mindanao in Asia, AD 1370 (Luzon and Visayas is not yet visible on this Map)

In traversing and up-streaming the saga of the Bangsamoro encounters against the Spanish colonial expansion in Mindanao and Sulu, as elsewhere in the Philippines, it is important to remember two common elements which provided Spanish pretext for intervention. The first was the natural consequence of the reconquista—pacification. This was often followed by a process of reduccion by which the Spanish missionaries sought to convert some of the native population into Christianity. The idea was to bring them under civil administration as well as under the Catholic Church. The conduct of Spain in dealing with the Magindanao (Maguindanao) and Sulu Sultans...In traversing and up-streaming the saga of the Bangsamoro encounters against the Spanish colonial expansion in Mindanao and Sulu, as elsewhere in the Philippines, it is important to remember two common elements which provided Spanish pretext for intervention. The first was the natural consequence of the reconquista—pacification. This was often followed by a process of reduccion by which the Spanish missionaries sought to convert some of the native population into Christianity. The idea was to bring them under civil administration as well as under the Catholic Church.

The conduct of Spain in dealing with the Magindanao (Maguindanao) and Sulu Sultans under treaty relations on the pretext of policy of attraction was actually part of the pacification strategy which is part of the topics in the succeeding slides. These treaties, were mostly defensive-offensive, alliance, political, commercial and military for these related to peaceful co-existence, commerce, armistice, and settlement of territorial disputes and delimitation of boundaries between Magindanaw (Maguindanao) and Filipinas, as well as commercial activities with Great Britain (Abdulhaq, 2011: p. 50).

Nua’ain Bin Abdulhaq (2011). Bangsamoro Dossier: Historical notes on the status of the Bangsamoro Homeland under Moro treaties with foreign powers. Agency of Youth Affairs-MILF.

Read More

Islam’s Further Spread to Maguindanao and Lanao Areas

1300

Islam’s Further Spread to Maguindanao and Lanao Areas

Grave of Sharif Awliya’s eldest son Sharif Shaikh Sagulandang in Tawan- Tawan, Maguindanao. Photo by Darwin Absari. Description: Karimul Makhdum proceeded to Mindanao to teach Islam among the Maguindanaon. He was the first Muslim missionary popularly called Sharif Awliya by the natives. More information: After teaching Islam in Sulu, Karimul Makhdum proceeded to Maguindanao via Zamboanga Peninsula. He arrived around 1365 and was known as Sharif Awliya since many of the saints in Java descended from him. He married the local princess and taught Islam before returning back to Java. He left a daughter named Paramisuli and three sons...

Grave of Sharif Awliya’s eldest son Sharif Shaikh Sagulandang in Tawan- Tawan, Maguindanao. Photo by Darwin Absari.

Description: Karimul Makhdum proceeded to Mindanao to teach Islam among the Maguindanaon. He was the first Muslim missionary popularly called Sharif Awliya by the natives.

More information: After teaching Islam in Sulu, Karimul Makhdum proceeded to Maguindanao via Zamboanga Peninsula. He arrived around 1365 and was known as Sharif Awliya since many of the saints in Java descended from him. He married the local princess and taught Islam before returning back to Java. He left a daughter named Paramisuli and three sons in Maguindanao.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar A. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1999.

Al-Attas, Syed Muhammad Naguib. Historical Fact and Fiction. Malaysia: UTM Press, 2011.

My interview with Sultan Sharif Kaharodin. February 28, 2006. Dulawan, Maguindanao.

The spread of Islam in Maguindanao culminated with the arrival of Sharif Kabungsuwan, who established the Maguindanao Sultanate in 1440. He is believed to be the younger brother of Sultan Shariful Hashim.

More Information:

Islam’s further spread in Maguindanao was accomplished by Sharif Muhammad Kabungsuwan, who was, accordingly, Shariful Hashim’s younger brother. He arrived in Maguindanao with his men and the seafaring people (Sama Dilaut) around 1440. He was met by the local chiefs Tabunaway and Mamalu, who were descendants of his uncle Sharif Maharaja.

Sharif Maharaja was another Muslim preacher who followed Sharif Awliya to Maguindanao to continue missionary work. His daughter was married to Sharif Maharaja, from whom Tabunaway and Mamalu descended. With the assistance of the two local chiefs, Sharif Kabungsuwan was able to consolidate the natives and establish the Sultanate of Maguindanao. He reigned for more than 20 years before returning home.

Sources:

Saleeby Najeeb M. 1905. Studies in Moro History, Law, and Religion. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

Majul, Cesar A. 1999. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Al-Attas, Syed Muhammad Naguib. 2011. Historical Fact and Fiction. Malaysia: UTM Press.

Sultan’s Palace or Grave of Sultan Sharif Kabunguwan in Indonesia/Malacca

The culmination of the spread of Islam in Maguindanao was reached with the arrival of Sharif Kabungsuwan who established the Maguindanao Sultanate in 1440. He is believed to be the younger brother of Sultan Shariful Hashim.

More Information:

Islam’s further spread in Maguindanao was accomplished by Sharif Muhammad Kabungsuwan who was accordingly Shariful Hashim’s younger brother. He arrived Maguindanao with his men and the seafaring people (Sama Dilaut) around 1440. He was met by the local chiefs Tabunaway and Mamalu who were descendants of his uncle Sharif Maharaja.

Sharif Maharaja was another Muslim preacher who followed Sharif Awliya to Maguindanao to continue his missionary works. His daughter was married to Sharif Maharaja from where Tabunaway and Mamalu descended. With the assistance of the two local chiefs, Sharif Kabungsuwan was able to consolidate the natives and established the Sultanate of Maguindanao. He reigned for more than 20 years before returning home.

Sources:

Saleeby Najeeb M. Studies in Moro History, Law, and Religion. Manila: Bureau of Printing, 1905.

Majul, Cesar A. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1999.

Al-Attas, Syed Muhammad Naguib. Historical Fact and Fiction. Malaysia: UTM Press, 2011.

The old Qur’an of Bayang, Lanao del Sur displayed at the National Museum in Manila. Photo by Darwin J. Absari

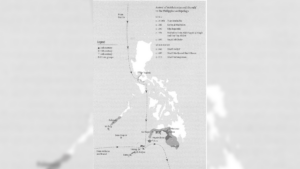

Description: Lanao areas were also Islamized by a certain Muslim preacher Sharif ‘Alawi and from the intermarriages between the Maguindanao rulers and Maranao datus.

More information: From Maguindanao, Islam slowly spread to some parts of Sarangani and Davao in the first half of the 17th century. With the same political and marriage alliances with the Maranao datus, Islam entered Lanao.

Local traditions also mention the coming of Sharif ‘Alawi who became chief of Misamis Oriental and whose preaching reached Lanao and Bukidnon. He is also believed to have left descendants in the area.

Source:

Majul, Cesar A. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1999.

Read More

Islam Moves North

1405

Islam Moves North

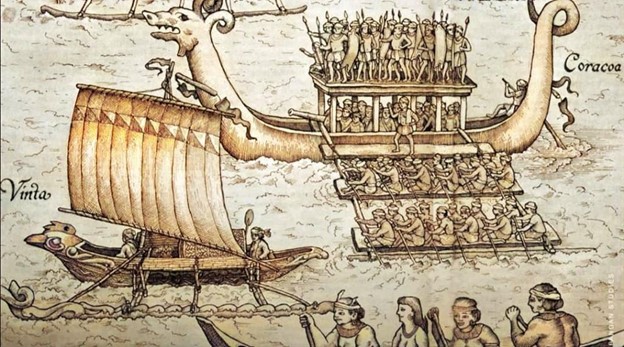

Introduction The flourishing interisland trade that has been taking place since the pre-Islamic era facilitated the further expansion of Islam to Visayas and Luzon by the people in Mindanao and Sulu who have now become Muslims. After the establishment of the Sulu Sultanate in 1405, Sulu’s power as a sovereign state was felt all over Luzon and the Visayas islands, Celebes Sea, Palawan, North Borneo, and the China Sea, and their trade extended from China and Japan, at the one extreme, and to Malacca, Sumatra, and Java at the other (Saleeby 1908). Some areas in the Philippines such as...

Introduction

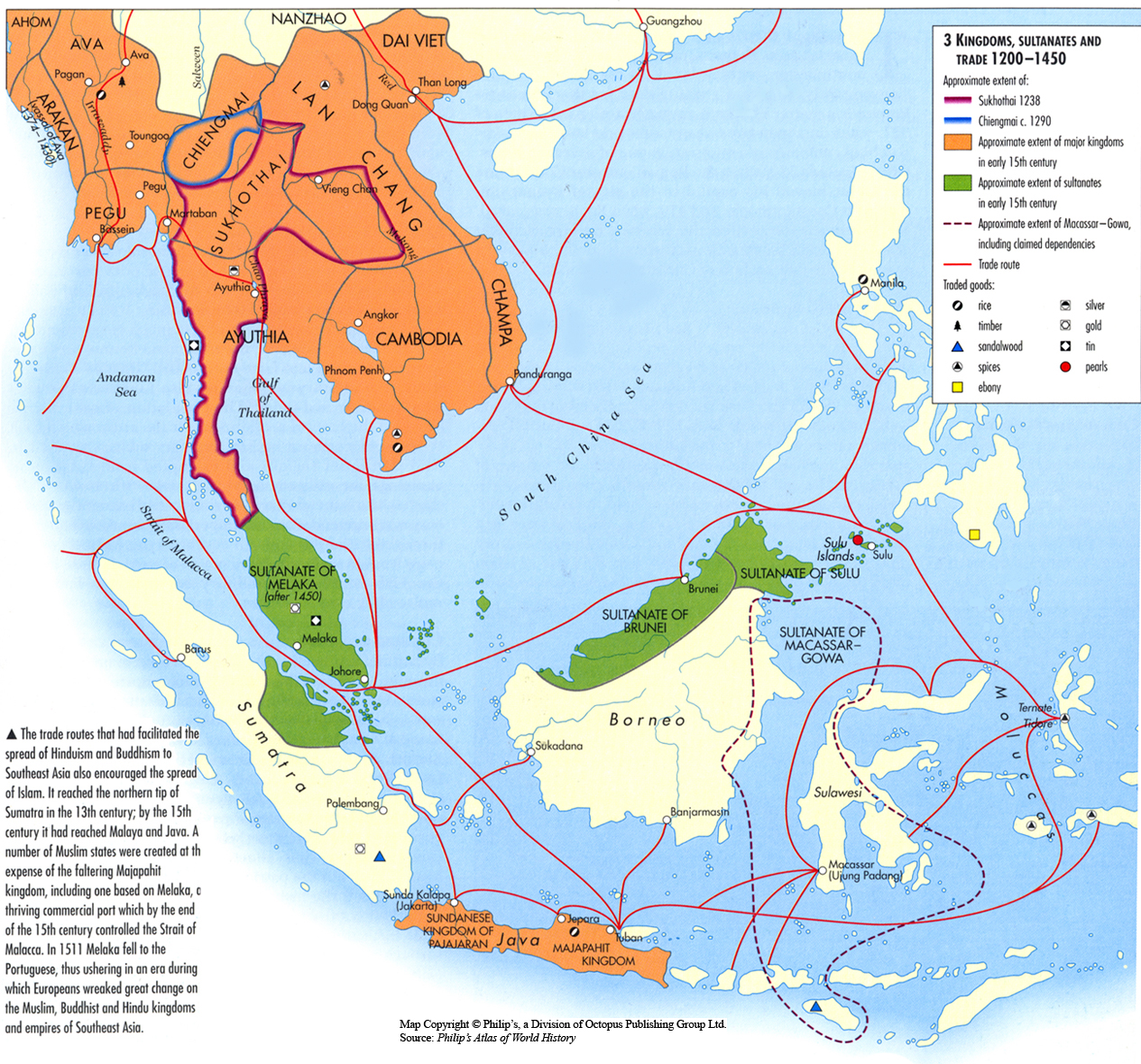

The flourishing interisland trade that has been taking place since the pre-Islamic era facilitated the further expansion of Islam to Visayas and Luzon by the people in Mindanao and Sulu who have now become Muslims.

After the establishment of the Sulu Sultanate in 1405, Sulu’s power as a sovereign state was felt all over Luzon and the Visayas islands, Celebes Sea, Palawan, North Borneo, and the China Sea, and their trade extended from China and Japan, at the one extreme, and to Malacca, Sumatra, and Java at the other (Saleeby 1908). Some areas in the Philippines such as Mindoro and Calamianes remained to be tributary states of the Sulu Sultanate until the coming of the Spaniards. (Majul 1999)

The Maguindanao Sultanate ruled over the whole southern coast of Mindanao from Point Tugubum, east of Mati, to Zamboanga, and beyond this latter point to the outskirts of Dapitan. All the non-Muslim tribes living around the Gulf of Davao and in the Sarangani country, and all the Subanons west of Tukurun and Dapitan submitted to its power and paid tribute to the sultanate. In the upper Rio Grande (Pulangi) Valley the power of the rajas of Bwayan was felt and respected as far as the watershed of the Cagayan Valley on the north and the inaccessible slopes of Mount Apo on the east. The M’ranaos controlled the whole of Lanao and the seacoast west of Cagayan de Misamis and north of the Illana Bay. During this period, traders as well as spiritual sages from Sulu and Mindanao visited the places of their trading partners in the country, and to some extent, were leading in the interisland as well as the overseas trade of their non-Muslim brethren.

Sources:

Majul, Cesar A. 1999. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Saleeby, Najeeb M. 1905. Studies in Moro History, Law, and Religion. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing,.

According to Chinese sources, the earliest presence of Muslims in the country was in 982 AD in Mindoro. However, the beginning of Islam’s spread to Luzon and the Visayas took place at the height of the Sulu Sultanate and was reinforced by Bornean preachers in the sixteenth century.

More information:

Islam was present in Luzon as early as 982 AD. A Chinese document mentions an Arab ship from Mindoro that went to China. However, the initial spread of Islam to the Visayas and Luzon took place at the height of the Sulu Sultanate at the beginning of the fifteenth Century. Some areas in Luzon and the Visayas were under the influence of the Sulu Sultanate.

This initial spread was later reinforced when the Brunei sultan took over Manila and brought in Muslim missionaries who reached as far as Batangas, Cebu, Mindoro, Oton in Iloilo, and Bonbon in Butuan. Spanish Historian Antonio Morga wrote, “If the entrance of the Spaniards had been longer delayed, this sect would have extended all over the island, and even throughout the others; and it would have been difficult to have uprooted it from them.”

However, the slow spread of Islam to Luzon and the Visayas was halted with the arrival of Spaniards in the mid-sixteenth century. But legacies of Islam continue to survive in the language, psychology, and way of life of the Christianized natives.

Sources:

Donoso, Isaac. 2013. Islamic Fareast: Ethnogenesis of Philippine Islam. University of the Philippines Press.

Majul, Cesar A. 1999. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Read More

Legacy of Islam in Luzon and the Visayas

1450

Legacy of Islam in Luzon and the Visayas

Islamic legacies can be seen even in the architectural design of churches built by the Spaniards especially in Cebu and Bohol. More Information: The long Spanish evangelization in Luzon and the Visayas did not entirely erase Islam’s legacies among the Christianized natives. These legacies came via the Tausug of Sulu, Malay, and even the Spaniards. Kapwa (fellow human being), according to the Filipino indigenous concept, is a shared identity. The unity of the self and others reflects the Islamic concept of Tawhid that Filipino Muslims apply in their interpersonal relationships. Henry William Scott’s Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of...Islamic legacies can be seen even in the architectural design of churches built by the Spaniards especially in Cebu and Bohol.

More Information:

The long Spanish evangelization in Luzon and the Visayas did not entirely erase Islam’s legacies among the Christianized natives. These legacies came via the Tausug of Sulu, Malay, and even the Spaniards. Kapwa (fellow human being), according to the Filipino indigenous concept, is a shared identity. The unity of the self and others reflects the Islamic concept of Tawhid that Filipino Muslims apply in their interpersonal relationships.

Henry William Scott’s Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History (1984) and John Wolff’s Malay Borrowings in Tagalog (1976) reveal some relevant Tagalog words borrowed from Malay and Arabic. One of the most important words is simbahan (house of worship or church), derived from the root word simba (worship). Simba, as revealed by the works of Scott and Wolff, is derived from the Malay word sumba (worship), which originally came from the Arabic term subha (praise).

Interesting to note that the old simbahan (churches) in the Philippines, especially those in Cebu and Bohol, also reveal Islamic influence, particularly from mosques in Spain. Spaniards brought with them their Islamic roots, as the Moors had Islamized them for nearly 800 years. Alicia Coseteng, in her Spanish Churches in the Philippines (1972), wrote:

Muslim influence is much more pervasive in the southern

regions, especially in Bohol and Cebu. Churches in these regions

carry elements and motifs which are reminiscent of the Mudejar

in Spain and Mexico. Minaret-like bell towers with their onion-shaped

domes or four-cornered hat roofs, like those of the

Church in Carcar, and the highly stylized design of the façade

of the church in Naga, Cebu, indicates strong Muslim influence.

Floral and geometric patterns—delicate, flat, stylized—on the

facades and in the interior of churches in these two provinces

reveal distinctly Moorish origins. Lattice work, inlays, carved

woodwork, blind balustrades, trilobular and ogee arches, spiral

columns, all these are charming evidence of Muslim art on

colonial religious architecture.

Even some Spanish loan words in Tagalog originated from Arabic, such as alcalde (mayor) from the Arabic term al-Qadi (judge), barrio/baryo (district) from barrī (less urbanized parts of the city), and many others.

Sources:

Scott, Henry William. 1984. PreHispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History(Revised Edition). Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Donoso, Isaac. ed. 2018. More Islamic Than We Admit. Insights into Philippine Cultural History. Quezon City: Vival Foundation, Inc.

Absari, Darwin J. 2021. PagTuhan: The Tausug Spiritual Tradition. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Coseteng, Alicia M. L. 1972. Spanish Churches in the Philippines. New Mercury Printing Press, Quezon City, Philippines.

Summary:

The arrival of various eastern civilizations (Indian, Chinese, and Islam) to Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago via sea trade before the advent of western colonial invaders nurtured the growth of the Bangsamoro civilization. The Indians, Chinese, and Muslims who came to trade with the natives of Mindanao and Sulu brought with them their culture and religious traditions that exposed the native inhabitants to a universalistic religion with a sophisticated intellectual tradition. This confluence of tradition was achieved due to the tolerance of these Indians, Chinese, and Muslims who did not attempt to conquer the native, and the natives’ openness to receiving people of different religions. Each eastern civilization left a legacy harmoniously integrated in the culture, language, and religious tradition of the people of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago. Islam being the last carrier of eastern civilization has brought Mindanao and Sulu civilization to its peak when Muslim preachers established the sultanates whose power and dominion did not only reach almost the entire country but also neighboring Southeast Asian countries.

By the mid-sixteenth century, the Muslims’ power and prosperity began to be challenged by Western colonizers, first by the Spaniards and later the Americans whose agenda was to control and monopolize the rich economic activities under the guise of religious evangelization and democratization. For more than three hundred years, the Muslims resisted the protracted war that has affected their political, economic, and religious life.

Read More

The Papal Bull of 1493

The Papal Bull of 1493 issued by Pope Alexander VI was a document that authorized the Spanish government to colonize, enslave and spread Catholicism using force if necessary. It was here when the Philippines was subjugated and brought under Spanish Crown, while the Muslims in the south fought to remain free.

The Papal Bull of 1493

Excerpt from the English Translation of the 1493 Papal Bull Wherefore, as becomes Catholic kings and princes, after earnest consideration of all matters, especially of the rise and spread of the Catholic faith, as was the fashion of your ancestors, kings of renowned memory, you have purposed with the favor of divine clemency to bring under your sway the said mainlands and islands with their residents and inhabitants and to bring them to the Catholic faith. Hence, heartily commending in the Lord this your holy and praiseworthy purpose, and desirous that it be duly accomplished, and that the name of...Excerpt from the English Translation of the 1493 Papal Bull

Wherefore, as becomes Catholic kings and princes, after earnest consideration of all matters, especially of the rise and spread of the Catholic faith, as was the fashion of your ancestors, kings of renowned memory, you have purposed with the favor of divine clemency to bring under your sway the said mainlands and islands with their residents and inhabitants and to bring them to the Catholic faith. Hence, heartily commending in the Lord this your holy and praiseworthy purpose, and desirous that it be duly accomplished, and that the name of our Savior be carried into those regions, we exhort you very earnestly in the Lord and by your reception of holy baptism, whereby you are bound to our apostolic commands, and by the bowels of the mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ, enjoy strictly, that inasmuch as with eager zeal for the true faith you design to equip and despatch this expedition, you purpose also, as is your duty, to lead the peoples dwelling in those islands and countries to embrace the Christian religion; nor at any time let dangers or hardships deter you therefrom, with the stout hope and trust in your hearts that Almighty God will further your undertakings. And, in order that you may enter upon so great an undertaking with greater readiness and heartiness endowed with benefit of our apostolic favor, we, of our own accord, not at your instance nor the request of anyone else in your regard, but out of our own sole largess and certain knowledge and out of the fullness of our apostolic power, by the authority of Almighty God conferred upon us in blessed Peter and of the vicarship of Jesus Christ, which we hold on earth, do by tenor of these presents, should any of said islands have been found by your envoys and captains, give, grant, and assign to you and your heirs and successors, kings of Castile and Leon, forever, together with all their dominions, cities, camps, places, and villages, and all rights, jurisdictions, and appurtenances, all islands and mainlands found and to be found, discovered and to be discovered towards the west and south, by drawing and establishing a line from the Arctic pole, namely the north, to the Antarctic pole, namely the south, no matter whether the said mainlands and islands are found and to be found in the direction of India or towards any other quarter, the said line to be distant one hundred leagues towards the west and south from any of the islands commonly known as the Azores and Cape Verde. With this proviso however that none of the islands and mainlands, found and to be found, discovered and to be discovered, beyond that said line towards the west and south, be in the actual possession of any Christian king or prince up to the birthday of our Lord Jesus Christ just past from which the present year one thousand four hundred ninety-three begins. And we make, appoint, and depute you and your said heirs and successors lords of them with full and free power, authority, and jurisdiction of every kind; with this proviso however, that by this our gift, grant, and assignment no right acquired by any Christian prince, who may be in actual possession of said islands and mainlands prior to the said birthday of our Lord Jesus Christ, is hereby to be understood to be withdrawn or taking away. Moreover we command you in virtue of holy obedience that, employing all due diligence in the premises, as you also promise—nor do we doubt your compliance therein in accordance with your loyalty and royal greatness of spirit—you should appoint to the aforesaid mainlands and islands worthy, God-fearing, learned, skilled, and experienced men, in order to instruct the aforesaid inhabitants and residents in the Catholic faith and train them in good morals. Furthermore, under penalty of excommunication “late sententie” to be incurred “ipso facto,” should anyone thus contravene, we strictly forbid all persons of whatsoever rank, even imperial and royal, or of whatsoever estate, degree, order, or condition, to dare without your special permit or that of your aforesaid heirs and successors, to go for the purpose of trade or any other reason to the islands or mainlands, found and to be found, discovered and to be discovered, towards the west and south, by drawing and establishing a line from the Arctic pole to the Antarctic pole, no matter whether the mainlands and islands, found and to be found, lie in the direction of India or toward any other quarter whatsoever, the said line to be distant one hundred leagues towards the west and south, as is aforesaid, from any of the islands commonly known as the Azores and Cape Verde; apostolic constitutions and ordinances and other decrees whatsoever to the contrary notwithstanding. We trust in Him from whom empires and governments and all good things proceed, that, should you, with the Lord’s guidance, pursue this holy and praiseworthy undertaking, in a short while your hardships and endeavors will attain the most felicitous result, to the happiness and glory of all Christendom.

Source: https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/doctrine-discovery-1493

Read More

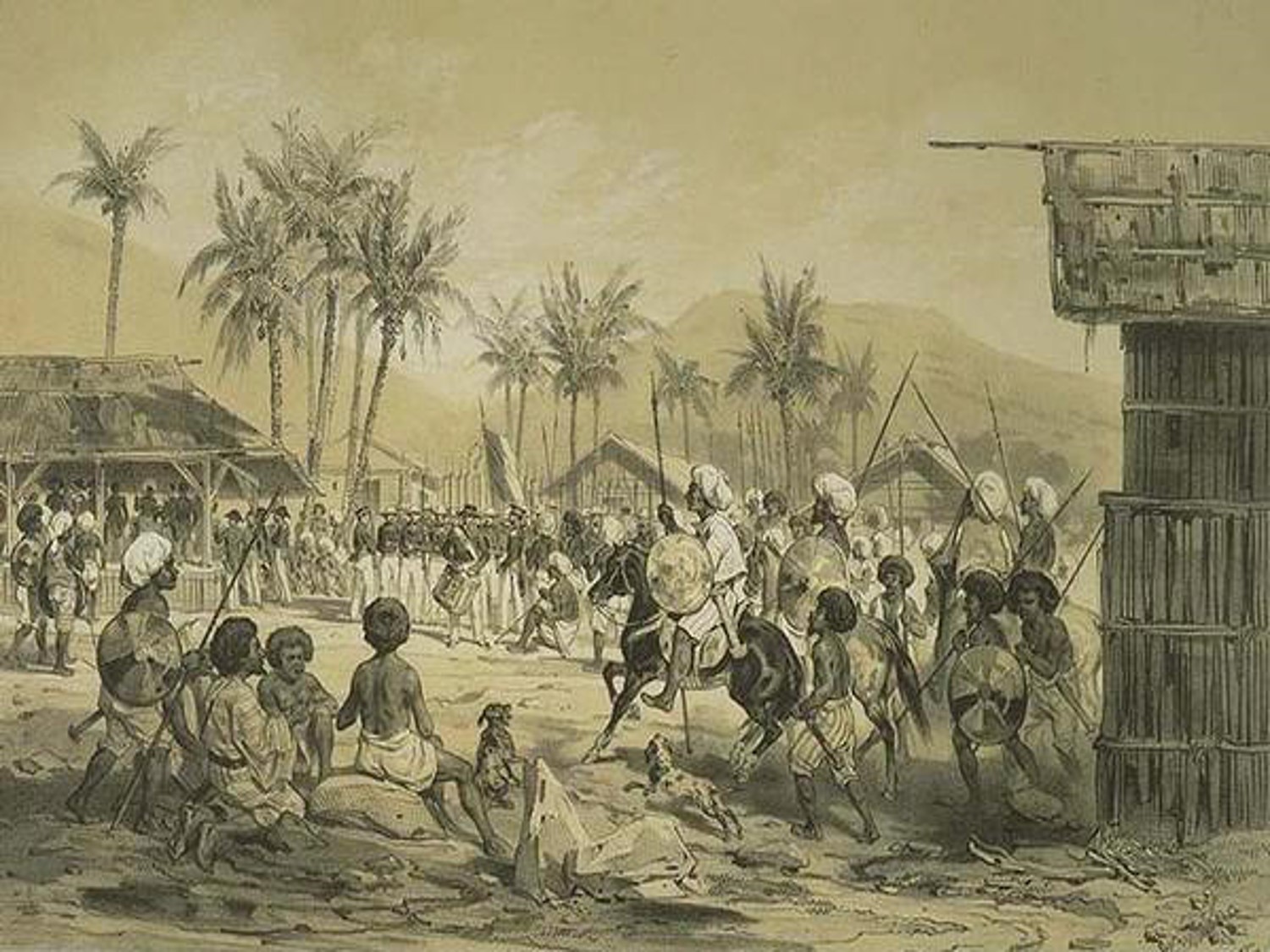

First military victory of Buayan’n in Sarangani against the Villalobos Expedition of imperial Spain

1543

Rajah Silongan military defense system is well organized based on the standard of the era. The first recorded military defeat suffered by the Spanish colonizer against Buwayan people (Buwayan’n) was happened in 1543. Headed by Captain Bernardo de la Torre of the Villalobos Expedition, the Captain with his 200 men landed in Sarangani Island (Sugod a Buwayan). “Disheartened by the hostility of the Buwayan people in Sarangani Bay and haunted by the shortage of provisions due to food blockade, the Villalobos Expedition was forced to withdraw and sailed to the Moluccas” (see: Carta Escrita por Fray Geronimo de Santisteban. Also...Rajah Silongan military defense system is well organized based on the standard of the era. The first recorded military defeat suffered by the Spanish colonizer against Buwayan people (Buwayan’n) was happened in 1543. Headed by Captain Bernardo de la Torre of the Villalobos Expedition, the Captain with his 200 men landed in Sarangani Island (Sugod a Buwayan). “Disheartened by the hostility of the Buwayan people in Sarangani Bay and haunted by the shortage of provisions due to food blockade, the Villalobos Expedition was forced to withdraw and sailed to the Moluccas” (see: Carta Escrita por Fray Geronimo de Santisteban. Also in Zaide, 1949. The Philippine Since Pre-Spanish Time). Like Loaisa and Saavedra Expeditions, Villalobos failed to colonize, the now Philippine Islands. But this time, the successful defense was entirely credited to the military mettle of Buwayan.

“For good sources on the expedition of Villalobos, see Fr. Geronimo de San Esteban, “Carta escrita for Fray Geronimo de Santisteban a Don Antonio Mendoza, Virey de Nueva Espana, relacionando la perida de la Armada que salio en 1543, para las Islas Poniente, al cargo de Ruy Lopez de Villalobos. Cochin, India de Portugar, 22 de Enero, 1547.”

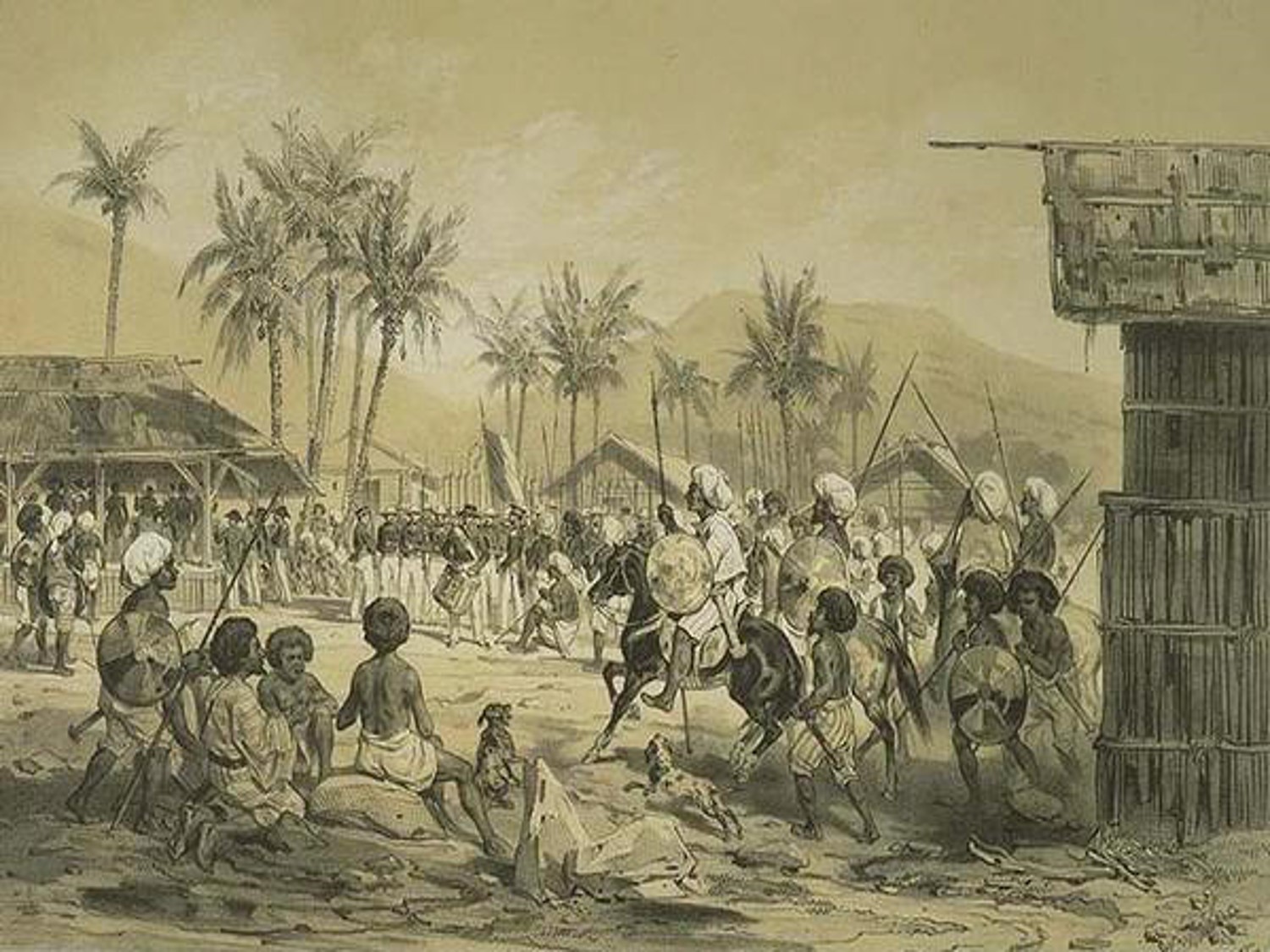

The Battle of Bangkusay between the young Macabebe Chief Tariq Sulayman and Miguel Lopez de Legazpi in June 1572. (by Dan H. Dizon in Center for Kampampangan Studies, Holy Angel University. Photo was provided by Ian Alfonso)

June 1572

The Fall of Islamic Manila to Legazpi and the Birth of Moro Identity

Spanish’s attempt to colonize Manila was met with fierce resistance by Muslim leaders: Raja Sulayman in May 1570 and Tariq Sulayman from Pampanga in June 1571 whom the Spaniards called Moros. But with the help of Christianized natives from Visayas, both resistances fell, and Catholicism rapidly spread to almost entire Luzon and Visayas areas. More Information: The first Spanish expedition sent to the Fareast was led by a Portuguese, Ferdinand Magellan who arrived Visayas area in 1521. Although he successfully converted the natives to Catholicism, he was killed in Mactan by Lapu Lapu’s men who were believed to be Muslims....Spanish’s attempt to colonize Manila was met with fierce resistance by Muslim leaders: Raja Sulayman in May 1570 and Tariq Sulayman from Pampanga in June 1571 whom the Spaniards called Moros. But with the help of Christianized natives from Visayas, both resistances fell, and Catholicism rapidly spread to almost entire Luzon and Visayas areas.

More Information: The first Spanish expedition sent to the Fareast was led by a Portuguese, Ferdinand Magellan who arrived Visayas area in 1521. Although he successfully converted the natives to Catholicism, he was killed in Mactan by Lapu Lapu’s men who were believed to be Muslims.

After Magellan, King Charles sent three more expeditions; in 1525, 1526 and 1527 but all ended in failure. Frustrated and bankrupt, he agreed to sign the Treaty of Zaragosa with Portugal in 1529 which defined the areas of influence of both countries in Asia. A demarcation line at 297.5 leagues east of the Moluccas was drawn. All lands west of the line including Moluccas and Philippines belonged to Portugal. To east were for Spain.

Despite of the treaty, in 1542, King Charles I sent an expedition headed by Lopez de Villalobos to establish a permanent settlement in the Philippines. After a year, the expedition arrived in the island of Sarangani, south of Mindanao. But hunger and stiff hostilities of the Moros forced Villalobos to abandon the expedition. On their way to Moluccas where they were imprisoned by the Portuguese, they passed by Samar-Leyte. Bernard de la Torre, one of the crews, named the island Las Islas Filipinas or the Philippine Islands in honor of the Spanish Crowned, Prince Philip II. The name was later applied to the entire archipelago and was anglicized by the Americans to its present name, Philippines (Jubair, 1999).

In 1556, Philip II ascended to the throne and made it an official policy to colonize the Philippines. On April 27, 1565, Spanish expedition under Miguel Lopez de Legazpi arrived in Panay. In five years, Legazpi have subjugated Panay and areas near Cebu, and destroyed Muslim fortified outpost in Mindoro. Bearing the hatred against their Muslim enemies in Spain and the same people who stood as the main obstacle to their economic ambition in the Philippines, King Phillip II affirmed this policy in his written instruction to Miguel Lopez de Legazpi in 1566, which partly reads, “We give you permission to make such Moros slaves and to seize their property.” After acquiring the help of Visayan natives, Legazpi sent Martin de Goiti with 120 Spanish soldiers and hundreds of Visayan natives in early May of 1570 to deal with Raja Sulayman in Manila.

After the siege of Manila, Goiti returned to Panay with some booties. A year later, on May 03, 1571, Spaniards led by Legazpi himself, with 250 harquebusiers and 600 Visayan natives, returned to finally take Manila permanently for their economic ambition in the country. But another organized resistance was launched by a young Macabebe chief from Pampanga, Tariq Sulayman. His death however led to the defeat of his entire 2,000 warriors against 80 Spaniards and some 500 native Visayan allies.

With the defeat of Raja Sulayman and the young Macabebe chief, all resistance to Spanish rule in Luzon and Visayas including the aborted Magat Salamat Conspiracy in Tondo in 1578 were suppressed by the Spaniards. In a span of eleven years, almost the entire Luzon and Visayas were reduced into vassalage to Spanish crown and subjected to Spanish control. But the Moros in Sulu and Mindanao remain free, and the Spaniards will have yet to deal with them.

Sources:

Jubair, Salah. Bangsamoro: A Nation Under Endless Tyranny. Kuala Lumpur: IQ Marin, 1999.

Alfonso, Ian Christopher B. The Nameless Hero. Pampanga: Holy Angels University Press, 2016.

Majul, Cesar A. The Muslims in the Philippines. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1999.

Wadi, Julkipli M. Rajah Sulayman, Spain and the transformation of the Islamic Manila. Quezon City: RAIS Publication, 2009.

Read More

Governor Francisco de Sande sent invasion troops in Brunei in and in Jolo and Magindanaw (Maguindanao), all but doomed into oblivion except for Brunei were de Sande occupied the Sultanate for a few months only after his Spanish and Indio (later Filipino) colonial troops were decimated by an herb-borne plague.

1578

Governor Francisco de Sande sent invasion troops in Brunei in and in Jolo and Magindanaw (Maguindanao), all but doomed into oblivion except for Brunei were de Sande occupied the Sultanate for a few months only after his Spanish and Indio (later Filipino) colonial troops were decimated by an herb-borne plague. The Spaniard’s seizure of Paduka Sri Sultan Saiful Rijal Nurul ‘Alam’s Fort, Kota Batu, at the city of Brunei Darussalam during the Brunei-Spanish War of April 1578 wherein the famous Istana and Jami’ Brunei of Sultan Saiful Rijal were ransacked of its belongings by Governor Francisco de Sande which included...Governor Francisco de Sande sent invasion troops in Brunei in and in Jolo and Magindanaw (Maguindanao), all but doomed into oblivion except for Brunei were de Sande occupied the Sultanate for a few months only after his Spanish and Indio (later Filipino) colonial troops were decimated by an herb-borne plague.

The Spaniard’s seizure of Paduka Sri Sultan Saiful Rijal Nurul ‘Alam’s Fort, Kota Batu, at the city of Brunei Darussalam during the Brunei-Spanish War of April 1578 wherein the famous Istana and Jami’ Brunei of Sultan Saiful Rijal were ransacked of its belongings by Governor Francisco de Sande which included a large beautiful mimbar, a block of marble, and through which the Bruneians claimed contained water wherein whoever bathed went stright to heaven at his death. It was said that the famous Jami’ Brunei was a world-famous architectural wonder of the age (Cited in http://www.4wnet/royalark/Brunei/brunei4.htm.).

Emma, Blair and Robertsons. The Philippine Islands. Vol 17, p. 286.

Read More

MAY 23, 1578

Governor Francisco de Sande gave instructions to Captain Estevan Roriguez de Figueroa to conquer the Moros, as follows: Conquer the Moros of the Sultanate of Sulu and reduce them to Spanish vassalage and exact tribute from them; Let the Moros trade with the Spaniards as far as Manila and the present day Brunei Darussalam; Recover the two galleys, three small vessels, artilleries and ammunition seized by the Sulu Moros from the Spaniards; Find out the artilleries and anchors of a Spanish ship lost in Sulu waters in 1575; Prevent the Moros from attacking the Spanish held territories in the Pintados...Governor Francisco de Sande gave instructions to Captain Estevan Roriguez de Figueroa to conquer the Moros, as follows:

- Conquer the Moros of the Sultanate of Sulu and reduce them to Spanish vassalage and exact tribute from them;

- Let the Moros trade with the Spaniards as far as Manila and the present day Brunei Darussalam;

- Recover the two galleys, three small vessels, artilleries and ammunition seized by the Sulu Moros from the Spaniards;

- Find out the artilleries and anchors of a Spanish ship lost in Sulu waters in 1575;

- Prevent the Moros from attacking the Spanish held territories in the Pintados Island, i.e. Visayas and Luzon by commanding the Moros to stay on land, sow, cultivate and develop the pearl industry for Spanish commercial purposes;

Emma, Blair and Robertsons. “Expedition to Borneo, Jolo and Mindanao, Vol. 3, pp. 105- 107.

6. Put an end to Moro attacks against Spanish vessels;

- Put an end to the preaching of Islam especially those missionaries coming from Brunei Darussalam because, in the words of de Sande, the doctrine of Mahoma is evil and false, and that the Christian alone is good”, burn and destroy the homes of the Islamic missionaries and see to it these are not rebuilt;

- Convert the Sultan of Magindanaw and his people to Christianity;

- Destroy the Moros and their generations in retaliation for the killing of Villalobos and his men on February 8, 1546 by the Portuguese in Ambon (part of Indonesia); and

- Conquer the Moros everywhere, exact tribute from them, and divide their lands into encomiendas for Figueroa’s soldier.

Gregorio F Zaide and Sonia M. Zaide. Documentary Sources of Philippine History. Manila: National Book Store, 1990 (12 volumes).

Read More1578-1596 Second Stage of the Moro War

1578-1596

Second Stage of the Moro War

The 2nd Stage of the Moro Wars covering about two decades (1578-1596), was marked by Spanish attempts at establishing a colony in Mindanao, reducing a the Muslim rulers there and in Sulu to vassalage, and expelling the foreign preachers of Islam while encouraging the introduction of Christian missionaries. In 1596, the designated Spanish governor for Mindanao, Captain Esteban Rodriguez de Figueroa was slain by Maguindana Moro named Datu Mangubal (a.k.a.Ubal). It is significant that in this stage the Sultan of Ternate came to aid of the Sultan of Mindanao against the Spaniards (Gowing, 1979: p. 32). Gowing, Peter G. (1979)....The 2nd Stage of the Moro Wars covering about two decades (1578-1596), was marked by Spanish attempts at establishing a colony in Mindanao, reducing a the Muslim rulers there and in Sulu to vassalage, and expelling the foreign preachers of Islam while encouraging the introduction of Christian missionaries. In 1596, the designated Spanish governor for Mindanao, Captain Esteban Rodriguez de Figueroa was slain by Maguindana Moro named Datu Mangubal (a.k.a.Ubal). It is significant that in this stage the Sultan of Ternate came to aid of the Sultan of Mindanao against the Spaniards

(Gowing, 1979: p. 32).

Gowing, Peter G. (1979). Muslim Filipinos – Heritage and Horizon. Quezon City: New Day Publisher.

Expedition headed by Captain Gabriel de Ribera

1579

Expedition headed by Captain Gabriel de Ribera

An expedition headed by Captain Gabriel de Ribera was sent by Governor Francisco de Sande to Mindanao and Jolo, to secure Moro submission to Spanish authority. He went to Rio Grande de Mindanao but failed to conquer the place due to the strong military defense of the Confederacy of Magindanao, Tamontaka and Bwayan under the leadership of Rajah Buayan Silongan (see Ileto, 1971). According to Montero y Vidal (1888), the Rajah of Buayan (Sultan de Buhayen) is demonstrating a fierce military characteristic with strong military command. Ileto, Reynaldo C. 1971. Maguindanao, 1860-1888: The Career of Dato Utto of Buayan. Data...An expedition headed by Captain Gabriel de Ribera was sent by Governor Francisco de Sande to Mindanao and Jolo, to secure Moro submission to Spanish authority. He went to Rio Grande de Mindanao but failed to conquer the place due to the strong military defense of the Confederacy of Magindanao, Tamontaka and Bwayan under the leadership of Rajah Buayan Silongan (see Ileto, 1971). According to Montero y Vidal (1888), the Rajah of Buayan (Sultan de Buhayen) is demonstrating a fierce military characteristic with strong military command.

Ileto, Reynaldo C. 1971. Maguindanao, 1860-1888: The Career of Dato Utto of Buayan. Data Paper No. 32. Cornell University.Montero, Jose Y. Vidal. 1888. Historia de la Pirateria Malayo-Mohametana en Mindanao,jolo y Borneo (Tomo II). Madrid Imprenta y Fundicion de Manuel Tello.

Read MoreInvasion of the Rajahnate (Kerajaan) of Bwayan

April 25, 1596

Invasion of the Rajahnate (Kerajaan) of Bwayan

The Spanish government gave Captain Rodriguez de Figueroa the sole right to colonize Mindanao. On April 1, 1596 Figueroa left for Mindanao with the force of 50 war vessels, 214 Spaniards and 1,500 native allies (Indios). On April 25, 1596, after three (3) weeks of sea voyage, the fleet reached the mouth of the Pulangi or what the Spaniards called Rio Grande de Mindanao and started cruising upstream which was tough and exhausting. The river current was swift. They landed in Tampakan and immediately Figueroa lined up his troops in battle array and delivered the following stirring speech: “Soldiers of...The Spanish government gave Captain Rodriguez de Figueroa the sole right to colonize Mindanao. On April 1, 1596 Figueroa left for Mindanao with the force of 50 war vessels, 214 Spaniards and 1,500 native allies (Indios). On April 25, 1596, after three (3) weeks of sea voyage, the fleet reached the mouth of the Pulangi or what the Spaniards called Rio Grande de Mindanao and started cruising upstream which was tough and exhausting. The river current was swift. They landed in Tampakan and immediately Figueroa lined up his troops in battle array and delivered the following stirring speech:

“Soldiers of Felipe! We stand upon the newest soil of Spain. To subdue this dark forest and rid the soil of the infidel Moslem is our aim. They submit as vassals and converts or fall before Spanish blades. Forward to our duty for King and country.” (Hurley, 1936)

On the same date, Figueroa met with crushing defeat in Bwayan and was killed in an ambush by a Rajah Buwayan warriors (Buhahayen) named Datu Mangubal a.k.a. “Datu Ubal” in their fierce battle at Da-ubab (now Barangays Semba, Capiton in Datu Odin Sinsuat, Maguindanao del Norte; and part of Barangay Tamontaka Mother in Cotabato City). His forces retreated to La Caldera, at the southern tip of the Zamboanga peninsula, leaving the prestige of Buayan intact. Anticipating a second invasion, Rajah Sirongan and the other Buayans sent Datu Buisan to Ternate to ask for help. Morga (1609), has the following narration:

. . . whereupon the King of Ternate sent Mindanao a fleet of many caracoas or rowing-barges and other vessels commanded by cachils with selected soldiers numbering over one thousand (1,000) warriors and a number of light artillery pieces with which to compel the Spaniards to break their camp near the mouth of the Pulangi and go away. . . (p.57).

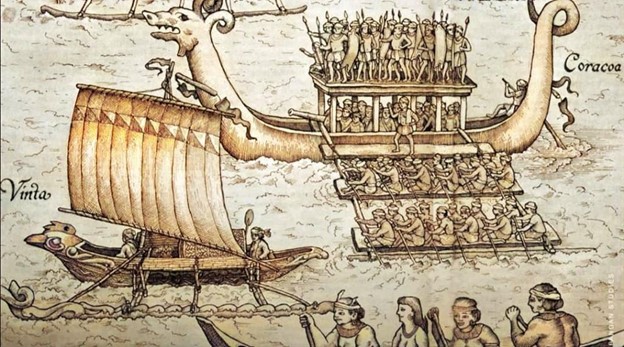

When, by 1599, the Spanish contingent had to withdraw from the area altogether owing to the lack of funds and supplies, it was with Buayan that Sulu joined in a confederacy which fitted out a fleet of fifty vintas bearing over three thousand well-armed warriors. Under the leadership of the “Pilots of the Mindanao River,” Sali and Sirongan, the join fleets headed north to ravage Oton and Panay Islands.

Hurley, Vic. 1936. Swiss of the Kris: The Story of the Moro. Original Publication. E. P. Dutton & Co. Inc. Filipiniana Reprint Series. 1985 Cacho Hermanos, Inc.

Morga, Antonio de. Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas. Jose Rizal, ed., 1890 (first published in Mexico, 1609). Translated into English (Rizal ed.) by Encarnacion Alzona, Manila, 1962.

Read More

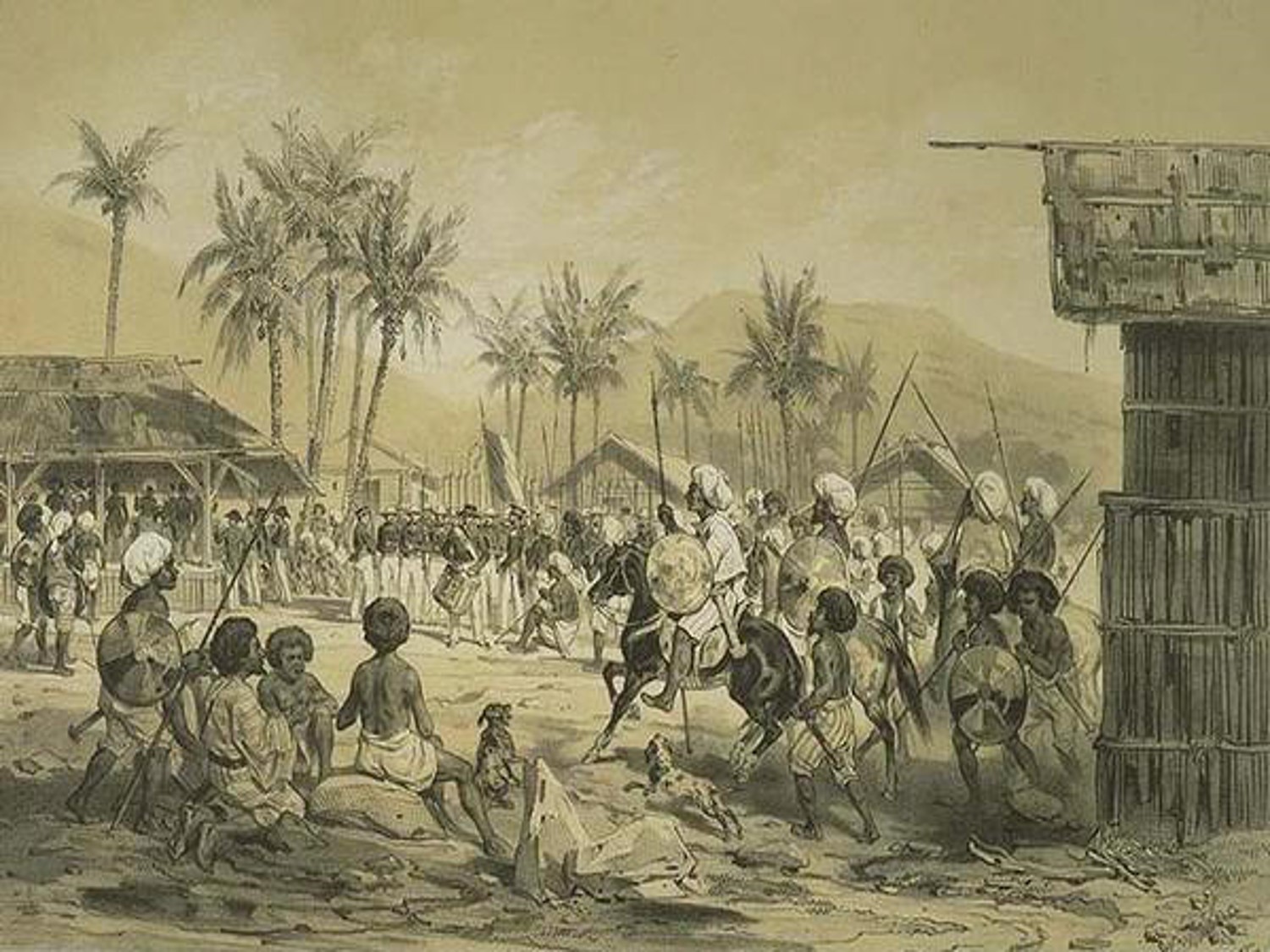

Sultanato ng Maguindanao at Pat a Pongampong ng Ranao

1600 - 1900

Sultanato ng Maguindanao at Pat a Pongampong ng Ranao from 1600 - 1900

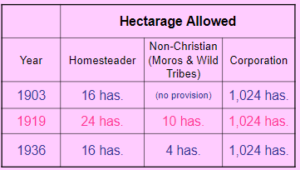

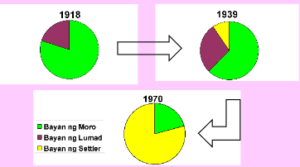

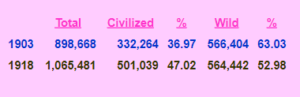

“In the fullness of its glory, the sultan of Maguindanao ruled over the whole southern coast of Mindanao from Point Tugubum (Tagum?), east of Mati, to Zamboanga, and beyond this latter point to the outskirts of Dapitan. All the pagan tribes living around the Gulf of Davao and in the Sarangani country, and all the Subanos west of Tukuran and Dapitan submitted to his power and paid him tribute. In the Upper Rio Grande Valley the power of the rajas of Bwayan was felt and respected as far as the watershed of the Cagayan Valley on the north and the...“In the fullness of its glory, the sultan of Maguindanao ruled over the whole southern coast of Mindanao from Point Tugubum (Tagum?), east of Mati, to Zamboanga, and beyond this latter point to the outskirts of Dapitan. All the pagan tribes living around the Gulf of Davao and in the Sarangani country, and all the Subanos west of Tukuran and Dapitan submitted to his power and paid him tribute. In the Upper Rio Grande Valley the power of the rajas of Bwayan was felt and respected as far as the watershed of the Cagayan Valley on the north and the inaccessible slopes of Mount Apo on the east. The Ranao Moros control the whole country and the seacoast west of Cagayan de Misamis and north of the Illana Bay.”